Italy’s Phlegraean Fields is a hotspot of volcanic activity — an ever-shifting landscape pocketed with acidic hot springs. This huge caldera is a part of the Campanian volcanic arc, which includes Mount Vesuvius, whose eruption wiped out the Roman city of Pompeii in 79 C.E. Yet, despite the hostile and scalding conditions of this environment, some microorganisms thrive. And researchers at Michigan State University are taking notice, hoping to uncover new information about how a particular alga survives in such extreme conditions.

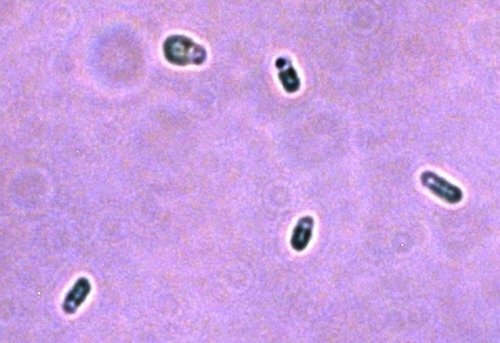

In a new paper published in Plant Physiology, researchers in the MSU-DOE Plant Research Laboratory and the Walker lab — in collaboration with the Shachar-Hill lab of the Department of Plant Biology — are studying Cyanidioschyzon merolae, or C. merolae, and its unique ability to photosynthesize its own food in an environment that would make this impossible for other organisms. Understanding how C. merolae operates in such extreme conditions can help scientists better extrapolate — or improve upon — the process of photosynthesis, a function vital to all life on Earth.

“Science has only described a narrow slice of how nature has dealt with the same challenges, but in different ways,” said Berkley Walker, the principal investigator for this study. The paper “did a great job of determining that the way we commonly see something being done is not the way it has to be done.”

This study looks at the carbon-concentrating mechanism, or CCM, in C. merolae. Many photosynthetic organisms use a CCM to boost the efficiency of photosynthesis. The CCM acts as a delivery driver, taking carbon dioxide and placing it where it can be best utilized.

At present, the CCM is well understood in plants, but only well characterized for a handful of algae species.

“C. merolae is a very simple organism, so it doesn’t have all the structures and abilities that people typically associate with how a carbon-concentrating mechanism works,” said Anne Steensma, graduate student in the Department of Plant Biology and the Molecular Plant Sciences graduate program. She is a co-first author of this study. “Our paper gets at what the . . . basic features that you need to build a carbon-concentrating mechanism are.”

Working with collaborators from the MSU Department of Statistics and Probability, the researchers devised mathematical models to simulate C. merolae. A lot of effort went into devising and refining this model of the algae so researchers can continue to use it in further studies.

“A big challenge in this study was figuring out how to make sense of how the many different parameters we were plugging into our model worked to interact with each other,” said Joshua Kaste, a co-first author on this paper alongside Steensma. “This made our collaboration with Dr. Chih-Li Sung and Junoh Heo in the statistics department vitally important.”

To create this model, the researchers input data that would allow the model to act as a C. merolae cell would in real life, or as close to it as possible. It’s a bit like giving an actor a script: You know the words the actor will say, but not every detail of their performance. The components of the CCM that the researchers best understand is the script, coding the computer to create a model of the mechanism to as much accuracy as possible.

Having this model allows the researchers to input new conditions to see how the algae might respond. For example, they can remove parts of the model and see if it breaks the function of the CCM. This can help researchers narrow which parts of the algae are vital to the CCM.

“This shows us the ‘minimal path forward’ for engineering a carbon-concentrating mechanism,” said Walker, who also serves as an associate professor in the PRL and the Department of Plant Biology. “The other way to look at it is that maybe we can improve this simple carbon-concentrating system in C. merolae and achieve even greater growth under the extreme environments that it lives under.”

This research was funded from the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the United States Department of Energy (DOE) (grant number DE-FG02-91ER20021). Additional funding came from the DOE (grant number DE-SC0018269), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation Research Traineeship Program and the National Science Foundation.