Science, too, has a sniff test. It’s known as chemotaxis.

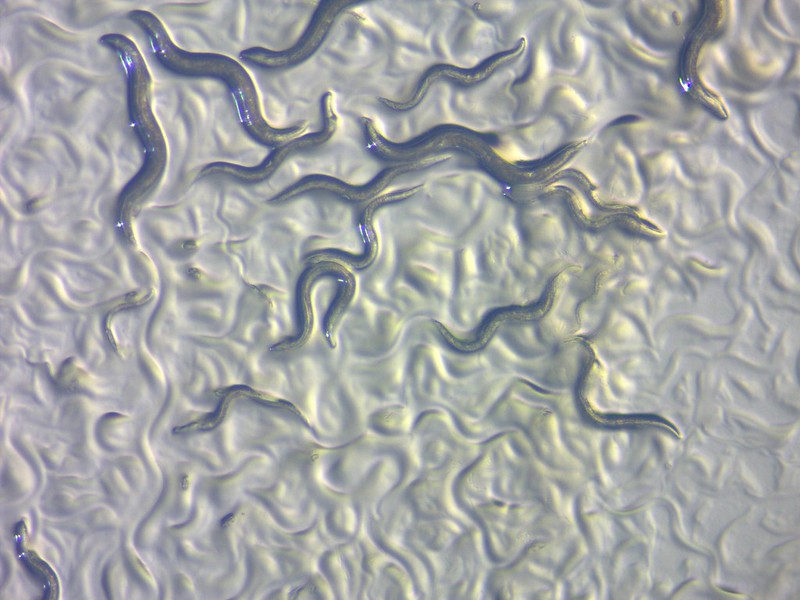

Plants have evolved to produce a remarkable array of small molecules. Sometimes, those molecules can be beneficial and valuable. Other times they can be benign, or even deadly. For ages, the surest way to distinguish one from the other has been to dab a bit of the molecule at one end of a petri dish and drop tiny nematode worms — C. elegans — at the other, then wait to see if the worms move toward or away from the compound in questions.

This so-called “artisanal” method, however, is achingly slow.

Now, in a collaborative paper appearing in PloS Biology, researchers from Michigan State University and Stanford report a breakthrough that greatly speeds up this process. The paper reports the development of software that turns an off-the-shelf flatbed scanner into a lab tool that can evaluate dozens of chemotaxis samples in minutes.

