Yasi Zamani-Hank is a graduate of Michigan State University who recently earned her doctorate in epidemiology. She is currently completing her postdoctoral research in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at MSU. Her research focuses on understanding the social determinants of racial and socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes and the role of adverse life experiences on women’s health.

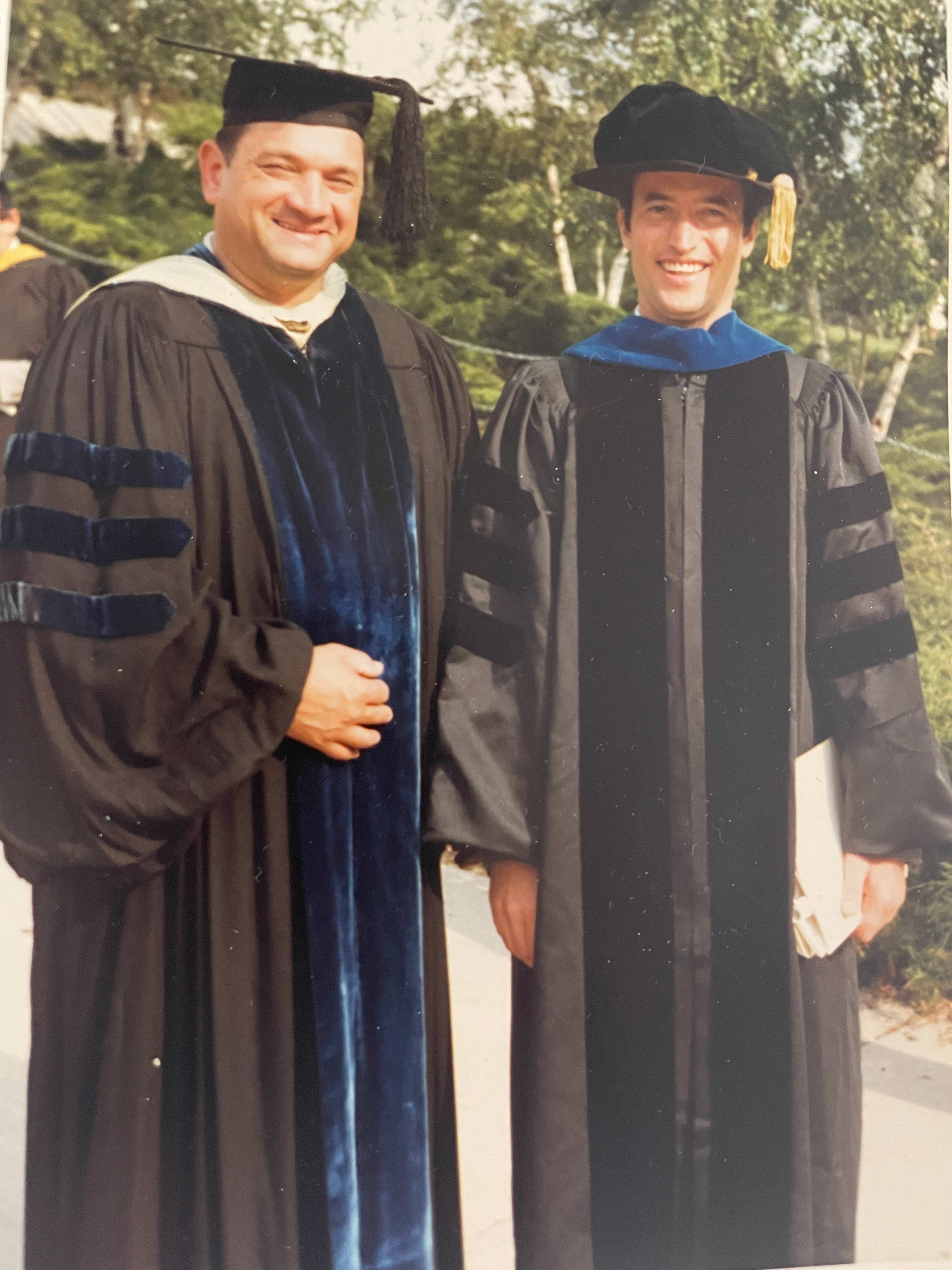

You recently graduated with your Ph.D. in epidemiology in December. The doctoral gown, cap and hood you wore has a unique Spartan family story. Can you tell us more about that?

