This summer’s hazy skies caused by the wildfires in Canada prompted air pollution to rise to the center of attention in Michigan and across the nation. Alerts issued by state and federal agencies warning against prolonged outdoor exposure to the lingering smoke gave way to serious public health concerns.

Jack Harkema, University Distinguished Professor in Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, and the Albert C. and Lois E. Dehn Chair in Veterinary Medicine, has devoted his nearly 30-year career at Michigan State University to understanding the health implications of commonly encountered environmental and occupational air pollutants (like ozone and particulate matter) found in both urban and rural communities.

Prior to joining MSU in 1994, Harkema worked nearly a decade at the Inhalation Toxicology Research Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico (now the Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute) studying respiratory health effects caused by burning fossil fuels.

Over the years, the board-certified pathologist, veterinarian and inhalation toxicologist has examined how inhaled air pollutants, including those from wildfire smoke, can exacerbate and even lead to the onset of chronic medical conditions such as asthma, obstructive pulmonary disease, Type 2 diabetes, as well as cardiovascular, metabolic and autoimmune diseases.

Before the Canadian fires in late June, Harkema secured a new $452,500 grant from the National Institutes of Health to continue research with the University of New Mexico to examine the health effects of metal content and neurotoxicity in wildfire smoke. The researchers applied for funding, in part, because of the wildfires that had previously ravaged the U.S. West Coast. At the time, they had no way of knowing the wildfires in Canada that would eventually cause further alarm close to home.

“I focus on work that is very applied,” said Harkema, director of the Laboratory for Environmental and Toxicologic Pathology at MSU. “Even though we do basic research on laboratory animals (mainly mice) to look at mechanisms of all these pollutants and their potential harm, we’re really interested in what’s going on in the field, and that’s what’s happening in cities and rural areas around air pollution.”

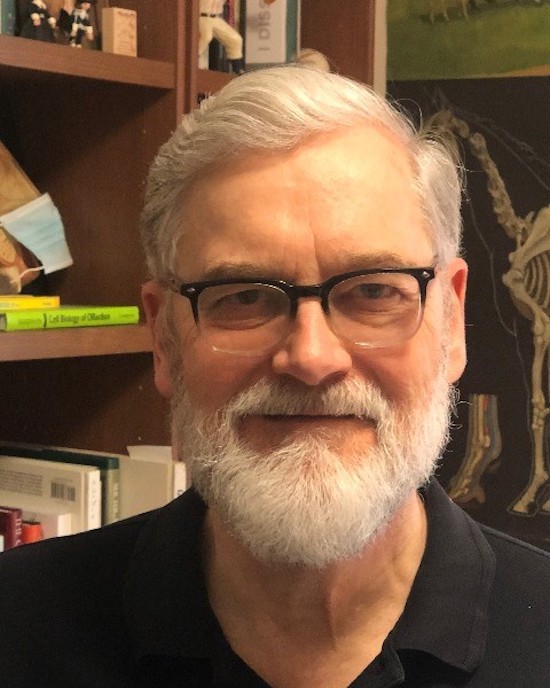

And it’s no exaggeration that Harkema, director of the Mobile Air Research Laboratories operated out of MSU, studies and experiences air pollutants firsthand. In 2009, he led the deployment of a 53-foot, 36,000-pound mobile air research laboratory dubbed “AirCARE 2” throughout southern Michigan, including the rural town of Dexter along with areas near Detroit. The mobile unit equips researchers with the ability to analyze “real world pollution in at-risk communities,” he said.

The $400,000 lab, the second of its kind (the first, AIRCARE 1, was also under the direction of Harkema), selectively pulls small particles from the air and analyzes them for chemical components responsible for damaging health effects. Through these samples, the researchers seek to discover which pollutants are the most harmful and where they come from.

“We recently brought a mobile air lab back from New Mexico on a rural Navaho reservation where we finished a study with Dr. Matthew Campen from the University of New Mexico,” he said. “With new work generated from that, we're starting collaboration with Dr. Campen and some other researchers here at MSU to look at the wildfires out West and how they have impacted the rest of the country because they generate so much smoke that travels long distances.”

With the recent alarm over the Canadian wildfires this summer, Harkema and his colleagues realize the urgency of air quality findings to inform the public. However, the mobile labs and their operation come with a hefty price tag, he said.

To read more about Harkema and his research, visit the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources website.

![The first mobile air research lab in Arizona in 2017. Captions on photo read; Michigan State University Mobile Air REsearch Lab (AirCARE1), Abandoned Uranium Mine Claim 28 [with an arrow pointing to a place in the mountains], and Navajo Hogain](https://edge.sitecorecloud.io/michigansta4044-msutodaye50e-prode5b2-fb0c/media/project/msu/msutoday/images/2023/researcher-instrumental-in-gaining-insight-into-rising-concern-over-air-pollution/aircare1aumhogan050517.jpg)