While vacationing crowds head to Michigan’s beaches, lakes and cities, for many Spartan scientists, the summer months are ripe for research in the field. As one of the nation’s top research universities, Michigan State University prepares students, faculty and staff to think critically and creatively to gather important data that will help shape future conservation methods and inform public health measures across the state.

While vacationing crowds head to Michigan’s beaches, lakes and cities, for many Spartan scientists, the summer months are ripe for research in the field. As one of the nation’s top research universities, Michigan State University prepares students, faculty and staff to think critically and creatively to gather important data that will help shape future conservation methods and inform public health measures across the state.

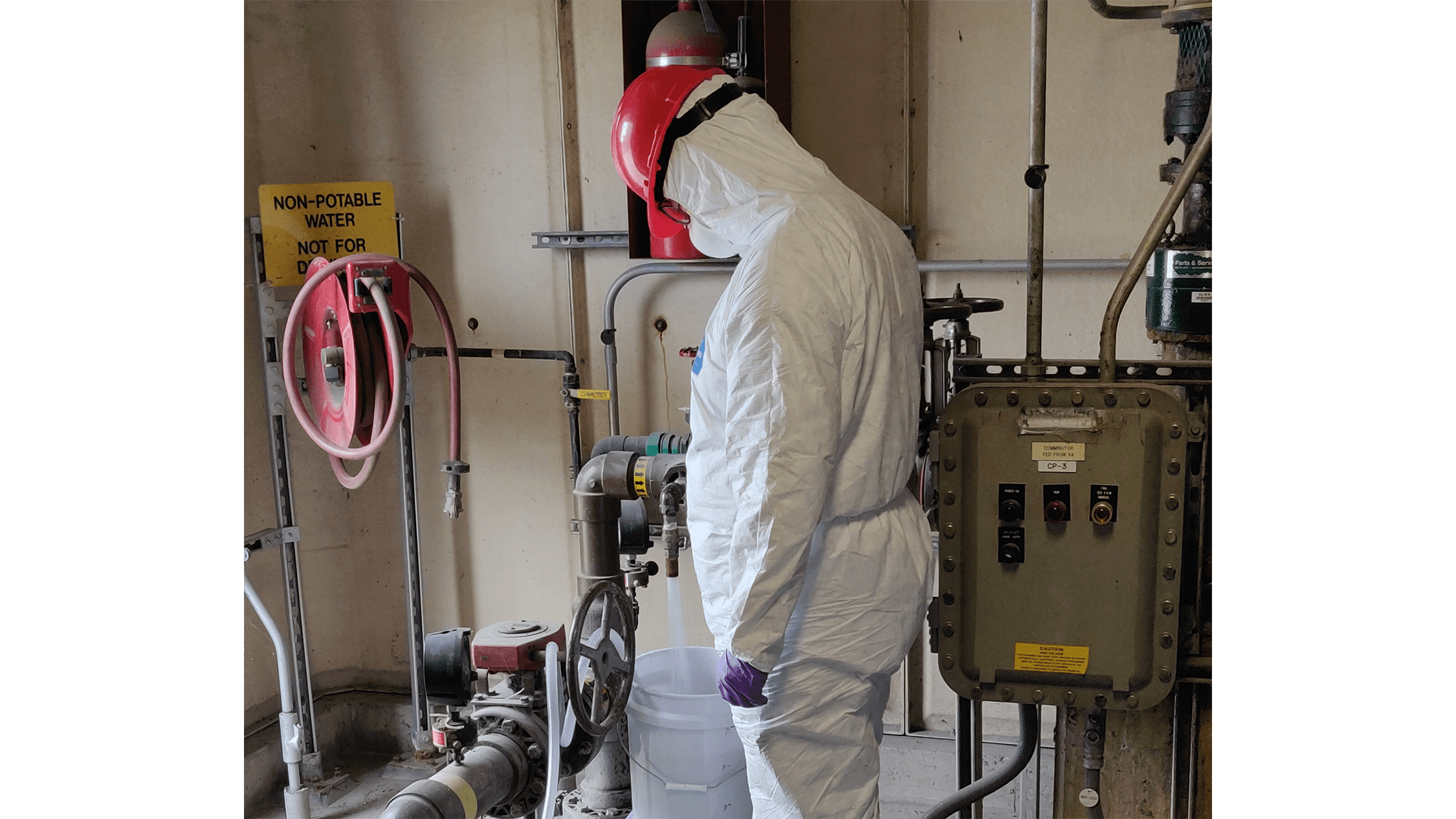

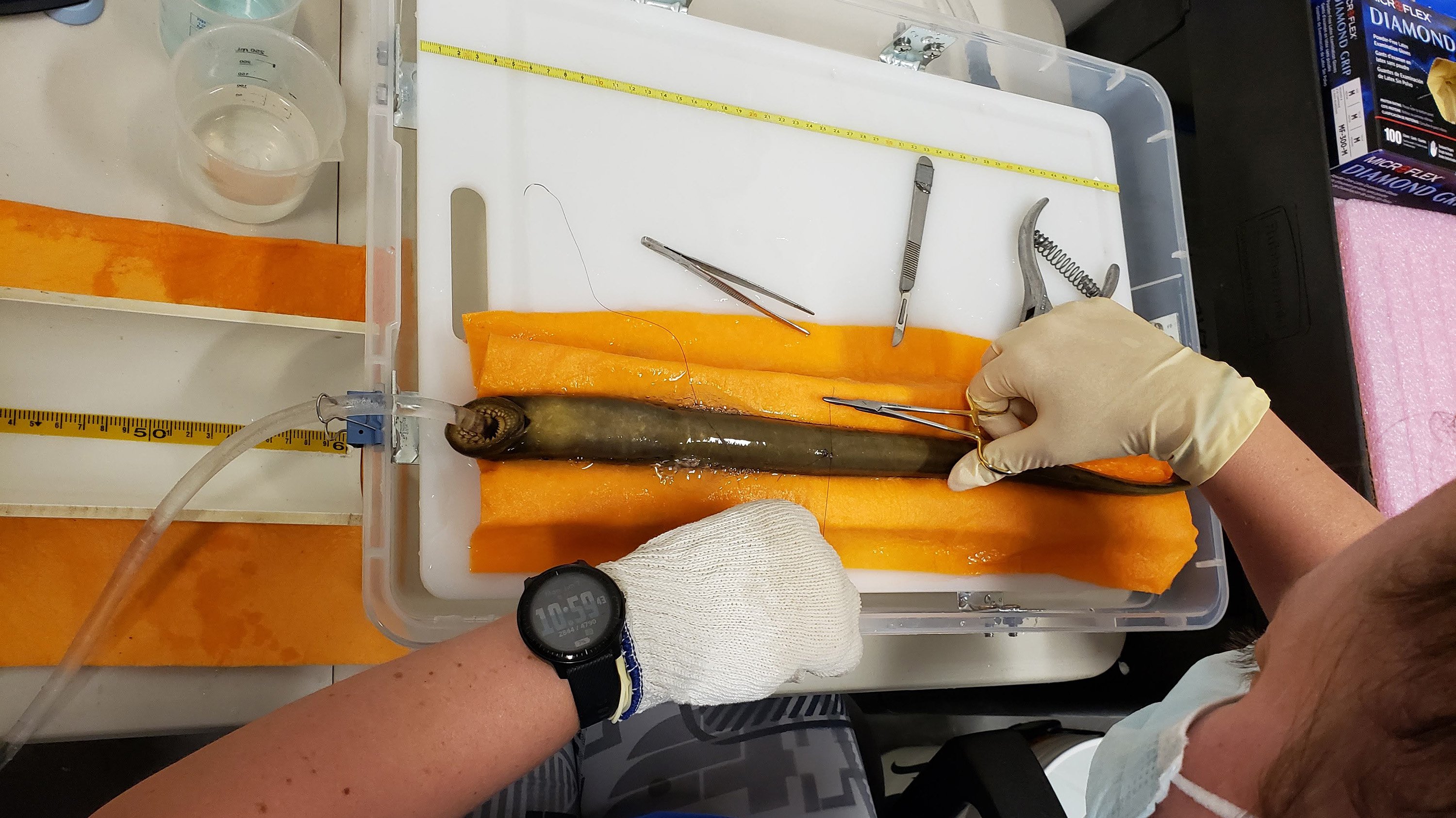

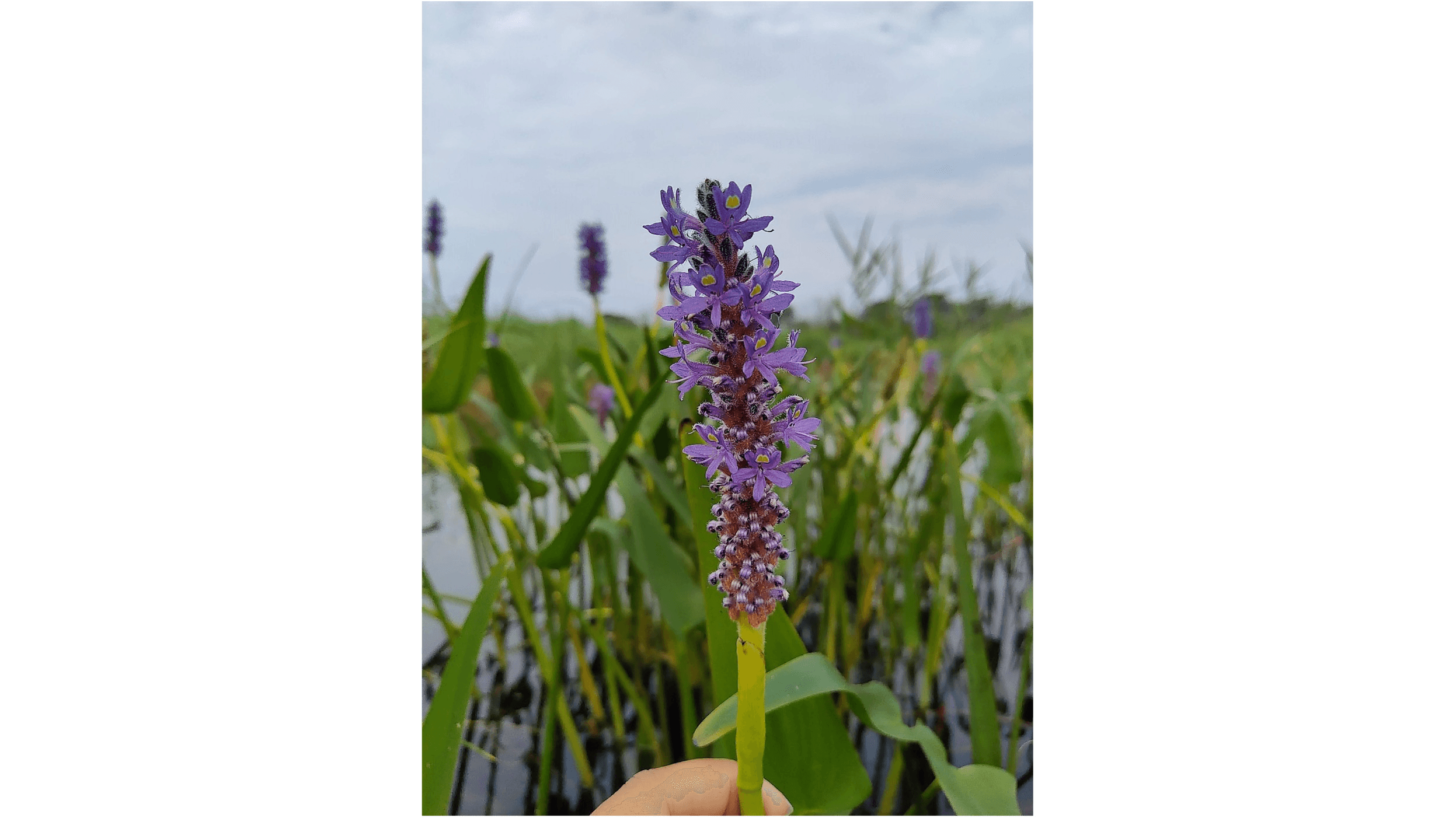

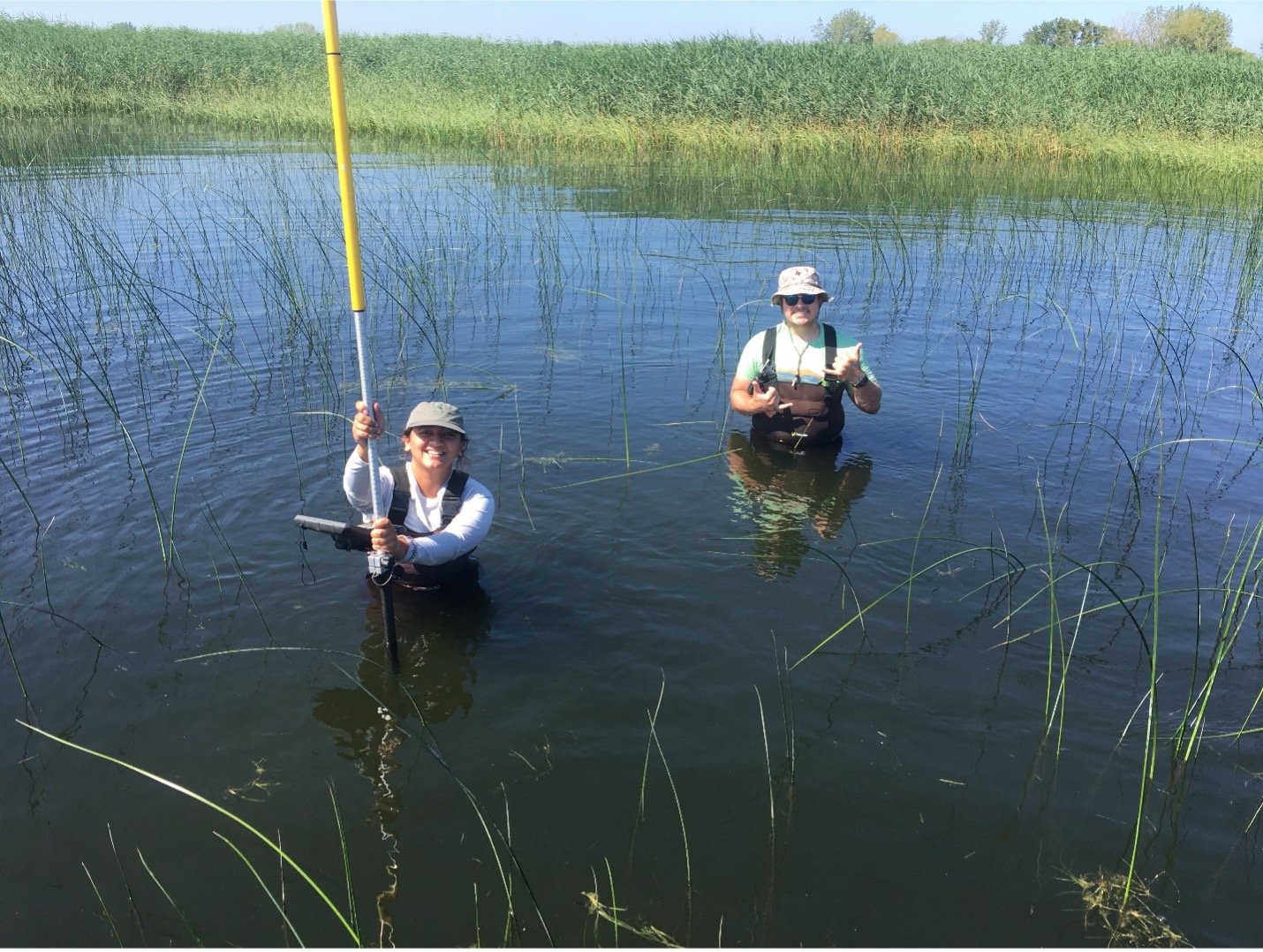

These intrepid researchers can be found drilling into steel frames from 10 feet above, navigating municipal wastewater, tracking invasive species in kayaks and mapping coastal erosion along the Great Lakes.

The following photo galleries chronicle some of the important research projects Spartans took part in this summer.

Creating drought conditions

For more than 30 years, W.K. Kellogg Biological Station, located between Kalamazoo and Battle Creek, has been part of the national Long-Term Ecological Research network, where MSU researchers have studied the effects of land use intensity in agricultural landscapes on yield, soil health, food webs and more.

Led by MSU professor and principal investigator Nick Haddad, the MSU Kellogg Biological Research Station’s Long-Term Ecological Research team has discovered that no-till agriculture increases soil health and reduces greenhouse gas emissions, all while increasing agricultural yield. This summer, the team embarked upon a new experiment to find out how resilient different land uses are in response to growing-season drought.

