Michigan State University researcher Acer VanWallendael understands the public’s fascination with fungus. It is, after all, a fungus that kicks off the zombie apocalypse in the hit HBO series “The Last of Us.”

Thankfully, no known fungus has the power to turn people into monsters and upend society. But VanWallendael, a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of Plant Biology, is helping highlight the very real and diverse ways microscopic fungi affect crops.

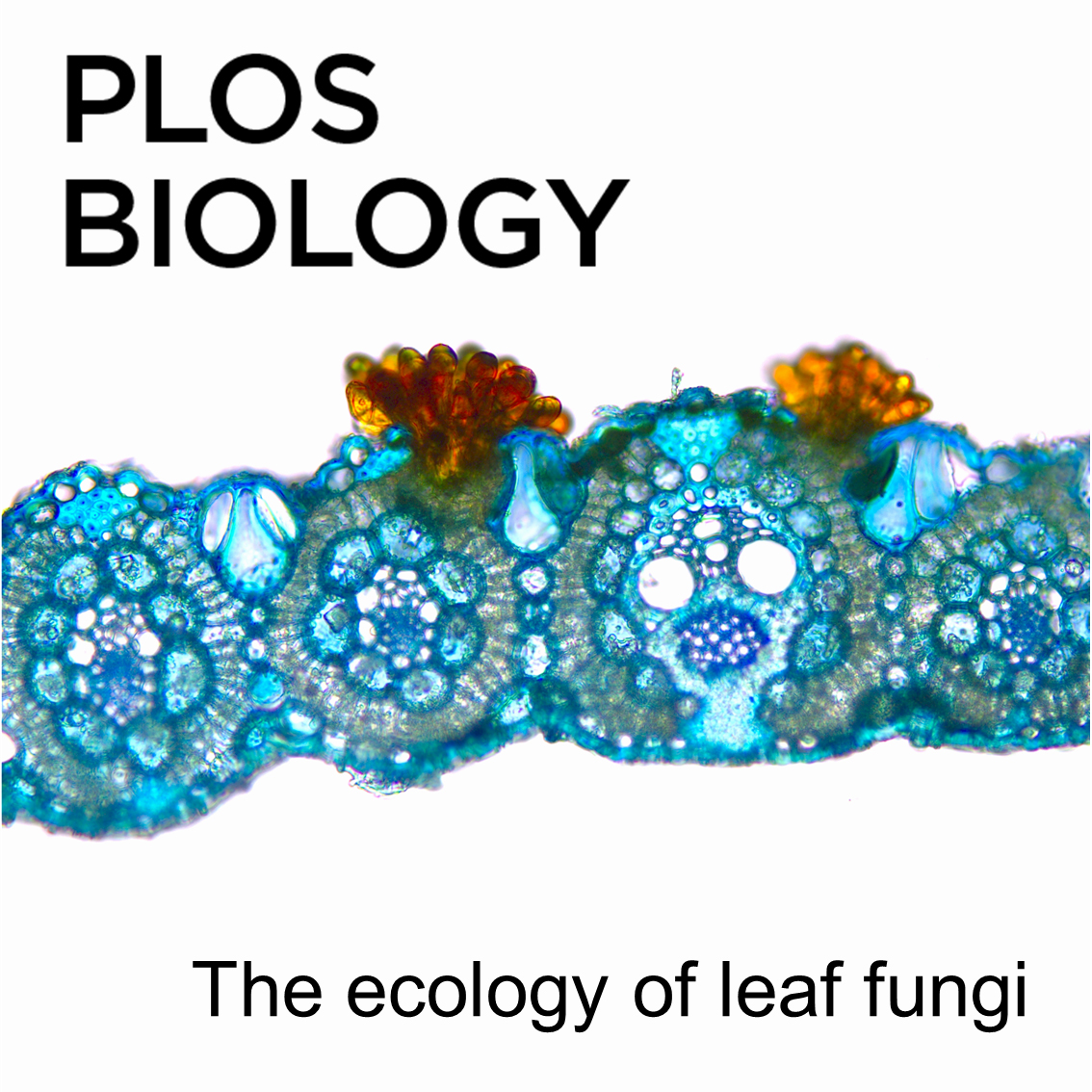

More specifically, his team’s recent paper in the journal PLOS Biology explored the complex relationships fungi have with switchgrass, a promising biofuel crop.

“One of the reasons we’re so interested in switchgrass is it’s a perennial crop,” said VanWallendael, who works with the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center. “Unlike an annual crop like corn, switchgrass will put down deep roots so it can come back year after year while holding soil in place and storing carbon.

“But one of the downsides is that pathogens can also build up where the grass is growing over time,” he said. “Perenniality might put the plant in conflict with disease.”

In the case of a biofuel candidate like switchgrass, fungal pathogens can both diminish the health of the plant and the quality of fuel made from it, VanWallendael said. At the same time, however, there are fungi that help the plant.

For example, there are fungi known as hyperparasites that attack fungal pathogens. Others release chemicals that make the grass taste gross to grazing cattle and bison. There are even fungi in the Entomophaga genus that infect grasshoppers that eat the grass.

Like Cordyceps, the fungus featured in “The Last of Us,” Entomophaga alters the behavior of its hosts. The infected grasshoppers will stop eating the switchgrass and start basking in the sun to induce a fungus-killing fever. If the fever fails, however, the basking position becomes a perfect launching point for the spores that grow from fuzzy fungal hyphae, or tubular projections, sprouting from cracks in the insect’s carapace.

That’s right. Mind-controlling fungi are real, but don’t worry, they’re working on the side of the plants. And, again, they definitely don’t turn humans into zombies (insects aren’t so lucky, though).

Back on the switchgrass field, thousands of species of microscopic fungi can be present, with hundreds on a single switchgrass leaf that change over time. On top of that, the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center is studying several different varieties of switchgrass.

VanWallendael and his colleagues are showing which combinations result in the most robust, resilient grass as well as how plants with certain gene variants can control the fungi colonizing them. The team is looking to provide information that will help researchers grow the healthiest switchgrass for biofuel and help remediate damaging fungal infections.

They also hope their work will help remind folks that these fungi play an outsize part in shaping our world, even if it isn’t quite as dramatic as we see on TV.

“It’s easy to forget about microscopic fungi. There’s the yeast in our bread and in our beer, but we tend to ignore them in the wild,” VanWallendael said. “I hope this helps people remember that there are whole communities of fungi in a single leaf doing really interesting things that are important to the success and failure of the plant.”

VanWallendael is a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of David Lowry, an associate professor in the College of Natural Science. The team’s work was also supported by the National Science Foundation Long-term Ecological Research Program at the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station and by Michigan State University AgBioResearch.