Forty years ago, my father, an Iranian immigrant who came to the United States to pursue higher education, wore the same gown when he graduated with his Ph.D. from Michigan State University in 1982. The gown has now passed through two generations of Spartans and that holds special significance for me this year in the wake of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in Iran, which has been an emotional experience for the Iranian community over the past few months. As I reflect on how my father’s journeys as a Spartan and an Iranian immigrant have shaped my life experiences, my identities as an Iranian American, a woman, an epidemiologist and a Spartan have come full circle this year.

Can you tell us more about your father’s journey here at MSU, and how his journey influenced your life?

My father came to Michigan State University in 1976 to initiate his Ph.D. studies. Midway through his program, in 1979, Iran witnessed a political revolution that implemented a religious theocracy. At the time, many did not realize that this new government would pose such a serious threat to, and undermine, the human rights of women, ethnic and religious minorities, LGBTQIA+ individuals and political critics.

As a scientist who fervently believed in the separation of church and state and freedom of speech, my father realized he would never again be able to call Iran his home, and he became a United States citizen. The foresight of his personal life decision is something I still think about today, as it was a decision that changed the trajectory of my life.

I was born in Lansing and grew up in Okemos and East Lansing. I feel lucky that I grew up in a society where I was allowed to express my thoughts freely, wear the clothes I wanted, choose my friends and go to school where boys and girls learned and interacted together. I recognize that my life would have been very different as a young woman growing up in Iran had my father not made the decision to immigrate to the United States.

Can you elaborate on how your life would have been different if you had been a woman growing up in Iran?

Many of the freedoms we take for granted in the U.S. are illegal for women in Iran. Iranian women are not allowed to wear what they want, show their hair or sing in public, ride a bicycle or enter sports stadiums. They are denied reproductive freedoms. Iranian women are systematically excluded from public life and face daily sexual harassment and discrimination, which carries significant public health consequences for their mental and physical health. These atrocities were brought to light when Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian Kurdish woman, was killed after being arrested by the “morality” police for being “improperly” veiled. Mahsa’s death triggered nationwide and international protests which have been ongoing for nearly three months.

How have your experiences and identity as an Iranian-American woman influenced your career trajectory to pursue public health and epidemiology and your research interests in women’s health outcomes?

Ten years ago when I was applying to graduate school in public health, I wrote about my experiences traveling to Iran as a young girl in high school. I wrote about how shocked I was at the level of gender discrimination and sexual harassment that women and girls in Iran experienced on a daily basis and the effect that had on women’s physical and mental health. That foundational experience ultimately influenced my interest to study health disparities and the role of social determinants of health on women’s health outcomes. Ten years later, at the end of my formal academic training, my connection to this situation has come full circle in light of the Woman, Life, Freedom protests — reminding us that gender apartheid and gender discrimination against women in Iran remains a very real issue.

How has your training as a perinatal and social epidemiologist influenced the way you perceive the significance of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in Iran?

As a social and perinatal epidemiologist, I’m trained to think about the intricate ways in which socioeconomic, cultural, political and environmental factors interact and intersect to impact people’s health outcomes and quality of life. In fact, the slogan of the women’s rights movement in Iran — Woman, Life, Freedom, a slogan from the strong Kurdish women of Iran — is a testimony to the fact that societal factors, namely human rights, are irreversibly linked to an individual’s life, health and happiness.

In Iran, even before a girl is born, the trajectory of her life, the way she is supposed to think, act and behave is dictated by the patriarchal rule. The microaggressions that Iranian girls and women experience daily accumulate over the course of their lives, adversely impacting their physical, mental and reproductive health, which can ultimately influence the health of subsequent generations in a vicious cycle of trauma.

