Leonardo da Vinci once said, “We know more about the movement of celestial bodies than about the soil underfoot.”

James Tiedje, a world-renowned expert in microbiology at Michigan State University, agrees with da Vinci. But he aims to change this through his work on the Critical Zone, part of the dynamic “living skin” of the Earth.

“The Critical Zone extends from the tops of trees down through the soil to depths up to 700 feet,” Tiedje said. “This zone supports most life on the planet as it regulates essential processes like soil formation, water cycling and nutrient cycling, which are vital for food production, water quality and ecosystem health. Despite its importance, the deep Critical Zone is a new frontier because it’s a major part of the Earth that is relatively unexplored.”

What researchers found in the deep layers of the Critical Zone

Tiedje, a University Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the MSU Department of Microbiology, Genetics and Immunology and the Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences, discovered in this huge, unexplored microbial world a completely different phylum, or primary category, of microbe called CSP1-3. This new phylum was identified in soil samples from both Iowa and China at depths down to 70 feet. Why Iowa and China? Because these two areas have very deep and similar soils and we want to know if their occurrence is more general and not just in one area, Tiedje said.

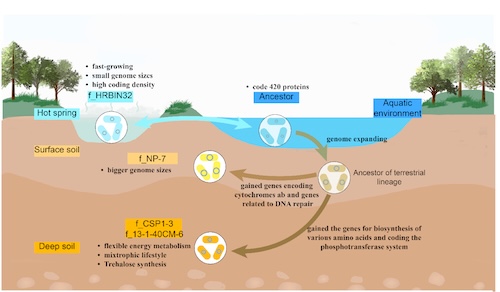

Tiedje’s team extracted DNA from these deep soils and found that CSP1-3’s ancestors lived in the water — hot springs and fresh water — many millions of years ago. They underwent at least one major habitat transition to colonize soil environments — first topsoil and, later, deep soils, during its evolutionary history.

Tiedje also found that the microbes were active. “Most people would think that these organisms are just like spores or dormant,” he said. “But one of our key findings we found through examining their DNA is that these microbes are active and slowly growing.”

Tiedje also was surprised to find these microbes were not rare members of the community, but were dominant; in some cases they made up 50% or more of the community, which is never the case in surface soils.

“I believe this occurred because the deep soil is such a different environment, and this group of organisms has evolved over a long period of time to adapt to this impoverished soil environment,” Tiedje added.

How the microbes purify water

Soil is our planet’s biggest water filter. When water passes through soil, it is cleaned through physical, chemical and biological processes. The surface soil, where most plant roots reside is often a very small volume of soil through which rainwater passes quickly. But the deep soil has a much larger volume. This is where CSP1-3 helps out. They live off the carbon and nitrogen that’s washed down from the topsoil to complete the purification process.

“CSP1-3 are the scavengers cleaning up what got through the surface layer of soil,” Tiedje said. “They have a job to do.”

What’s next?

The next step, Tiedje said, is to culture some of these microbes in the laboratory and if they grow, we can then learn more about their unique physiologies that allow them to be so successful in this deep soil environment. This is not easy. Most of the microbial world is not cultured because it’s so difficult to replicate the conditions in which they live and grow.

For example, since CSP1-3’s ancestors lived in hot springs, Tiedje’s lab is trying to grow them at high temperatures as one example of testing new growth conditions based on information from their genomes.

But if anyone can do it, Tiedje can, since he also discovered microbes that can dechlorinate chlorinated compounds.

“CSP1-3’s physiology, driven by their biochemistry is different, so there may be some interesting genes of value for other purposes,” he said. “For example, we don’t know their capacities for metabolizing tough pollutants and, if we could learn that, we can help solve one of the Earth’s most pressing problems.”

The paper, Diversification, niche adaptation and evolution of a candidate phylum thriving in the deep Critical Zone, was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.