For the third year in a row, researchers from Michigan State University’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources partnered to place unique identification bands on peregrine falcon chicks to monitor their movements and to help the species recover.

While some might be saddened to learn that this year’s banding ceremony is likely the final one between MSU and the DNR, it’s for a good reason — the project has been a success, and the species status has been reduced from a state endangered species to a state threatened species.

The story of the MSU peregrine falcons

The MSU Fisheries and Wildlife Club helped secure a nestbox on top of Spartan Stadium in 2022 to encourage reproduction, when the banding first began. Three falcon chicks were banded this year, Reggie, Acorn and Franklin, marking a total of 10 chicks in the three years. Spartan Stadium has served as one of 30 nesting locations across the state, providing falcons a space to adapt to human environments and thrive.

Jim Schneider is a senior specialist and undergraduate program coordinator in MSU’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources who has been involved with the banding project.

Since the early 2000s, peregrine falcons have been sighted around campus. Nest boxes were previously set up at the old campus power plant and Hubbard Hall but, unfortunately, the peregrines never used the boxes in either location, according to Schneider.

“Eventually we just started listening to the birds. They’d been frequenting the south end of Spartan Stadium for several years. We finally just said, 'if that’s where they prefer, let’s try and make it happen,'” Schneider said. “The MSU Fisheries and Wildlife Club approached the Spartan Stadium facilities staff with their idea, which they enthusiastically supported, and the rest is history, ten peregrine chicks later.”

