Since founding the Citing Slavery Project in 2020, Michigan State University Professor Justin Simard and his students in the College of Law, have collected more than 12,000 cases involving enslaved people and more than 40,000 cases in which judges and lawyers have cited these cases as precedent.

When Simard was conducting research for his dissertation, he came across a case predating the Civil War related to slavery that was cited as precedent in 2012. He started looking for other slavery citations from the past 30 years, thinking he’d find one or two, but that wasn’t the case.

“What I thought would be a footnote in my dissertation highlighting the odd decisions of a few judges turned into a broader examination of the legal profession’s treatment of slave cases,” said Simard.

“These have resulted in the persistent legacy of the law of slavery. I want to use this discovery to make the legal profession better.”

He has reason to be hopeful.

“Our work has prompted judges and lawyers to reconsider the way they use citations and reflect on how those citations may have shaped the legal rules in those cases,” Simard said.

Judges from state supreme courts and courts of appeal around the country are asking for training sessions. Law professors are asking for class presentations. High school government teachers want to integrate his work into their classrooms.

Later in July, Simard will address the National Association of Women Judges.

“These judges and lawyers are interested in trying to improve the profession,” Simard said. “They can do that by using our database to find whether the cases they are citing in their opinions or their briefs are based on cases involving an enslaved person.”

And, if so, they have two choices: don’t use that case or acknowledge it with “enslaved party” or “enslaved person” as part of the citation and consider the way slavery may have shaped the opinion.

Citing slavery cases as precedent is wrong for two reasons, Simard said. It causes legal harm as well as harm to dignity.

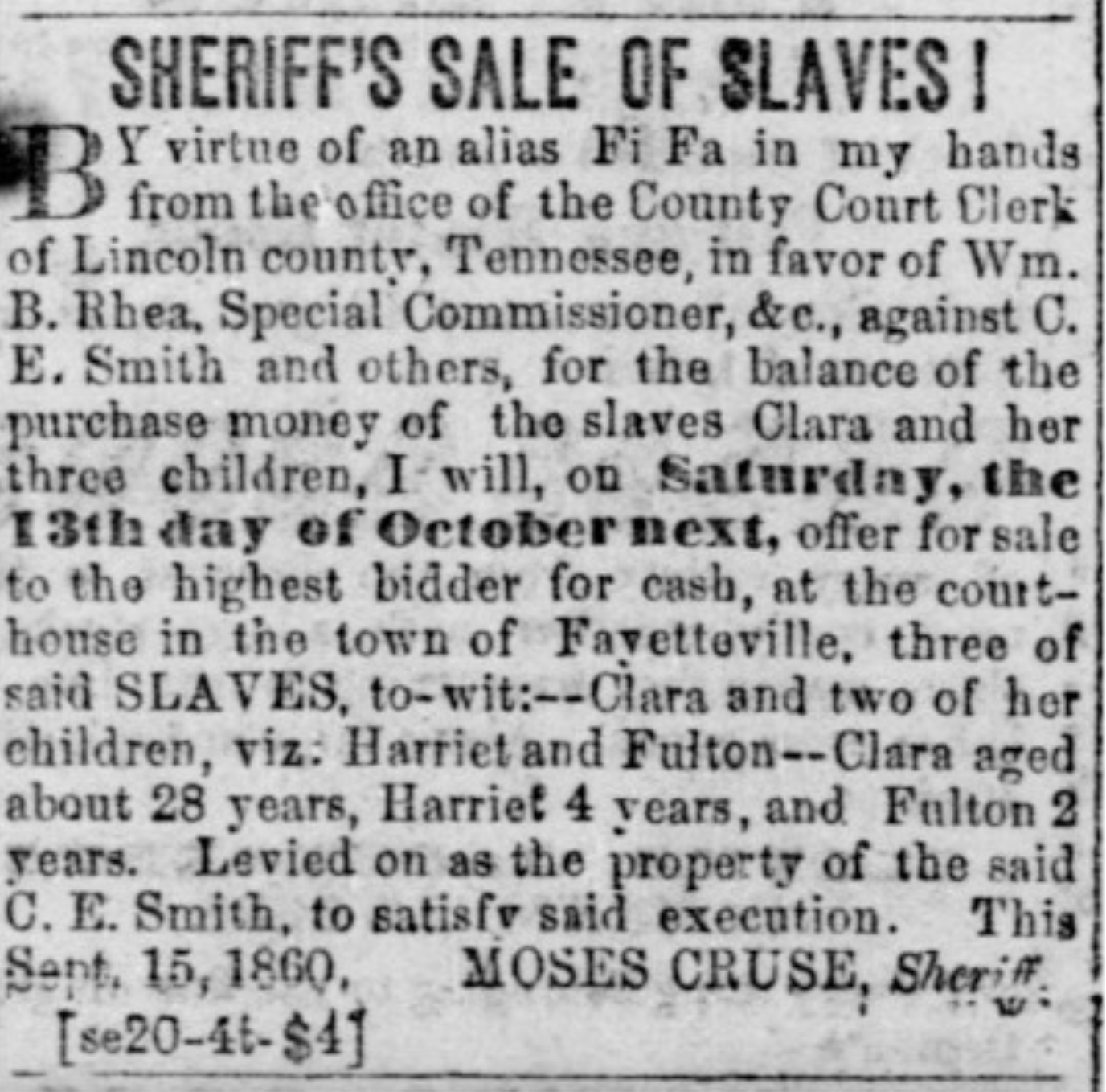

“If a judge relies on a legal rule designed to protect slavery, that’s a legal harm,” he said.“Relying on cases that treated people as property causes dignitary harms by continuing the dehumanization of slavery.This was a tragic era in our country’s history. Judges are in a position to atone for that period by drawing attention to the role courts have played in perpetuating this harm.”

Simard’s research has found slave cases that are not only cited in modern day lawsuits and court decisions but are also studied in law schools without students knowing their origin. He points to a pre-Civil War case uncovered by his research in which the defendant’s name is followed by the words, “a slave.” By the time this case made its way into a current day casebook, the words “a slave” were deleted.

“If the law school casebook had stated the case was about a slave, students would question the outcome,” he said. “Knowing the standards for trial and conviction were different for slaves, students would have a more complex conversation, a bigger conversation."

Simard and his students — who have played an essential role in this project — are taking his research to courts in Oregon, Michigan and California. They have spoken to a law firm in Florida and law school classes in Texas and New York. They’ve also provided continuing legal education classes to lawyers in Ohio, North Carolina, Minnesota, Missouri and Washington.

His students also are working with high school teachers in Detroit and Ferndale, Michigan, to write curriculum for government, social studies and history classes. Ultimately, the curriculum will be available to high school teachers across the country.

Meanwhile, Simard and his students are planning the next phase of the Citing Slavery Project — examining the way slavery cases have influenced the laws around the repossession of property and the way that citation practices have helped obscure slavery’s legacy.

His article “Slavery, Self-Help and Secured Transactions” is scheduled to be published early next year by the California Law Review. In 2023, Simard’s article “The Precedential Weight of Slavery” was published by the New York University Review of Law and Social Change.