Pinpointing cancer earlier and faster

In 2020, an estimated 1.8 million new cases of cancer were diagnosed in the United States, according to the National Cancer Institute. In Michigan, that number was estimated at nearly 62,000.

Thanks to the advanced technology of the PET/CT scanner, doctors can now see exactly where cancer is located in the body by combining two already-established methods. Positron emission tomography, or PET, uses a radioactive tracer that is injected into the body to identify cancer. Once the cancer is found, the tracer binds to the cancer cells and emits a signal detected by the PET scanner. The second method is computerized tomography, or CT imaging technology, which reveals a detailed image of anywhere cancer is present, whether it is on the lungs or inside a bone, for example.

Mark DeLano, professor and chair of Radiology at the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine

“We call it hybrid technology when you mix two different kinds of imaging together and you get new insights,” says Mark DeLano, a professor and chair of the Department of Radiology in the MSU College of Human Medicine, who uses this technology to guide the treatment of cancer patients. “A PET scan pinpoints the tumor markers inside your body such as specific proteins on cancer cells or how much energy the tumor is using, and the CT scanner looks more at your structure, such as bones, organs and blood vessels.”

This makes the total-body PET/CT scanner technology the ideal tool to diagnose and guide the treatment of cancer. Until now, this technology had only been used in the U.S. for research purposes.

The pinpoint accuracy — and speed — of the technology are a major benefit to patients. A typical head-to-toe PET scan takes about 40 minutes to complete. For patients who are already anxious or uncomfortable, this can feel like an eternity, and to hold still that long is even more of a challenge for children or for individuals with claustrophobia or other conditions. When a patient moves during the scan, it greatly reduces both the accuracy of the stitching process used to create a cohesive image and the quality of the final image. This can profoundly impact the ability to detect small tumors. The new scanner eliminates both issues.

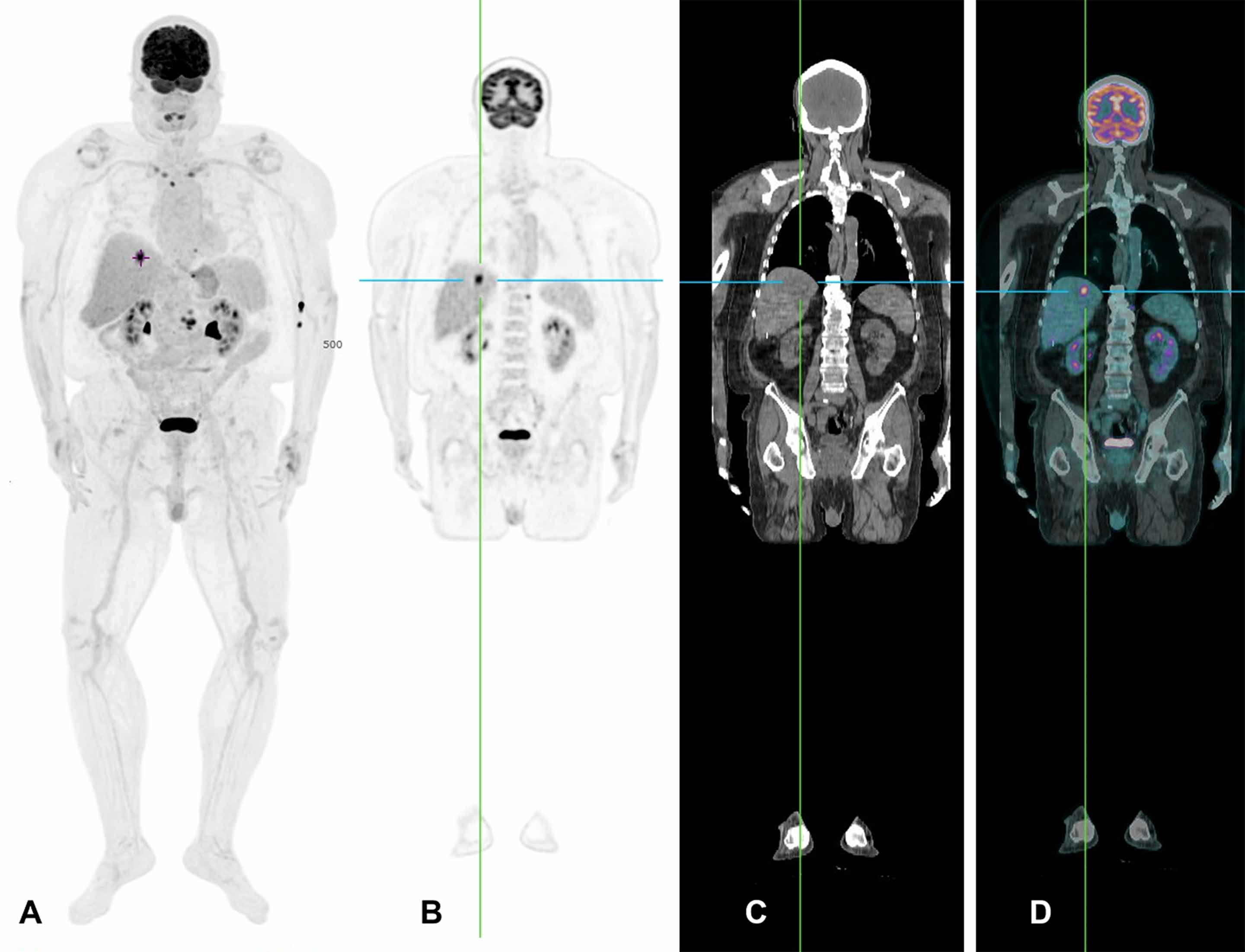

Patient undergoing a total-body PET/CT scan. A: Maximum intensity projection, which is a 3D reconstructed image from the PET/CT imaging.B: PET imageC: CT imageD: PET/CT fused together. Image courtesy of BAMF Health

“With this cutting-edge total-body PET/CT scanner, we can finish the full-body scan in one minute and scan 194 centimeters (76 inches) at one time,” says Anthony Chang, founder and chief executive officer of BAMF Health. “That means it takes one-fortieth of the time.”

The entire patient is imaged in a single scan, which improves the final image quality and the detection of small tumors and lesions. By detecting cancer earlier, researchers can initiate more aggressive therapeutic options sooner and be more confident in reducing therapeutic intensity if there is no evidence of widespread disease.

“Conventional scanners can detect signs of cancer one centimeter (0.39 inches) in size, but this new scanner can detect signs of cancer less than two millimeters (less than one-tenth of an inch) in size,” says Chang.