“Ask the expert” articles provide information and insights from MSU scientists, researchers and scholars about national and global issues, complex research and general-interest subjects based on their areas of academic expertise and study. They may feature historical information, background, research findings or offer tips.

Michigan State University researcher Morteza Mahmoudi studies factors impeding the development of very promising and extremely tiny diagnostics and therapeutics known as nanomedicines.

One of those factors is a lack of standards when it comes to how these medicines are analyzed and characterized in the laboratory. Mahmoudi was part of a team that recently revealed a shocking level of disagreement between lab results that researchers rely on as they create and test new nanomedicines. That team included Ali Ashkarran at MSU and collaborators at the University of California, Berkeley and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

Mahmoudi, an assistant professor in MSU’s Department of Radiology, explains why addressing such disagreements with stronger standards will help ensure future nanomedicines are safe, effective and successful.

The following answers are excerpts and adaptations from an article originally published in The Conversation.

What are nanomedicines?

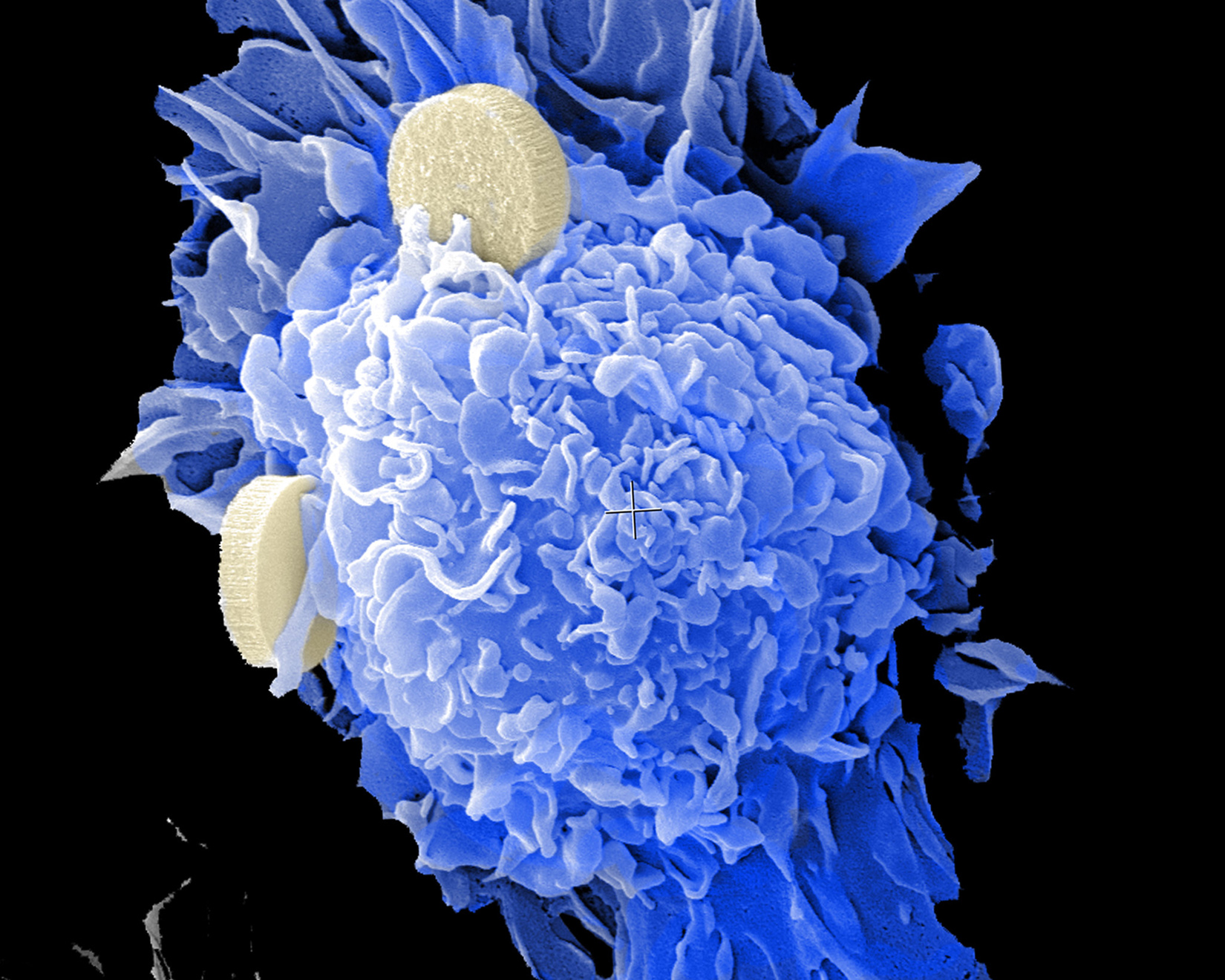

Nanomedicines took the spotlight during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers are using these very small and intricate materials to develop diagnostic tests and treatments. Nanomedicines are already used for various diseases, such as the COVID-19 vaccines and therapies for cardiovascular disease. The “nano” refers to the use of particles that are only a few hundred nanometers in size, which is significantly smaller than the width of a human hair.

If we’re already using nanomedicines, why is there a need to develop and implement new standards for how we study them?

Although there are success stories in the field, many scientists — including myself — believe there aren’t enough, especially considering the amount of effort and taxpayer money we’ve invested in nanomedicine development.

To that end, researchers have been working to improve the safety and efficacy of nanomedicine through various approaches. These include modifying study protocols, methodologies and analytical techniques to standardize the field and improve the reliability of nanomedicine data.

Aligned with these efforts, my team and I have identified several critical but often overlooked factors that can influence the performance of a nanomedicine, such as a person’s sex, prior medical conditions and disease type.

Taking these factors into account when designing studies and interpreting results could enable researchers to produce more reliable and accurate data and lead to better nanomedicine treatments.

Can you give an example of how?

Nanomedicines, just like all medications, are surrounded by proteins from the body once they come into contact with the bloodstream. This protein coating, known as a protein corona, gives nanoparticles a biological identity. This biological identity determines how the body will recognize and interact with the particles, like how the immune system has specific reactions against certain pathogens and allergens.

Knowing the precise type, amount and configuration of the proteins and other biomolecules attached to the surface of nanomedicines is critical to determine safe and effective dosages for treatments.

However, one of the few available approaches to analyze the composition of protein coronas requires instruments that many nanomedicine laboratories lack. So these labs typically send their samples to separate proteomics facilities to do the analysis for them. Unfortunately, many facilities use different sample preparation methods and instruments, which can lead to differences in results.

Those are the types of differences you investigated in your team’s new study. What did you find?

We wanted to test how consistently these proteomics facilities analyzed protein corona samples. To do this, my colleagues and I sent biologically identical protein coronas to 17 different labs in the U.S. for analysis.

We had striking results: Less than 2% of the proteins the labs identified were the same.

Our results reveal an extreme lack of consistency in the analyses researchers use to understand how nanomedicines work in the body. This may pose a significant challenge not only to ensuring the accuracy of diagnostics, but also the effectiveness and safety of treatments based on nanomedicines.