Ask the expert: Exploring the university’s civil rights legacy

Michigan State University has a storied civil rights legacy. It is home to the first African American president of any major U.S. university and one of the first integrated college football teams. According to 2021 data, MSU ranks in the top five among the American Association of Universities, the Big Ten and Michigan public universities in Black enrollment.

Pero Dagbovie, a University Distinguished Professor of history, the vice provost for graduate and postdoctoral studies, and the dean of the Graduate School at Michigan State, recently completed a book, “Forever in the Path: The Black Experience at Michigan State University,” published by Michigan State University Press. The book explores Black life at America’s first agricultural college from the 1890s through the late 20th century.

Here, Dagbovie discusses MSU’s early role in the modern Civil Rights Movement and the integration of institutions of higher education.

How has MSU’s Black student population grown since the Civil Rights Movement?

Integration at MSU did not happen suddenly. It was a gradual process with key turning points. It was the byproduct of Black students — and their allies — speaking out and actively protesting racial discrimination on campus and in East Lansing.

From 1904, when William Ora Thompson became the first known African American to graduate from the university, until the end of World War II, approximately 33 Black students graduated from MSU, including Myrtle Bessie Craig (Mowbray), who became MSU’s first African American woman to graduate in 1907. She was handed her diploma by President Theodore Roosevelt, the keynote speaker for the semicentennial graduation, and she went on to become an educator at historically Black colleges and universities.

A deliberate full-scale Black students-centered integration program at MSU began in the late 1960s. In 1967, approximately 700 Black students were enrolled at MSU. The number rose to about 1,000 in 1968, 1,500 in 1969, and 2,000 in 1970. By the early 1970s, during Clifton R. Wharton Jr.’s historic presidency, an average of about 2,500 Black students were enrolled at MSU.

During the 1980s, the MSU Black student population averaged about 2,500 per year, and by 1994, the Black student population rose to 3,000 for the first time. The total Black student enrollment in the fall of 2002 remains a record breaker at nearly 3,700.

What makes MSU a historical leader in the Civil Rights Movement?

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, MSU had more African American students than any university in the state, with the exception of Detroit’s Wayne State University. During that time, MSU’s Black student population was comparable to those at major urban universities.

For the last several decades, MSU has been considered the epitome of a major predominantly white university with a historical connection to the African American struggle for civil rights. What set MSU apart in the realm of civil rights was that former MSU president John Hannah was named chair of the Civil Rights Commission in 1957 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Serving presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, Hannah held that position until the late 1960s. During Hannah’s presidency, moreover, legendary football coach Duffy Daugherty, who led the Spartans from 1954 until 1972, built upon a tradition of integration on the gridiron launched by Biggie Munn when he was head football coach from 1947 until 1953.

MSU’s legacy as a civil rights supportive institution was solidified in 1970 when Clifton R. Wharton Jr. became the university’s 14th president, making him the first African American president of any major research one, or RI, institution in the United States.

What efforts did Black students undertake to champion equity at MSU?

