Epilogue! At the herbarium

“There’s something that’s been nagging me that makes me thinks this story isn’t quite over,” said Matt Chansler, the collection assistant at the MSU Herbarium, a few weeks after we visited him.

Matt Chansler of the Michigan State University Herbarium opened the collection to help MSUToday find answers about the Michigan State kiwi. Credit: Matt Davenport/MSU

We went partially to see how far we could retrace Sorensen’s steps, but more generally to travel back in time.

“That’s one thing these specimens let you do,” Chansler told us at the time. “Multiple people have put multiple lifetimes into this place.”

The MSU Herbarium feels a lot like a library. But rather than keeping books, it preserves knowledge in the form of leaves, stems, roots and flowers that have been carefully pressed and mounted to sheets carrying sample information: who collected it, when and from where.

For all the changes the university had seen over the past 40 years, the MSU Herbarium has been a sort of evolving constant. Its collection is ever-growing, but each specimen provides a sort of static snapshot of life at a given time, in a given spot, on an always-changing planet.

The collection provides a unique way to connect with natural and human history that so easily could be lost and forgotten. We knew the Michigan State kiwi was proof of that, but we didn’t appreciate how true that was until we went to the MSU Herbarium in person.

Chansler moved the racks to reveal the collection’s portfolio of samples from the kiwi family, or Actinidiaceae. Paging through the specimens, we saw an arctic kiwi, or Actinidia kolomikta; a golden kiwi, or Actinidia chinensis; and even an Actinidia arguta, the species that includes the Michigan State kiwi.

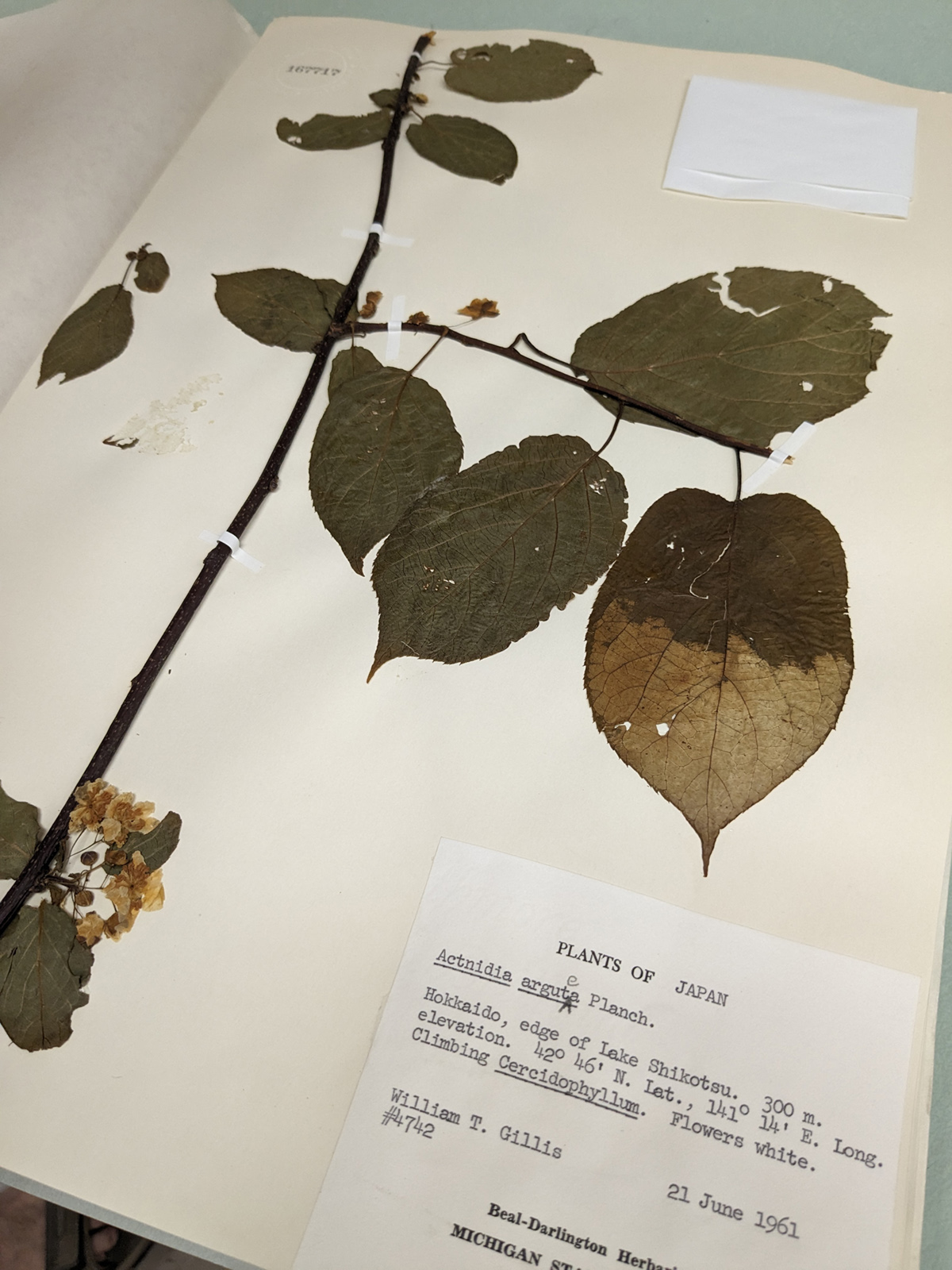

This was a different variety of the arguta, though — one native to Japan, where it was collected by Gillis in 1961 at the edge of Lake Shikotsu.

“Apparently this university had a thing for kiwis,” Chansler said.

He then took us outdoors to show us the famed window well, where he spotted two kiwi vines. One looked to be the golden kiwi we had just seen in the collection, which was likely the same one Sorensen saw and took clippings from back in the 1980s. The collection’s sample had come from the same window well decades earlier.

There are more than a dozen varieties of the species Actinidia arguta. This is one that isn’t the Michigan State kiwi but is a close genetic relative. Credit: Matt Davenport/MSU

Believing that the Michigan State kiwi was gone, it stood to reason the other vine was the arctic kiwi we had been told about at the beginning of our research, when Williams first contacted us.

But this is what had been nagging Chansler. Our untrained eyes had accepted this identification, but after our visit, Chansler kept thinking about it and thought it could be an Actinidia arguta.

He took a photo of the vine and sent it to an old friend and fellow MSU graduate, Dan Greiner. The two were also members of the Student Horticulture Association at MSU, and Chansler called Greiner the best gardener he knows.

As luck would have it, Greiner’s beautiful and acclaimed garden about 25 miles west of East Lansing in Mulliken, Michigan, is home to a Michigan State kiwi. Seeing the photo, Greiner agreed with Chansler’s assessment: The vine in the window well could be a Michigan State kiwi.

Unfortunately, the vine at MSU isn’t in the best condition for Chansler to confirm that suspicion.