How have the protests impacted you personally?

Like many other Iranians and Iranian Americans living here in the U.S., I’ve been cut off from regular communication with my family members in Iran, including my elderly grandparents, due to the ongoing internet outages. It’s been very difficult.

My eyes fill with tears as I watch the news every day and see Iranian women, men, children, schoolgirls and university students of all ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, standing shoulder-to-shoulder and bravely risking their lives to fight against more than 40 years of gender apartheid and oppression. In brave acts of defiance, Iranian women are burning their veils and cutting their hair.

Over 6,000 miles away from the streets of Iran where protests occur every night, the feeling of helplessness never eases for me and my fellow Iranian Americans. We go to bed each night with a pit in our stomachs, unsure if we will wake up the next day to news of another innocent protester’s execution, another child’s death, another disappearance.

I have been working with faculty and students across the university, the Iranian Students Association, as well as local community organizations to continue to raise awareness of the women’s rights movement in Iran.

What are some common misperceptions of the situation in Iran?

A common, saddening misperception is that the lack of human rights observed in Iran has to do with Iranian culture. This is not an accurate reflection of who Iranians are and what our culture and history are about.

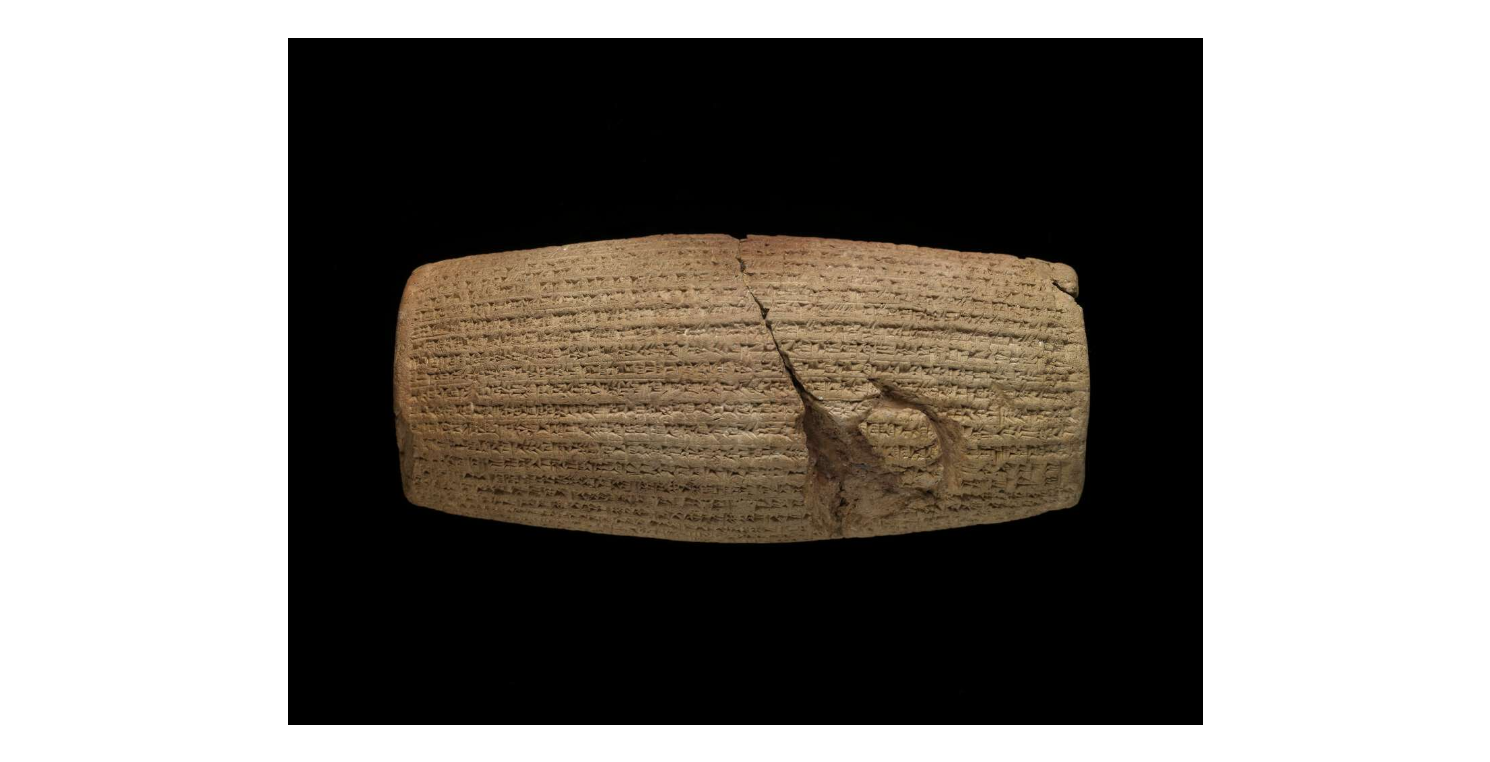

Unknown to many in the West, roughly 2,600 years ago, Cyrus the Great, a Persian king, made history as an advocate of religious freedom and tolerance. He directed the creation of the Cyrus Cylinder, a clay cylinder often regarded as one of the first charters of human rights and attributed to playing an influential role in Western political history. What Iranian women, men and children are fighting for in Iran is to reclaim their heritage as a nation that advocates for human rights, religious tolerance and freedom of speech.

Also, for those who misperceive the situation in Iran as being about religion, I want to emphasize that the movement in Iran is a nonpolitical, nonreligious and nonpartisan issue that pertains to human rights and women’s rights.

What role can MSU play in supporting Iranian students and faculty during this time?

