Big data that flow through a computer are a hot research commodity. But the mothership of big data is analog -- local, accessible, as well as dried, pressed, stuffed, bottled, pinned. And indispensable.

Michigan State University’s vast collections of preserved mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, fishes, fossils, insects, and living and preserved plants are essential components of world-class scientific exploration and education.

The collections face crucial reckonings driven both by significant retirements and by swelling stresses on the systems that support them. And it’s not just at MSU. Duke University announced in February it is closing its renowned herbarium, a move deemed “a tragic mistake” by scientists quoted in Science Magazine.

The MSU Museum is home to more than 117,000 vertebrate specimens. The Albert J. Cook Arthropod Research Collection has 1.5 million insect specimens stored in the Natural Science Building. The MSU Herbarium has 520,000 specimens in over 3,000 square feet of space and a conservatory spans two greenhouses.

“The guts of the museum are the collections, that’s what makes us a museum,” said Devon Akmon, director of the MSU Museum. “We see ourselves as critical infrastructure to support academic missions, but we’re hitting the ceiling for space, and we are at the crux of radical transformation.”

Collections are crucial to addressing some of the world’s most pressing challenges such as climate change, dwindling biodiversity, and habitat loss and conservation. Old specimens are valuable precisely because they preserve and verify the past, and that lineage is added to regularly. Entomology students routinely contribute specimens of their research subjects. Mammal curators rush to gather, say, a porcupine carcass because it can be a tangible data point that could clarify habitat range change.

Collections are a treasure trove as new technologies emerge. An ancient bug, bird or plant can deliver new answers to questions and tests not even imagined today, just as today’s genetic testing unlocked information unimaginable in the 1800s. That value only exists if the specimen is maintained.

Barbara Lundrigan, an Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior (EEB) core faculty member, recently retired as curator of mammalogy and ornithology at the MSU Museum. She noted that MSU’s vertebrate collections, which include specimens dating back to 1844, are crucial to addressing modern questions. They’re the standard by which previous findings are validated – and a foundation for new discoveries.

She was involved a decade ago in a study showing that some Michigan mammal species have expanded their geographic ranges northward, often displacing northern relatives, apparently in response to climate change.

When it came to the northward expansion of the white-footed mouse (an important vector for Lyme disease), museum collections served a vital role - providing both historical range data and specimens whose identification could be directly verified.

“If you can’t access the animal, you can’t verify that the species name recorded years ago could indeed be wrong, Lundrigan said. “You have to have that original; I can’t imagine how you could ever replace the real thing.”

Having the opportunity to lay eyes, and sometimes hands, on the specimens makes the science stronger. Hannah Burrack, chair of MSU’s entomology department and EEB member, said the collections are a needed check for human fallibility. Consider that there are 3,500 different kinds of cockroaches.

“While there are many experts, there aren’t enough to be expert on every species of insects,” she said. “Keeping specimens preserved and allowing people to have access to them is very critical.”

The examples are abundant – Lundrigan said that according to Google Scholar, worldwide every 2.4 days a new paper comes out that cites the vertebrate collections.“Michigan State’s legacy as a leader in critical research across the natural world has strong roots in our vast collections. We are committed to not just maintaining and growing these important resources, but also continue to support the collections with wise, science-based governance.”

When Michigan scientists were scrambling to identify the mystery beetle that was decimating its ash trees, they came to the entomology collection to determine that it was not one of the thousands in the collection, and ultimately learned it was the emerald ash borer.

“That borer destroyed millions of ash trees and altered the ecology of Michigan forests,” said Anthony Cognato, collections director. “This rapid identification allowed foresters to take quick action to combat this invasive forest pest. Insect collections are treasure troves of biological data including new species just waiting to be discovered.”

