Writing is hard.

Not just for award-winning authors attempting another bestseller or doctoral students preparing their dissertations—but for everyone. Especially children who are just learning how to turn their thoughts into sentences and express them on a blank page.

The art—and science—of teaching how to write is equally complex. Informational writing becomes more integrated into standard curriculum in fourth grade where the average class ranges between 25 to 30 students, and each of them has varying degrees of experience when it comes to writing.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, written communication is important in over 90% of occupations—from entry-level jobs to high-level management. This necessitates preparing students for real-world writing demands that will follow them throughout their schooling and into their careers.

Adrea Truckenmiller, associate professor in MSU’s College of Education, has been researching written communication in elementary school settings for more than a decade. Her focus has been on identifying the most teachable components of reading and writing achievement, creating assessments to better understand student strengths and weaknesses, and observing elementary schools’ processes for implementing evidence-based instruction in classrooms.

Through her research, she found that most curricula don’t include impactful writing instructional strategies. Instead, writing has been viewed as an “add-on” layered on top of other subjects.

“One aspect that contributes to this wide range of writing development amongst students is that most curricula don’t [include] good writing instructional strategies and teachers aren’t trained in pre-service training programs,” Truckenmiller said. “They get some training but not enough to make them feel confident in their effectiveness to teach writing. Teachers were vulnerable with us about not knowing what to do or where to start.”

The Writing Architect

Recognizing the difficulty of learning how to write for students and the limited instructional materials for teachers, Truckenmiller developed a tool called the Writing Architect (WA) with a grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

“Writing is complex,” Truckenmiller said. “The WA is cracking a code to a problem we’ve been wrestling with for a really long time, which is ‘how do we figure out where kids are in their development of writing and move forward.’”

The WA is a web-based platform that provides students with a writing assessment and typing fluency test to determine individual strengths and weaknesses. Based on student scores, teachers are then equipped with evidence-based instructional material that Truckenmiller’s team has compiled in a repository with the most impactful teaching practices tailored to individual students’ needs.

“We conducted a ton of research throughout three studies to figure out the best places to start for teaching,” Truckenmiller said. “Based on our research, we found five high-leverage components.”

The five components are text structure, vocabulary use, spelling, sentence accuracy, and typing fluency.

“Identifying these five components was a major finding,” Truckenmiller said. “This is the first classroom-based assessment to predict a majority of students’ performance on the M-STEP (end-of-year test of grade-level expectations).”

How Does It Work?

