For decades — and at institutions throughout North America, not just at Michigan State University — the curriculum for the study of music theory at the collegiate level was deep but narrow, entirely focused on Western European classical music and providing little or no choice to students. That is starting to change nationwide, and with the implementation of a new curriculum this year, Music Theory faculty at the College of Music are on the leading edge.

With goals to make sure the curriculum teaches more music by more people in more ways, faculty also set out to ensure students would have a level of choice in their focus.

“The old curriculum was a tradition across multiple institutions,” explained Cara Stroud, associate professor of music theory. “There was a way that you teach music theory, and we were doing that really well.”

Stroud described an inflection point when cultural changes within music theory coincided with external forces, partially spurred by a keynote address at the 2019 Society for Music Theory conference.

“It was thought-provoking for many people, and it was part of this broader moment of cultural change that accelerated in 2020 with the focus brought to violence against Black people. At that time, several MSU College of Music students in the Color Me Music student group brought lists of items that they felt would help them to feel more included in our college. It meant a lot to them to feel like their way of looking at music and the music that was important to them was represented in the theory classroom,” Stroud said.

Professor of Music Theory and Chair of the Music Theory Area Gordon Sly explained that a lot of theorists wanted to broaden the curriculum, but there was a time when the academy of music theory academics held a very strict interpretation of the correct way to teach music theory.

“There was a lot of energy bottled up for decades,” Sly said. “I had fellow students both in musicology and theory when I was a PhD student in the late 1980s who were interested in pursuing research that departed from established norms either of subject or treatment.”

Sly recalled a colleague who was interested in studying the conjecture that Schubert was gay and how that might manifest in his music, and he was told that “professionally, it’s not a good idea.” Such situations reflected the strong sense at the time not only that European-style concert music was the only legitimate subject for serious study, but that there were clearly defined, and sanctioned, scholarly approaches to that music.

As Sly explained, there has “always been a certain energy pushing at those guardrails. Now, we’re in a different place in society, and this idea of ‘this is legitimate, and this is not’ has completely been disassembled. It is curiosity that is driving things rather than permission systems, reflecting more the interests and the breadth of lived experience of our students. It has had an explosive effect on curricula, in more than our discipline.”

Music Theory faculty at MSU reflected on the messages they were sending to students by the music they spent time on in class. Associate Professor of Music Theory Michael Callahan explained that, while there were a few schools that courageously expanded music theory curriculum before the discipline as a whole was ready to accept the change, he takes pride that he and his colleagues at MSU decided to be part of the leading edge by implementing change that was fundamental rather than just incremental.

“I would group change-making institutions into basically two mindsets for approaching revisions to their undergraduate theory curricula. There are ones that have added a few side dishes while preserving the main course, and there are ones that have dumped the plate altogether and sought to create a more balanced meal. My colleagues and I decided at the very beginning to be the latter. We weren’t interested in adding a little bit of diversity to a structure that still would prioritize white, European classical music. We were interested in interrogating and dismantling the existing curriculum in order to achieve something that’s fundamentally different—something bolder that centers and values important musics, musicians, and ways of making music that had been marginalized for too long. Curricular reform is never done, but I’m proud that we’ve taken the harder, braver, more impactful of these two paths,” Callahan said.

