The first time Jack Schulte touched a research telescope was at the Michigan State University Observatory.

The astrophysics Ph.D. student spent his undergraduate years at Arizona State University studying theoretical research. His work was based on data and scientific papers, not on observing the stars for himself.

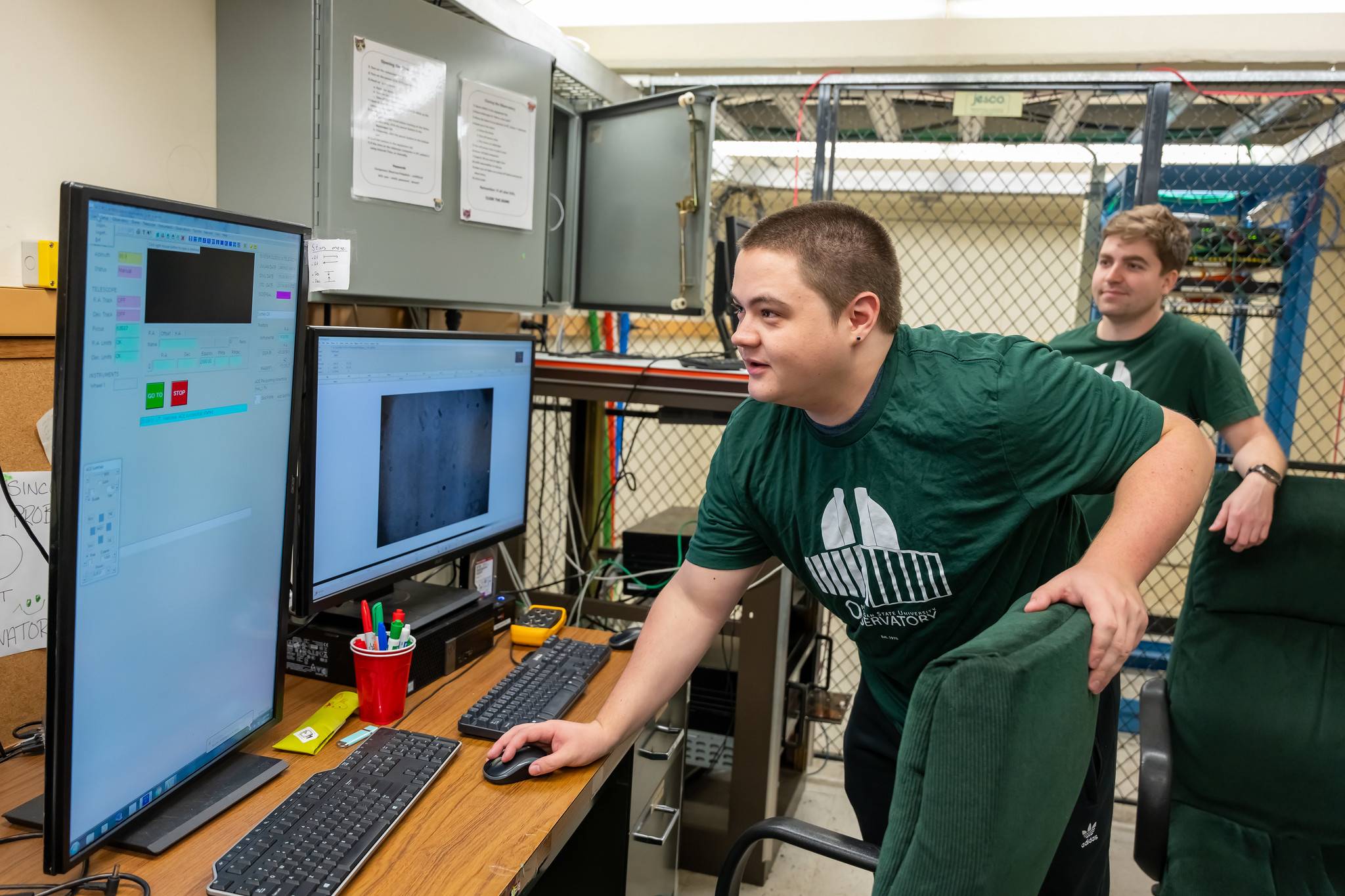

All that changed when the MSU Observatory Research Program, or MORP, immediately put him to work. Every clear night, Schulte and other MSU astrophysics students open the Observatory roof and point the telescope at the stars. From sunset to sunrise, they track planets, stars and changes in light that could signal significant details about the universe.

“Here, you actually see the things that become data and scientific papers,” Schulte said. “You learn to take the data yourself. It’s an opportunity you don’t often get. And many institutions don’t have something like this.”

For the last decade, MORP has provided undergraduate and graduate students alike with real-world research experience and helped them to decide if astrophysics is the right career path. Anyone who’s passed Astronomy 208 is welcome. Other than a hiatus during the global COVID-19 pandemic, MORP has held strong in training up a generation of future astrophysicists.