There is a large community of Iranians and Iranian Americans at MSU, in the greater Lansing area and across Michigan who have been emotionally impacted by the situation in Iran. University students in Iran are being suspended, attacked and arrested for staging peaceful protests, and those actions need to be condemned. MSU can offer to organize listening sessions for students, reasonable accommodations as needed and connect them to supportive resources to address anxiety and mental health and, more importantly, continue to raise awareness of the situation through campus media outlets like MSUToday. Statements of solidarity are another important measure that the university can consider expressing to support the Iranian people and condemn the violence.

Many people have asked me what they can do individually as allies. It’s as simple as reaching out to fellow Iranian peers, students and faculty and checking in on them. Personally, I appreciate it when my friends and peers check in with me to express their sympathy with the situation, but I know not everyone in the Iranian community is receiving needed social support. Allies also can express their support by signing online petitions to stop the execution of Iranian protesters by going to Change.org, staying abreast of the day-to-day news on Iran from outlets such as The Guardian, sharing posts and articles on social media from Iranian journalists and activists like Masih Alinejad and attending local community-organized rallies and campus protest events, such as those organized by the Iranian Student Association.

What is one takeaway you would like people to have?

Iranian women — and the men and children who are fighting alongside them — are fighting to attain human rights and to end gender apartheid in Iran. Iranians are being punished, imprisoned, murdered, executed and raped for peaceful protesting and expressing their voices. They are fighting for basic freedoms that we are grateful to enjoy here in the United States. It’s important for those of us in the international community to be the voices of Iranians who are not being given a voice. It’s important that we continue to spread their message so the voices of Iranians are not silenced.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I want to end with something my neighbor and fellow colleague wrote recently about the situation in Iran, which I think is important to reiterate. He said, “To paraphrase a truism misattributed to Edmund Burke: ‘All it takes for bad things to happen, is for good people to say nothing.’ As generally good people, we ask our representatives to say something and publicly condemn the bad things being inflicted on so many in Iran whose well-being directly affects many in our own community.” This is an important reminder, especially for the leaders in our community and across our campus.

On Jan. 20, 5:30 p.m. at the MSU Broad Art Museum, artist and faculty Parisa Ghaderi is organizing the Woman Life Freedom evening event to raise awareness of women rights and protests in Iran.