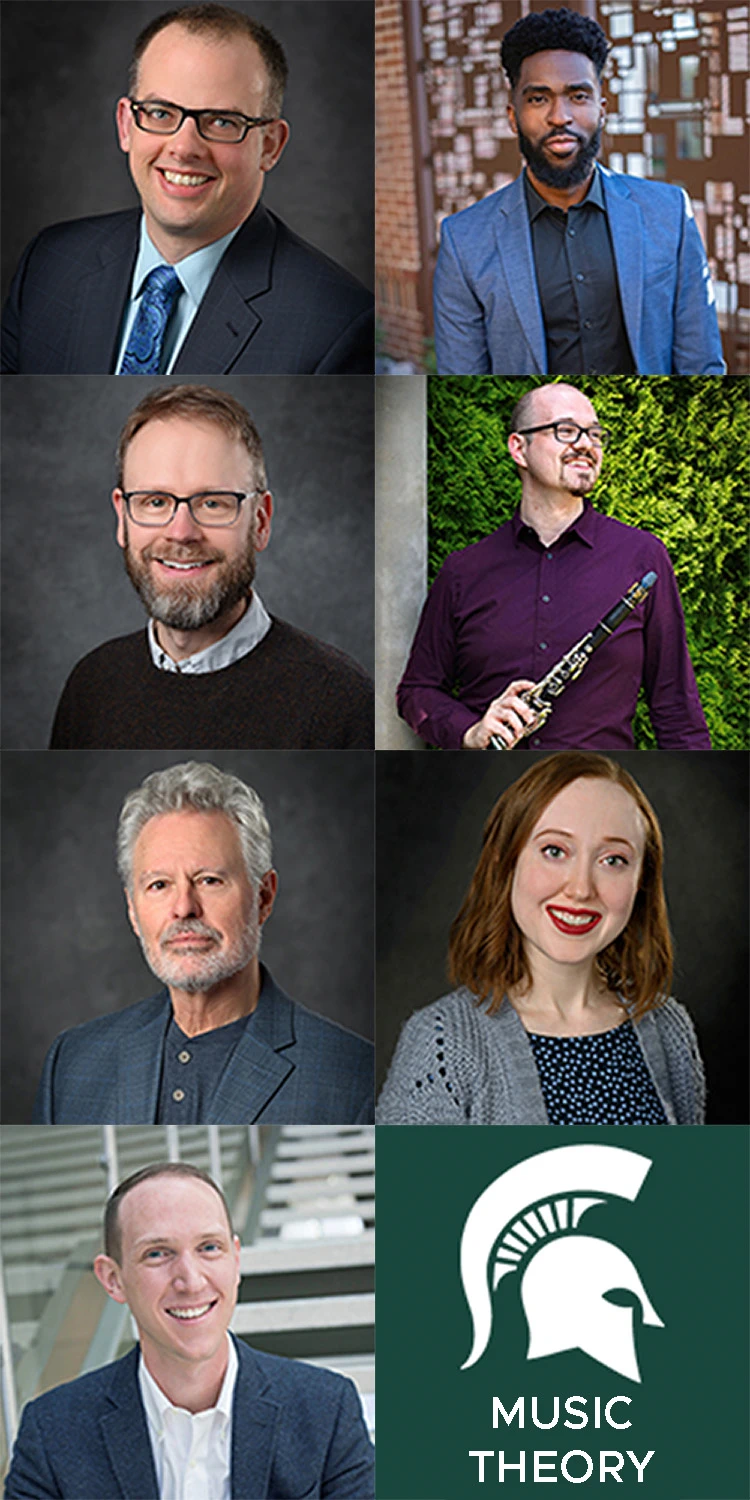

He explained that the ability of the seven MSU Music Theory faculty members to get along, share disagreements, and reach a consensus is a primary reason a transformation has become reality. Between Callahan, Sly, and Stroud, as well as music theory assistant professors Richard Desinord, Patrick Johnson, Nick Schumacher, and James Sullivan, there are a variety of research interests, but what faculty research is not always what they teach.

“We all believe in and are willing to redesign classes and undergo the vulnerable experience of teaching something we’ve never taught before, that we never even had the opportunity to study — something that’s outside what we would draw as our range of expertise, which, for some of us, is going to be entire courses,” Callahan explained. “Some of the reasons that can derail change like this, that I know have happened at other institutions, have not happened here, and I don’t take that for granted.”

Zachary Lookenbill earned his Master of Music degree in music theory from MSU in 2021 and went on to Ohio State for his PhD. He is now an assistant professor of music theory at the University of Arkansas. His early career success, participation in MSU theory curriculum discussions, and the changes that followed with the intention of further engaging students, point to the alignment of the new theory curriculum with MSU and College of Music student success initiatives.

“The music theory faculty at MSU were committed to engaging in conversations with music theory graduate students and teaching assistants,” Lookenbill said. “I began to understand during my time at MSU that change in the music theory classroom did not only apply to the demographics of composers, but also a wide range of musical styles, musical elements, and classroom activities that might make learning music theory more engaging.”

Those discussions, Sly explained, resulted in moving away from a curriculum that led students through a list of required courses with little variation from the list. Today, that foundational knowledge is still part of the curriculum, but students can assemble a package of courses that aligns with professional interest and curiosity.

“We are now able talk with students about designing a set of electives that will fulfill their requirement but also benefit the student in targeted ways,” Sly said. “The curriculum is so much more nimble and able to be meaningful to many more students on a much more intimate and nuanced level. That’s one of the main strengths.”

Sly and the entire Music Theory faculty at MSU are excited to see the outcomes of the new curriculum over time, and their focus on evolving and learning what is best for students remains strong.

“I really love being a part of the Music Theory Area at Michigan State because we continually look at things that could be better,” Stroud said. “That growth mindset is so positive for our students and for us as colleagues.”

This story was originally featured on the College of Music website.