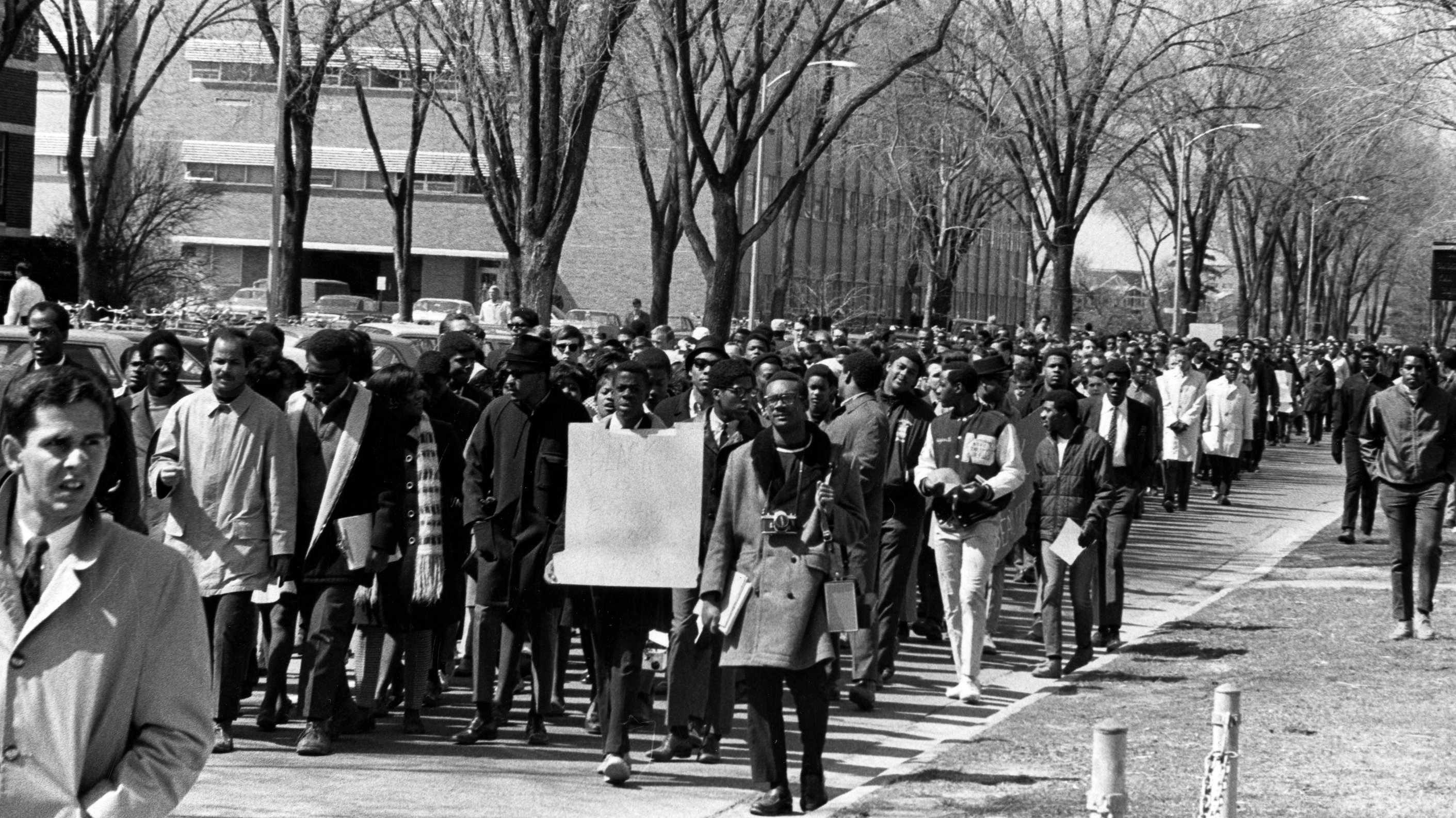

Black students began demanding equitable treatment before the modern Civil Rights Movement. In 1940, for example, incoming student Franklyn V. Duffy refused to allow college administrators to relegate him to the dorm rooms specifically designated for Black students. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the campus NAACP became the most active Black social justice organization. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were numerous Black activist organizations, among the most active being the Black Students’ Alliance, the Black Liberation Front, International, the Black United Front, the Project Grapevine, and the Pan-African Students Organization in the Americas. During the late 1960s, a large portion of MSU’s Black student population came from Detroit, just 90 miles east of campus. Many of these students brought with them a culture of racial solidarity, activism and resistance.

There were two major events in the late 1960s that sparked Black activism on MSU’s campus, leading to significant campus reform. The first was the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, after which Black students mobilized and created a list of demands for President Hannah and the university administration. The other was a sit-in at the Wilson Hall cafeteria in 1969. Over 100 Black student activists — including the Black Students’ Alliance — held a peaceful protest in response to the alleged mistreatment of three full-time Black cafeteria employees. As a result, university administrators engaged in serious discussions with the students and agreed to implement necessary changes.

What role did athletics play in integration at MSU?