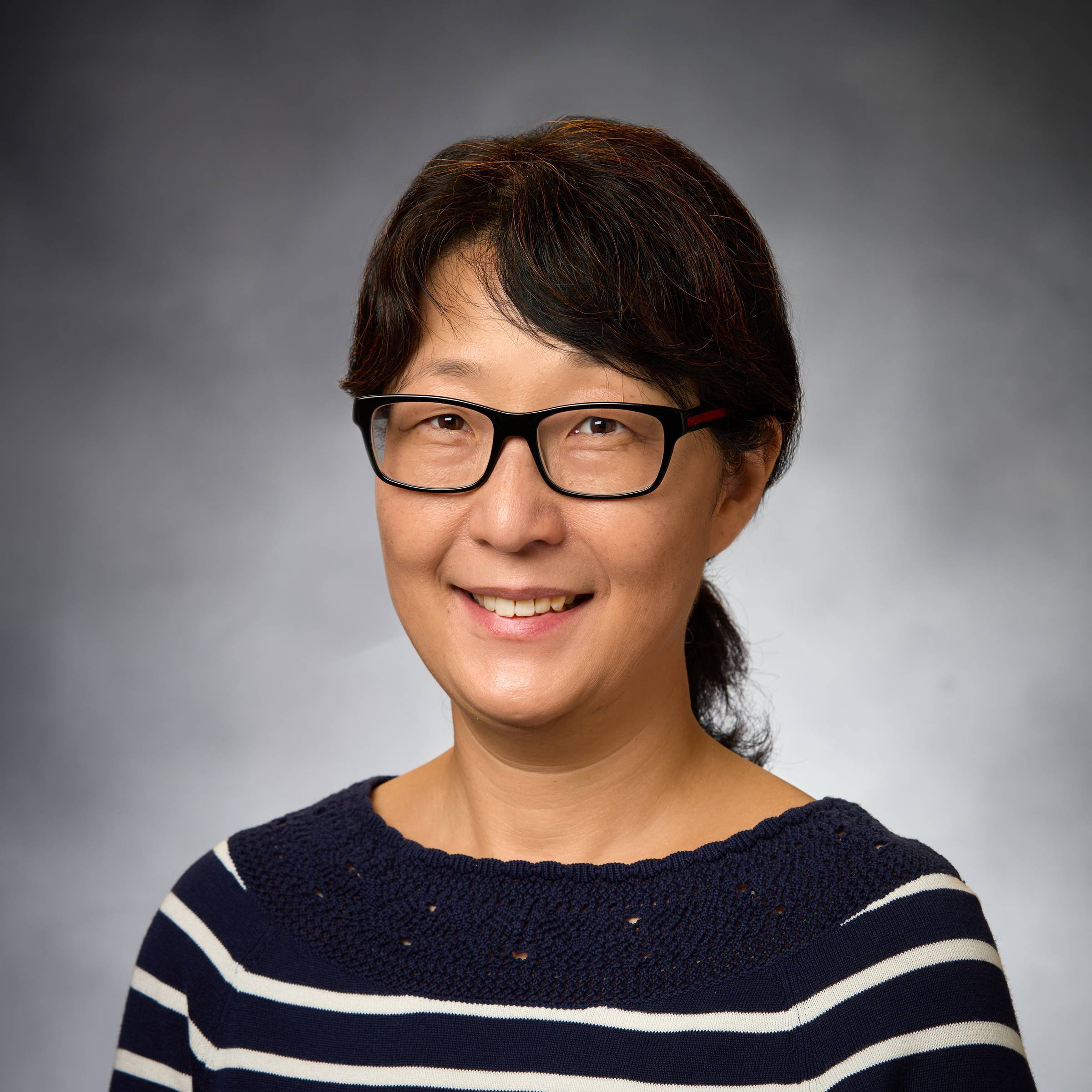

Seung Yon "Sue" Rhee, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology in MSU’s College of Natural Science and director of the Plant Resilience Institute, leant her world-renowned expertise in plant biology to the project.

"Most of the hundreds of thousands of compounds that plants produce, we know very little about how they are used in nature. A long-standing dogma is that they are used to defend against pests or attract pollinators, but only a tiny number of these compounds have known roles,” Rhee said, who also holds appointments in MSU’s Department of Plant Biology and Molecular Plant Sciences Program.

“Through this ingenious high-throughput chemotaxis assay, I hope that we can start to unravel these chemical mysteries at scale."

The project was led by a team at the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford University and Miriam Goodman, a professor of molecular and cell biology.

Where once it might’ve taken researchers two hours to assay a single new molecule, the new system can perform 80 chemical assays in just three minutes.

“In the artisanal days, if someone were really skilled and had done all the prep work and had all the materials, it might take two weeks to do that many assays,” Goodman says.

As well as identifying the components of their DIY tool in the latest paper, the team also provides their code for free.

It sounds simple, but developing the tool has been anything but for the team. It took more than five years to design, create and test the tool from inception to publication.

The project was seeded by the “Big Ideas in Neurosciences” initiative at the Wu Tsai Institute. These flagship research projects include five-year grants and charged specifically with bringing together teams of diverse researchers to gain deeper understanding of the human brain and behavior in health and disease.

Goodman’s team required experts in neurosciences, animal and plant biology, laboratory sciences, mechanical engineering, and computer science. The team now hopes the tool becomes ubiquitous and leads to rapid discovery of promising new molecules for use in medical, biology, and neurosciences labs currently mired in the artisanal methods.

“With this DIY approach to analyzing plant-made small molecules with unparalleled speed and efficiency, we’re opening the door to exciting discoveries in the realms of plant science and human health,” Rhee said.

“In the nematode research community, there are roughly 1,200 labs across the world,” Goodman notes. The tool could prove useful for discovering other kinds of chemicals or maybe even nematodes that eat bacteria, she says.

“One might use it to find out which bacteria are most attractive to the worms. We're starting to roll up collaborations to look at that,” Goodman adds.

This story originally appeared on the College of Natural Science website.