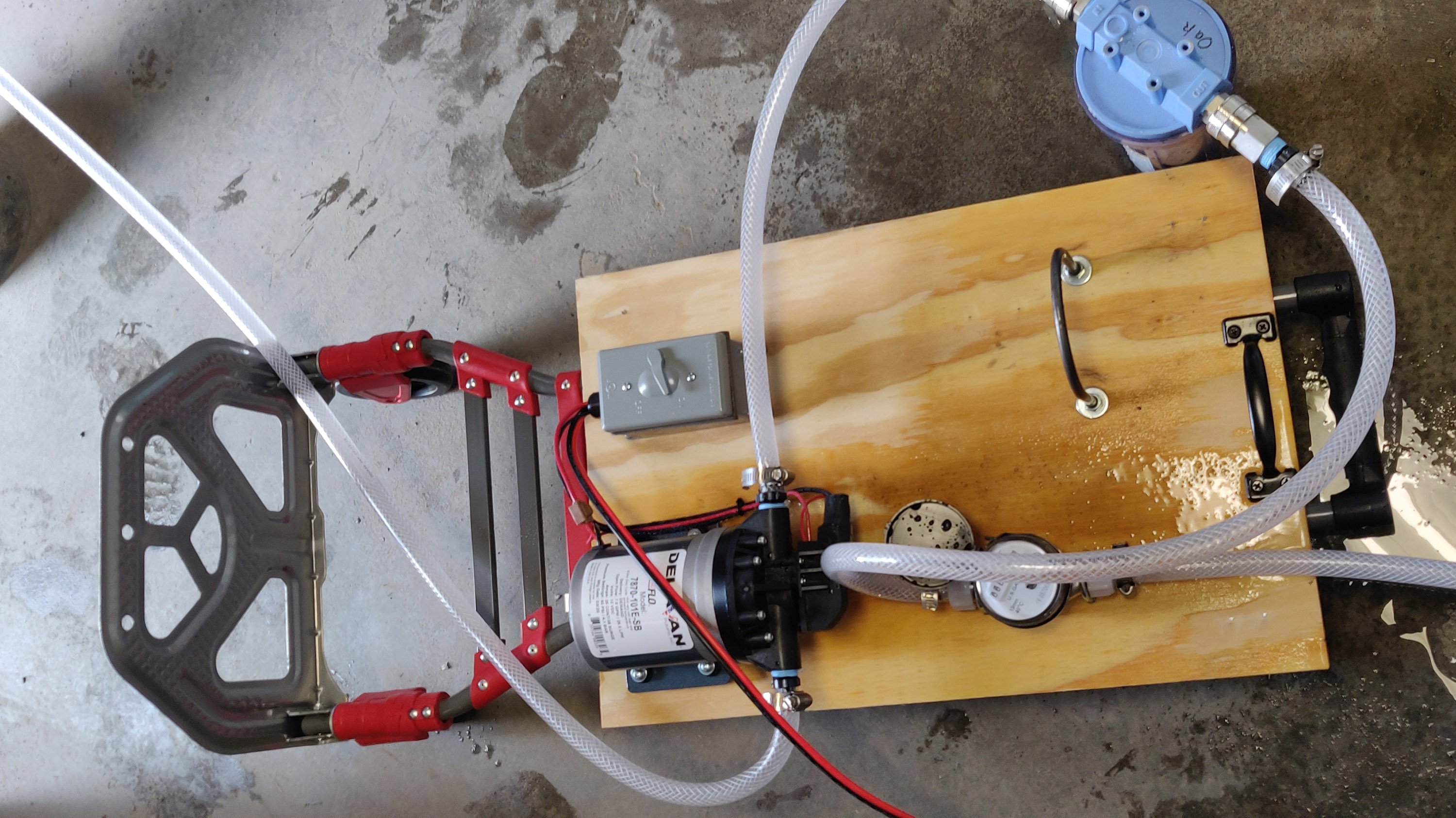

Since drought-like conditions do not happen on command, KBS faculty, staff and students rolled up their sleeves to construct rainout shelters, which are, as the name suggests, shelters that prevent rain from hitting the ground.

As Haddad put it, the experiment provides “one of the best snapshots in the 33-year experiment.”

Constructing rain shelters, as it turns out, is super labor-intensive. Nameer Baker, science coordinator, shares what the experience was like in his Faculty voice: Keeping the rain out.