Physics and Astronomy Professor Laura Chomiuk started MORP as a way for students to get involved in research early in their educational careers. Not only does the work provide them with extra cash, but it’s also resulted in academic papers and even important NASA discoveries.

“Every student who enters Michigan State should have the opportunity to have an experiential learning opportunity within their major,” Chomiuk said. “MORP was designed to help us meet that goal.”

MORP is based on an organization Chomiuk joined as an undergraduate student at Wesleyan University. Instead of getting a job in food service or in retail, she was paid to observe the sky from a telescope one night a week.

The Observatory, located on Forest Road, was built in 1970 to be used for research. Later, Professor Emeritus Horace Smith kept the facility active and began using it for student projects. Chomiuk took over the MSU Observatory when Smith retired.

Her goal in starting MORP was to engage a large number of students in authentic research experience. That’s especially valuable as the number of astrophysics majors at MSU has exploded, said Joey Rodriguez, assistant professor of physics and astronomy who leads MORP with Chomiuk. A few years ago, the department only had 10 to 20 astrophysics majors. Today, that number has exploded to more than 40 a year.

Chomiuk and Rodriguez want those students to have a chance to do research, regardless of their backgrounds or the opportunities they had before coming to MSU. That’s why the only requirement is Astronomy 208, a class that teaches students how to observe the sky, how to do data reduction and other tasks they’d use in the Observatory.

Students in MORP develop a sense of community and belonging, Chomiuk said. They gain a sense of ownership over their discipline that she says helps keep them in their classes and leads to more retention in the astrophysics major.

“I really believe in this synergy between research experience and academic success,” Chomiuk said. “That’s my biggest goal.”

Under the dome

The way MORP works is three students are assigned to work the Observatory every night, depending on clear weather. They’re tasked with observing different phenomena, whether that’s an ongoing MSU research project, a national effort or a NASA mission. No matter the night, there’s always something to see, Rodriguez said.

While Chomiuk, Rodriguez and other faculty sometimes come to observing nights, the program is almost entirely student-run. The students observe phenomena all night, extracting the data through the processes they learned in Astronomy 208. For example, they could help confirm the existence of an exoplanet by tracking when the light from a star is blocked by the planet passing in front of it.

The students’ shift begins at sunset and lasts until sunrise. Every 15 minutes to half an hour, they move the telescope a tiny bit and take images using a camera attached to the telescope. In between, they’ll do data reductions or finish homework. They keep a case of Red Bull handy to help them stay awake into the early morning hours.

Cameron See, a fifth-year astrophysics major, said the images themselves are a little lackluster. To the untrained eye, they look like white dots on a black screen. The real excitement is in what those dots represent.

“It’s cool when you reduce the data and you see the actual transit,” See said. “When you see the light curve, you know that that’s actually a planet in some distant solar system.”

Working in the observatory is perfect for students who don’t thrive in the classroom setting. Rodriguez remembers what that was like. As an undergrad, he never cared for studying or sitting through lectures. But in a lab, he was in his element.

Students in MORP get to see data for themselves, not just read about it in a book.

“MORP lets us teach them in a way that allows them to work hands-on the way they would in the field,” Rodriguez said.

Nights under the stars

When Chomiuk came to MSU, she saw the observatory as an opportunity to engage the public and teach them about astronomy. She built on Horace Smith’s past efforts to sustain and strengthen a public outreach program. From April to October, the doors are opened two nights a month to anyone who wants a chance to look through the Observatory’s 24-inch telescope. Smaller telescopes are also set up on the lawn.

While people wait for their turn with the telescope, MORP students run educational programming to teach people about what they’re seeing in the night sky. On warm nights, hundreds of people show up.

Schulte said the crowd ranges from people who’ve never stepped foot in the Observatory to passionate regulars. He’s seen 10-year-old children talk about calculus and ask questions about Galilean moons. And he’s seen people cry as they look through the telescope and see Saturn for the first time.

“You see the avid learners, and then the casual people who come to be wowed,” Schulte said. “Lots of people come back, which is a good sign.”

An eye on the future

Chomiuk’s hope is that MORP helps astrophysics students explore careers, determine if they want to pursue graduate school and prepare to apply for programs.

Cameron has enjoyed his experience with the Observatory so much that he doesn’t want it to end. After graduation, he hopes to go on to work in another observatory. He’s applying for several positions, including the IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica.

At MSU, Rodriguez and Chomiuk want to find ways to include more students to accommodate the growing number of astrophysics majors. They also hope to upgrade equipment and make renovations such as improving accessibility. The Observatory has served students and the community for more than 50 years. Chomiuk and Rodriguez hope to preserve and improve the iconic facility to serve future generations.

This story originally appeared on the College of Natural Science website.