In the race to make the world more livable for people and nature, progress on land is outpacing successes in the seas, raising red flags that wealthier countries’ advantages may be upsetting a balance, a Michigan State University study shows.

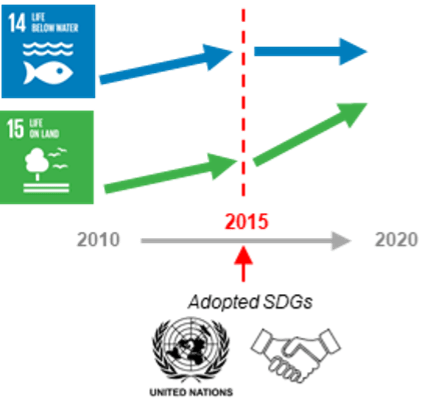

Progress in oceans slowed after the United Nations member states adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. That action aims to facilitate global partnerships among developed and developing countries in sustainable development.

So far, however, a new study in the open-access journal iScience reveals evidence that high-income countries are outpacing low-income countries, possibly slowing improvements in planetary health. Countries with accumulated wealth, privilege, special access, or inside information may succeed at a cost to less advantaged countries, causing further global inequality.

“Keeping score of sustainability is important,” said senior author Jianguo “Jack” Liu, MSU Rachel Carson Chair in Sustainability. “Making progress to maintain and improve life on Earth is a delicate balance in the telecoupled world.”

In “Global decadal assessment of life below water and on land” researchers found that conservation efforts and using natural resources sustainably had positive results on land, especially in countries with biodiversity hotspots, such as Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Indonesia.

“But surprisingly, the ocean sustainability progress slowed after 2015,” said Yuqian Zhang, lead author and a Ph.D. student in MSU’s Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability, or CSIS. “A closer look shows that low-income countries lagged, and the gap between high-income and low-income countries became wider over time. Preventing and reducing marine pollution and sharing the economic benefits that come from sustainably using marine resources with small island developing states had barely improved.”

Overall, the improvements for life on land and below waters made progress, Zhang said. From 2010 to 2020, global biodiversity conservation and sustainable development achieved positive progress both on land and sea. Sustainable use of the natural resources and the benefits reaped from them and stopping resources degradation and biodiversity loss doubled the sustainable development goal estimate in that decade.

But it’s the widening gap between the haves and have-nots of countries that causes concern and demands attention, according to the study. Specifically, well-off countries realized a tremendous increase in metrics for life below water, including Croatia, Gambia and Lithuania, while countries such as Pakistan, Fiji and Tonga experienced a major decrease in the metrics of water.

The study underscores the need for vigilance to understand global progress at a local and national level and understand why some countries are succeeding while others falter.

“We need to take a holistic look and discover the drivers for sustainability successes,” Zhang said. “This understanding can empower policymakers to design better-informed institutions for global biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.”

Yingjie Li, a former MSU-CSIS Ph.D. student now at Stanford University, joined Liu and Zhang in writing the article. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and Michigan AgBioResearch.

This story originally appeared on the Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability website.