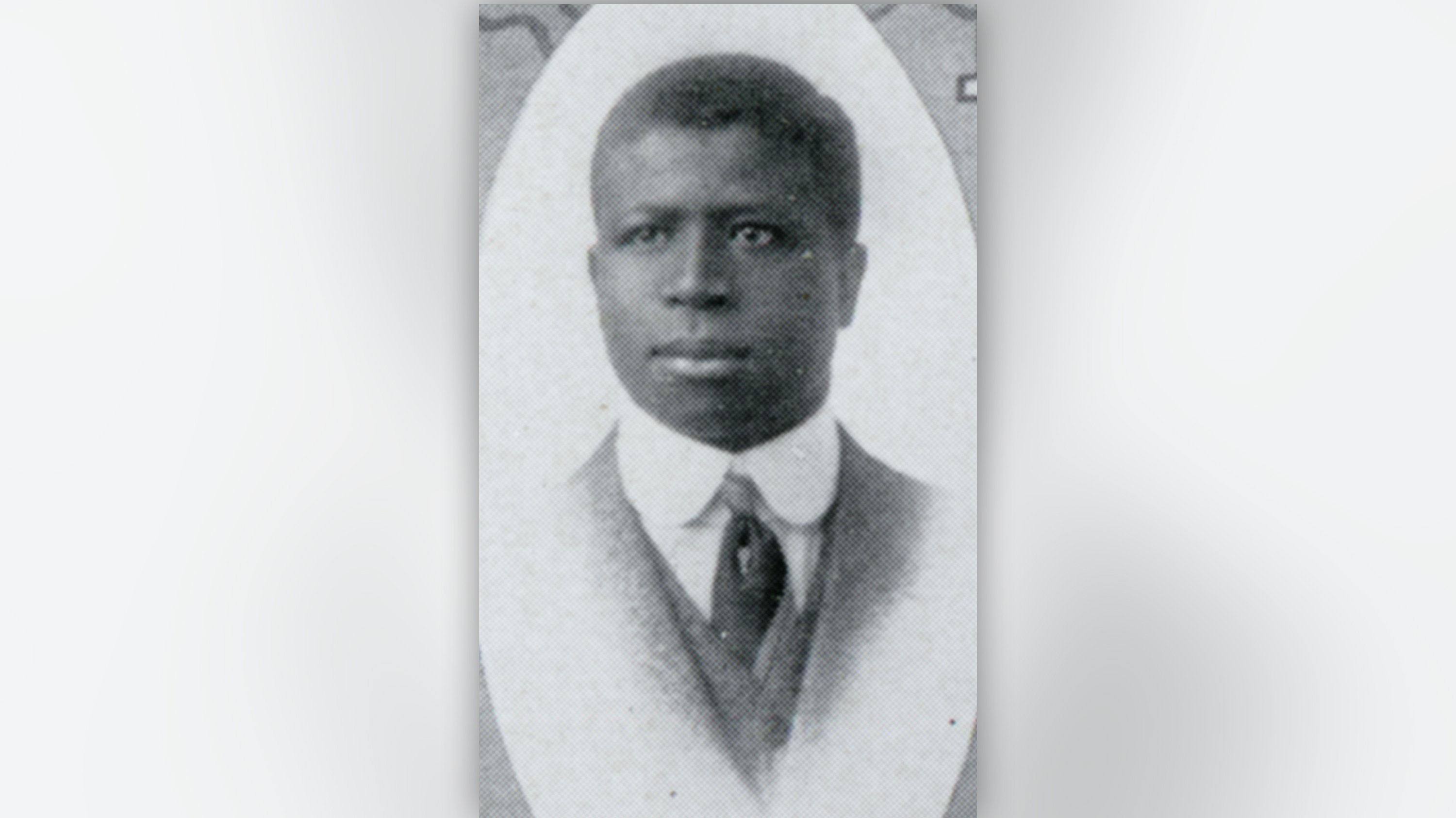

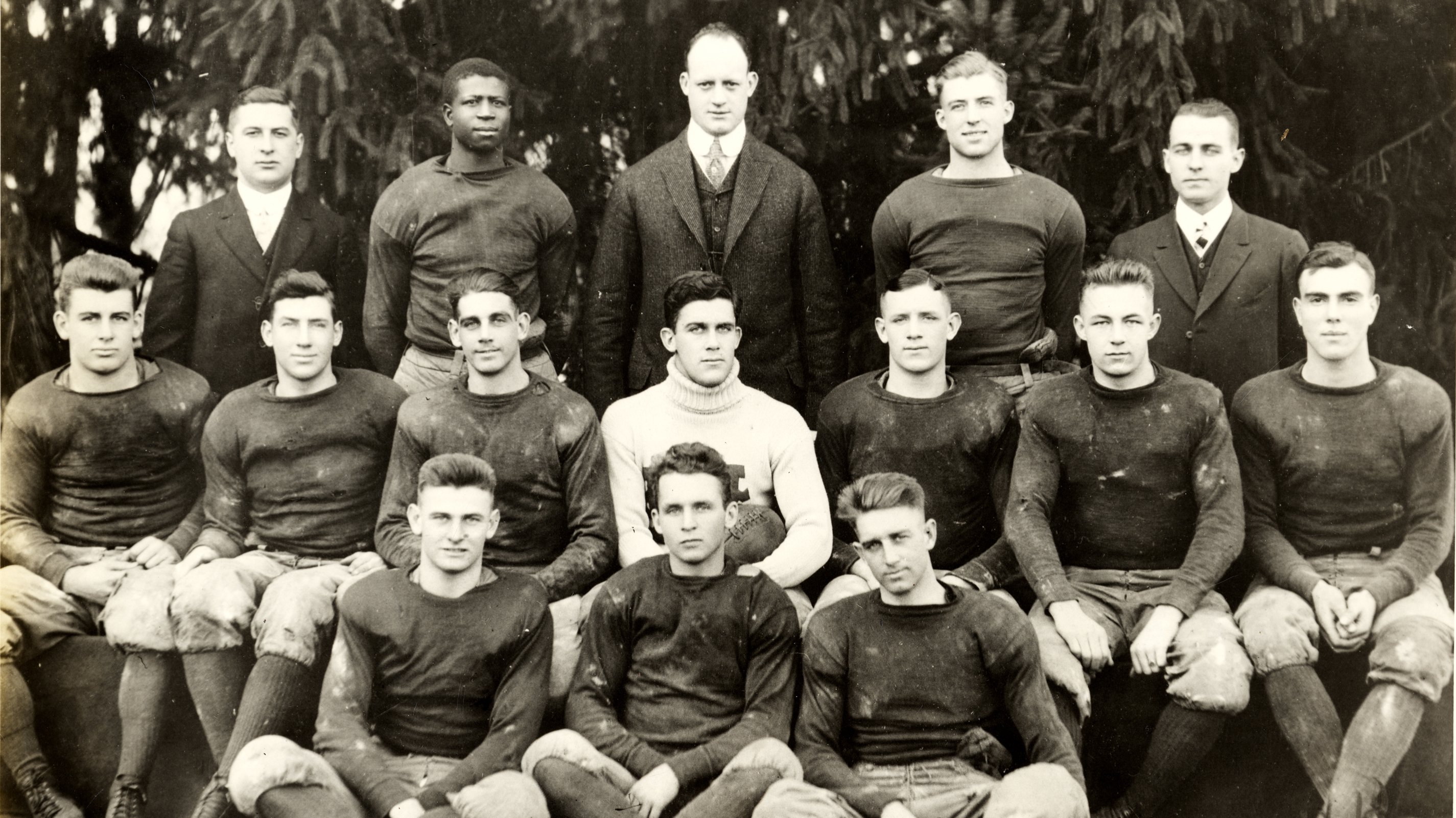

When exploring racial integration at MSU in the area of sports, football serves as a perfect case study. The first Black varsity football player at MSU was Gideon Smith, who joined the varsity team in 1913. He played varsity football during the 1913, 1914 and 1915 seasons under coach John Macklin and was inducted into MSU’s Athletics Hall of Fame in 1992.

Macklin was progressive in terms of race when compared to many of his contemporaries. Following Smith’s time at MSU through the era of World War II, there was just a small number of Black players who made it onto the gridiron.

It wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that we witnessed a much higher level of integration with MSU football. The 1966 team had many Black players, including starting quarterback Jimmy Raye and co-captains George Webster and Clinton Jones.

Under the leadership of President Hannah and coach Duffy Daugherty, this level of integration earned MSU national recognition. During the late 1950s and 1960s, several members of the Black press, for example, even noted that the Spartans looked like a team from a historically black college or university.

Besides athletics, what are some other units on campus that opened opportunities for Black students during the Civil Rights Movement?

During the long Civil Rights Movement, Black students found opportunities to be active in various spaces. During the 1920s and 1930s, a few Black students joined predominantly white social organizations. In the 1940s, students like Gladnil Williams and Julia Cloteele Rosemond spoke out for Black civil rights as members of the Michigan State Student Speakers Bureau. Black men and women also created their own social and self-help organizations in the late 1940s and mid-1950s. A chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Incorporated was charted on MSU’s campus in 1948 and a chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated was charted in 1954. During the late 1950s and 1960s, more than a few Black students found vital opportunities for activism and professional development in the campus NAACP. By the early 1970s, there were more than fifty Black student organizations that offered Black students a range of opportunities. As more Black students attended MSU in the late 1960s and 1970s, moreover, more began to integrate traditionally white units and organizations.

How can people learn more about your book and research?

I will be discussing the book at a public event on Saturday, March 22 at 4 p.m. at Hooked, located at 3142 E. Michigan Ave. in Lansing. I am also the featured speaker at MSU’s Institutional Diversity and Inclusion Speaker Series on April 23.