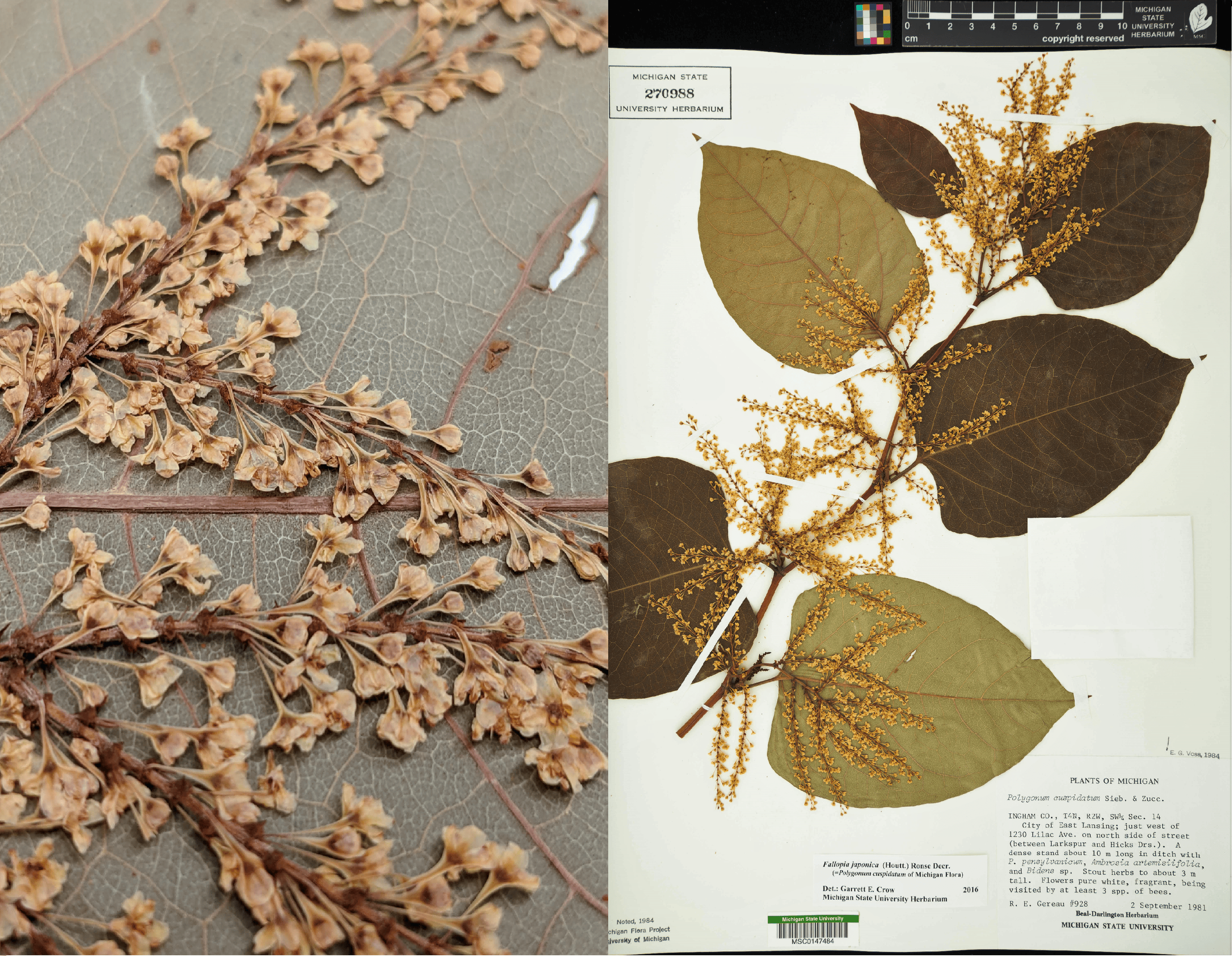

Like all the MSU natural science collections, the vast plant collections are used by scientists worldwide as well as in undergraduate and graduate teaching and by the public, with almost 300 articles published worldwide in the last three years citing the MSU Herbarium collections. Plant biology chairperson and EEB faculty member Andrea Case noted that 4,000 people a year visit the plant collections and conservatories alone, including visual artists seeking subjects. The conservatories are a refuge for valuable plants recovered by officials from poachers, notably many of the orchids in the collection.

“What we have,” Case said, “is representation across the tree of life. The conservatory gives the MSU community access to some of the most exotic and unusual plants from across the globe—it’s the equivalent of a plant zoo. It supports our research and teaching missions and fosters a fascination of plants in visitors of all ages.”

As ways of scanning, digitizing, and sharing in increasingly sophisticated databases advance, plant collections are a widely used research resource, especially during the pandemic when travel was restricted.

In the journal BioScience, Alan Prather, herbarium director, interim director of the W.J. Beal Botanical Garden, and an EEB core faculty member, co-authored an article tracking the evolution of plant collections, in which it was noted, “Specimens are increasingly used in ways that influence our ability to steward future biodiversity. As we enter the Anthropocene, herbaria have likewise entered a new era with enhanced scientific, educational, and societal relevance.”

To Akmon, harnessing technologies’ potential presents enormous opportunities for collections – and museums. A $2 million NSF grant is pending for MSU to transform more specimens into digital format.

The list of needs to take collections into the future is long. Training will be needed to use new technology. He said it is time to evaluate the feasibility of bringing collections under one search umbrella to better enable the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of research.

And collections invariably fall under the bigger tent of information, as science communication sprawls far beyond the walls, or even the provenance, of museums and libraries.

“We are now at a crossroads,” Akmon said. “There are so many places you can go now for immersive environments. How do we think more boldly? How do we build on the success of our faculty curators?”

As retirements in that field mount, Akmon said support for continuing that model is strong, and discussions with the colleges and departments center on recruiting the next generation of faculty curators who understand the value of biological collections and their critical role in supporting a future of stewardship and discovery.

“Faculty curators are essential to what we do,” he said. “The magic and power of the science collections would not be it without them. Wouldn’t be integrated in teaching and learning without their backgrounds.”