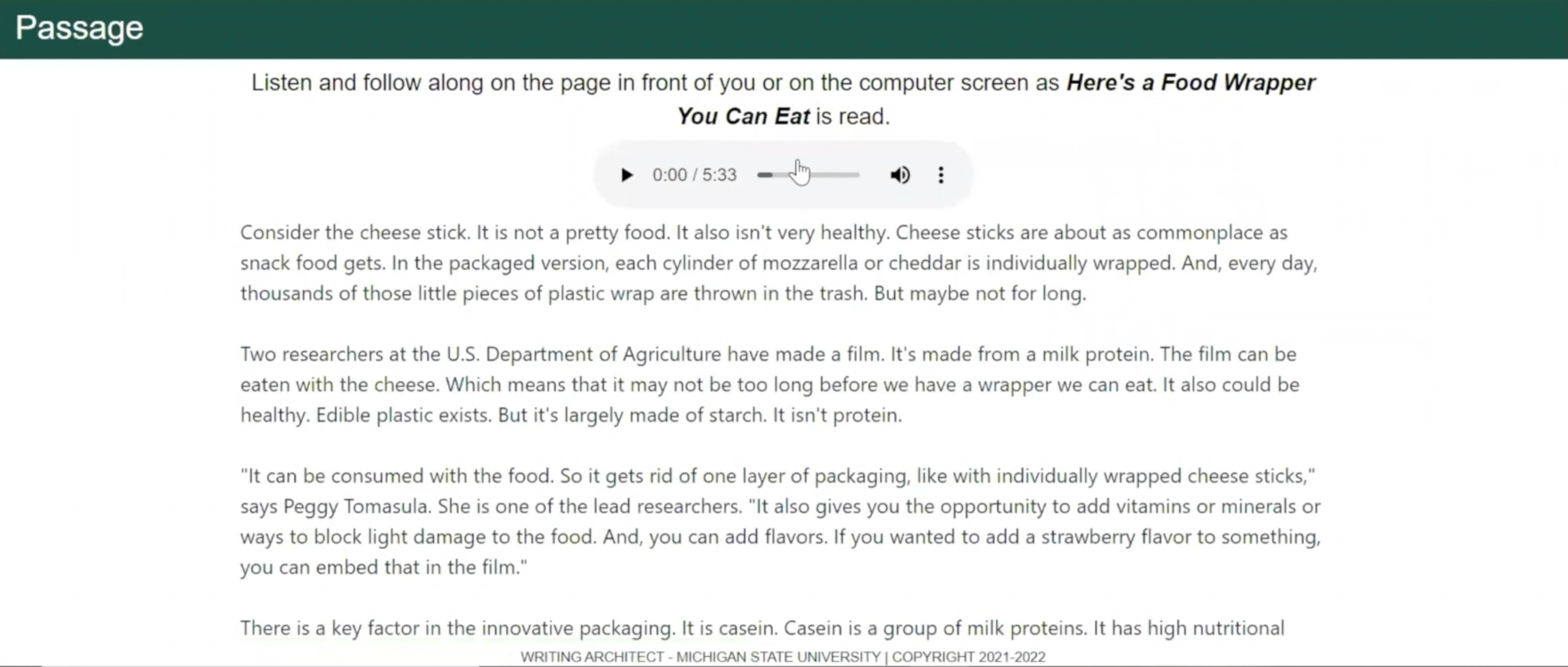

Students log into the web application on their computers and are instructed to listen to an informational passage rather than read a question, ensuring their reading abilities do not interfere with outcomes. Next, they are allotted 15 minutes to write their response to the prompt. Following the writing assessment, students complete a 90-second typing fluency check, which helps assess their transcription skills. The combination of these two components provides educators with a comprehensive overview of a student's writing proficiency, enabling them to tailor instruction to individual needs.

After both assessments are complete, the WA web application automatically scores some components and facilitates other scores for the research team. Once scored, teachers are hyperlinked to different types of instructional material to assist students in the development of their writing.

The student scores correlate with the five elements of instruction Truckenmiller identified. With this knowledge, teachers can easily form small groups of students who have similar skill levels and provide appropriate instruction to help them succeed.

Following the implementation of instructional material, the students participate in a second writing assessment using a different prompt to determine whether their skills improved between pre- and post-testing.

In the Classroom

In 2021, Truckenmiller and her team recruited schools from several intermediate school districts (ISDs) to participate in the WA pilot program. Prior to entering classrooms, teachers, reading and writing coaches, and principals alike participated in a professional learning community where they were introduced to theories behind writing development and oriented on the WA tool.

Megan Perreault was involved in the initial pilot of the WA after meeting Truckenmiller in 2017 while serving as a curriculum and instruction consultant for special education with the Muskegon ISD. Recognizing a common need, Perreault connected the research team with elementary classrooms across Muskegon.

“The pieces that seemed to be missing from curriculum are the pieces that the Writing Architect is providing,” she said. “That’s what is really powerful about the tool—it helps teachers make classroom-level decisions to meet the needs of their students. There’s a lot of power in bridging that theory to practice.”

Cherish Sarmiento, now an assistant professor at Utah State University, studied under Truckenmiller while completing her doctorate at MSU. She conducted the research that identified how best to measure and teach vocabulary. She also spent time in classrooms that were utilizing the WA over a three-month period to observe the tool in practice and score assessments.

“Writing in general is really hard to teach, plus it can be time-consuming,” Sarmiento said. “We wanted to make writing more accessible for teachers to implement in a short time period while also producing some indicators of students’ writing abilities, so teachers can get actionable insights.”

Throughout her observations, Sarmiento said she and her fellow researchers learned a lot about instructional techniques. The teachers they worked with all agreed that having a tool was really helpful to implement writing techniques, and they were grateful to have the supports and resources the WA provided.

Participating in WA not only measured students’ writing ability but provided insights into their feelings about writing.

“Some students like writing, so being asked to write for 15 minutes on a computer isn’t scary whatsoever, but other students experience writing anxiety,” she said. “The first time taking the test, students don’t know what to expect, and it can be overwhelming, but the second time students were much more fluent in understanding the process ... and no tears were shed.”

What’s Next

The WA pilot is entering its fifth year. With each phase of modification, the WA has evolved based on teacher input, researchers’ observations, and the need to improve students’ self-efficacy. This year, the research team will continue to analyze the data they collected from a randomized controlled trial in 2023-24 to examine potential impacts of the WA on teacher and student outcomes with roughly 40 teachers and 800 students.

Truckenmiller and her team are also working to adapt instructional recommendations to provide stronger and more action-oriented resources for teachers, while advocating for an increase in teacher support for writing curriculum and the implementation of writing routines.

To address student confidence, the team is leaning on an evidence-based practice called the Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) to help students develop self-regulation skills, like motivation and self-belief, embedded within explicit instruction in text structure.

Truckenmiller is looking forward to continuing to modify the WA with the help of her students at MSU, and the input from students and teachers at participating schools across the state to connect evidence-based writing practices with student needs.

“Research in writing requires working with a team and engaging with multiple perspectives,” she said. “Research means nothing if it can’t be done in practice, and practice needs to inform what we do in research. That’s really at the heart of what we do.”

The study will continue throughout 2026.

This story originally featured on the Engaged Scholar website.