How the banding process works

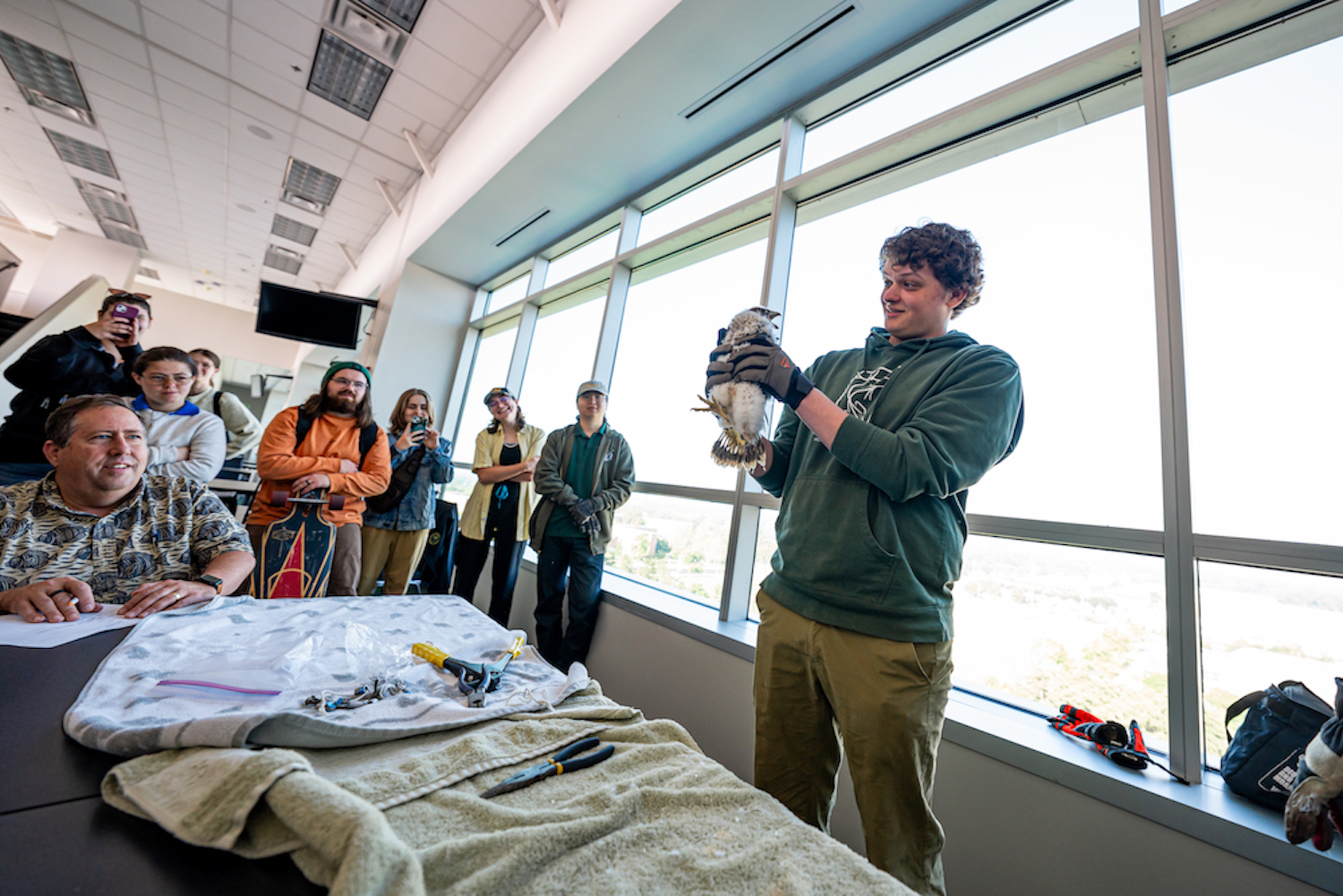

At MSU, the banding took place on June 3 inside Spartan Stadium, led by MSU and DNR staff, with MSU students from the Fisheries and Wildlife Club also in attendance.

The process involved researchers, wearing hard hats and holding umbrellas for protection, first carefully removing the falcon chicks from their nest on the top of the stadium. Because falcons will defend against anyone who invades their nest, it is paramount the team work swiftly and safely. Then, when the chicks were settled inside, the team was able to attach the bands quickly, with some squirming from the chicks. They were then returned to their nest.

Since the banding started in 2022, it has become "not just about the falcons, but the East Lansing community, engaging local schools and residents alike," according to Will Herbert, vice president of the MSU Fisheries and Wildlife Club.

“Peregrine falcons are an endangered species in Michigan, so it's an intimate opportunity to see the falcon at its most vulnerable stage of its life,” Herbert said. “The banding is a sort of sending away party for the falcons before they are developed enough to leave the nest, and it is a good representation of some professional work in the field of Natural Resources and Conservation.”

For those who have followed the falcon chicks from past years, they are doing well. 2023’s Swooper had to be relocated, as the young falcon was living near the Willow Run Airport, and Pickles, who was injured by a car, resides at the Howell Nature Center. Learn more about the past three clutches with the MSU Fisheries and Wildlife Club’s falcon box timelines.

The history of falcon banding

Banding, which allows researchers to track migration patterns and the dispersal of the species, first started when peregrines were reintroduced in Michigan from 1986 through 1992. Since then, every falcon chick has been a wild produced bird. More information about falcon migration and tracking is available from MSU Extension.

Falcon banding has been occurring for several decades, according to Chad Fedewa, wildlife biologist with the DNR, who has worked with MSU on the banding.

“Since the 1970s, reintroduction efforts over the ensuing decades allowed for the peregrines to reach a point where they were no longer classified as federally endangered nor threatened in 1999; however, recovery efforts continued in Michigan where they were still listed as a state endangered species,” Fedewa said. “The goal for the Michigan DNR was to have 10 nesting pairs and, by 2006, there were 13 pairs nesting with 10 successfully producing young that year.”

The falcon population had struggled from the 1940s through the 1970s due to the widespread use of pesticides, specifically DDT. The chemical was discovered to be in prey species that peregrines fed on, resulting in their eggs thinning and a decline in reproductive success, Fedewa explained.

So, in the 1970s, DDT was banned and laws like the Endangered Species Act and Migratory Bird Treaty Act were passed, promoting population recovery.

The possibility of continued banding

As the falcons are now less threatened, this banding is the last one planned at Spartan Stadium in partnership with the DNR. However, the Fisheries and Wildlife Club is working with Jennifer Owen, associate professor in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, to continue banding in the future with permits pending.

“Part of the recovery effort was introducing peregrines to urban areas and installing artificial nesting boxes. While peregrines have returned to more natural nesting areas such as cliff tops in the Upper Peninsula and some islands of the Great Lakes, they have adapted well to urban environments and have been very successful nesting on large buildings, bridges and other manmade structures,” Fedewa said.

To stay updated the MSU falcon chicks, information will be posted here and consider supporting the MSU Fisheries and Wildlife Club.

Peregrine banding has been a great conservation success story, and locations like Spartan Stadium are just one of those places helping in the effort.

So, if you make it to a football game this fall, do not forget to wave to the falcons, or check in on them any time via the Spartan Stadium Falcon Cam and from this view.