Michigan State University and the University of California, Merced are working to get a better handle on the huge problem of climate change with the help of some very small organisms.

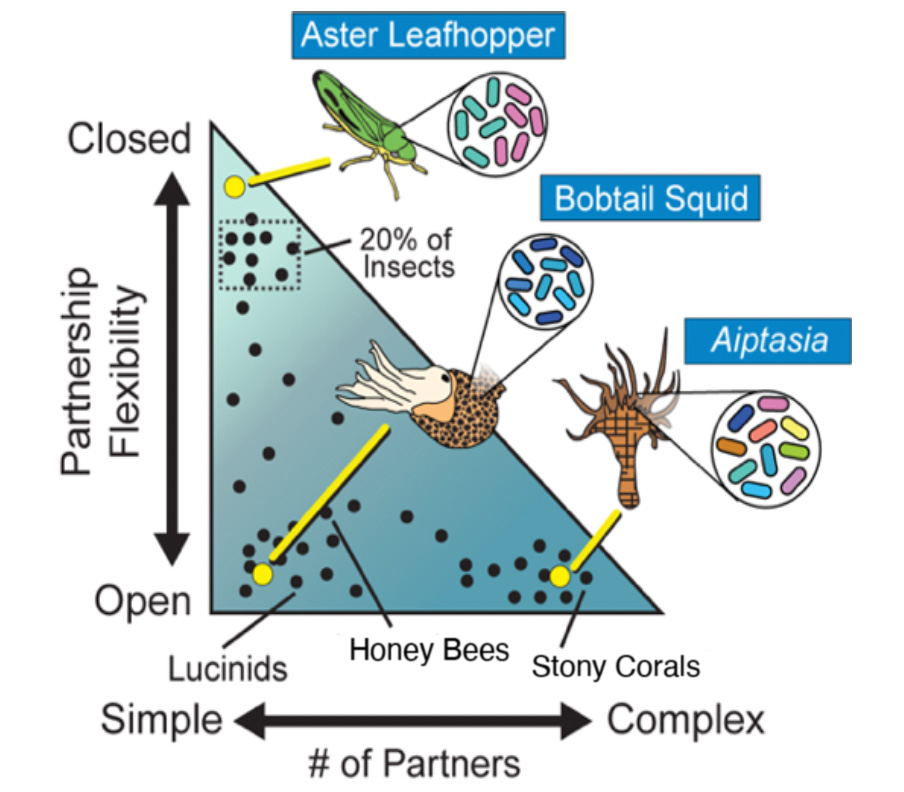

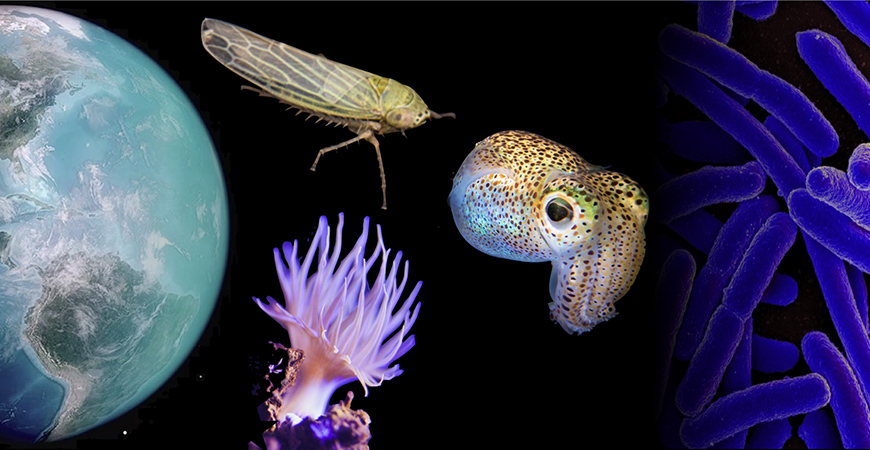

With $12.5 million from the National Science Foundation, MSU and UC Merced are launching an institute to focus on a new angle in climate change. The team will study impacts on microbes and their symbiotic relationships with host animals, including squid, insects and sea anemones. This information can better inform future climate models as well as immediate and long-term conservation strategies, the team said.

“There’s a lot of funding directed toward climate change, but everyone is looking at what you can see. We wanted to approach this problem through a microbial lens, so we proposed looking at symbiotic interactions,” said the institute’s director, Michele Nishiguchi of UC Merced. “Microbes are invisible, and they are important because they are on everything.”

“The vast majority of animal life has evolved with and in close contact with microbial life,” said MSU’s Elizabeth Heath-Heckman, a co-principal investigator for the project, which is called the Institute for Symbiotic Interactions, Training and Education, or INSITE.

“What we’re doing is getting together a lot of different experts to measure short-term and long-term effects of climate change on symbiotic systems,” said Heath-Heckman, an assistant professor in the College of Natural Science’s Department of Integrative Biology and Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics. “Then we can feed that data into models that predict climate change and get more information to the people who manage land and water to protect at-risk species.”

Nishiguchi is joined by 10 faculty members from four different departments at UC Merced. At MSU, Heath-Heckman is joined by Kevin Liu, an associate professor in the College of Engineering’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering. Two consultants are also serving on the team: one who is a conservation ecologist and another who specializes in educational research and evaluation.

“All the disciplines we have involved — biology, life sciences, computer science, math, statistics — I think that will really help push things forward,” Liu said. “The future of science is interdisciplinary.”