A study by researchers from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine is the first to establish a link between the formation of cholesterol crystals and bacterial infections in the heart.

“This was not previously known,” said George Abela, chief of the Division of Cardiology and the study’s senior author. “This is what we’ve pioneered here at Michigan State.”

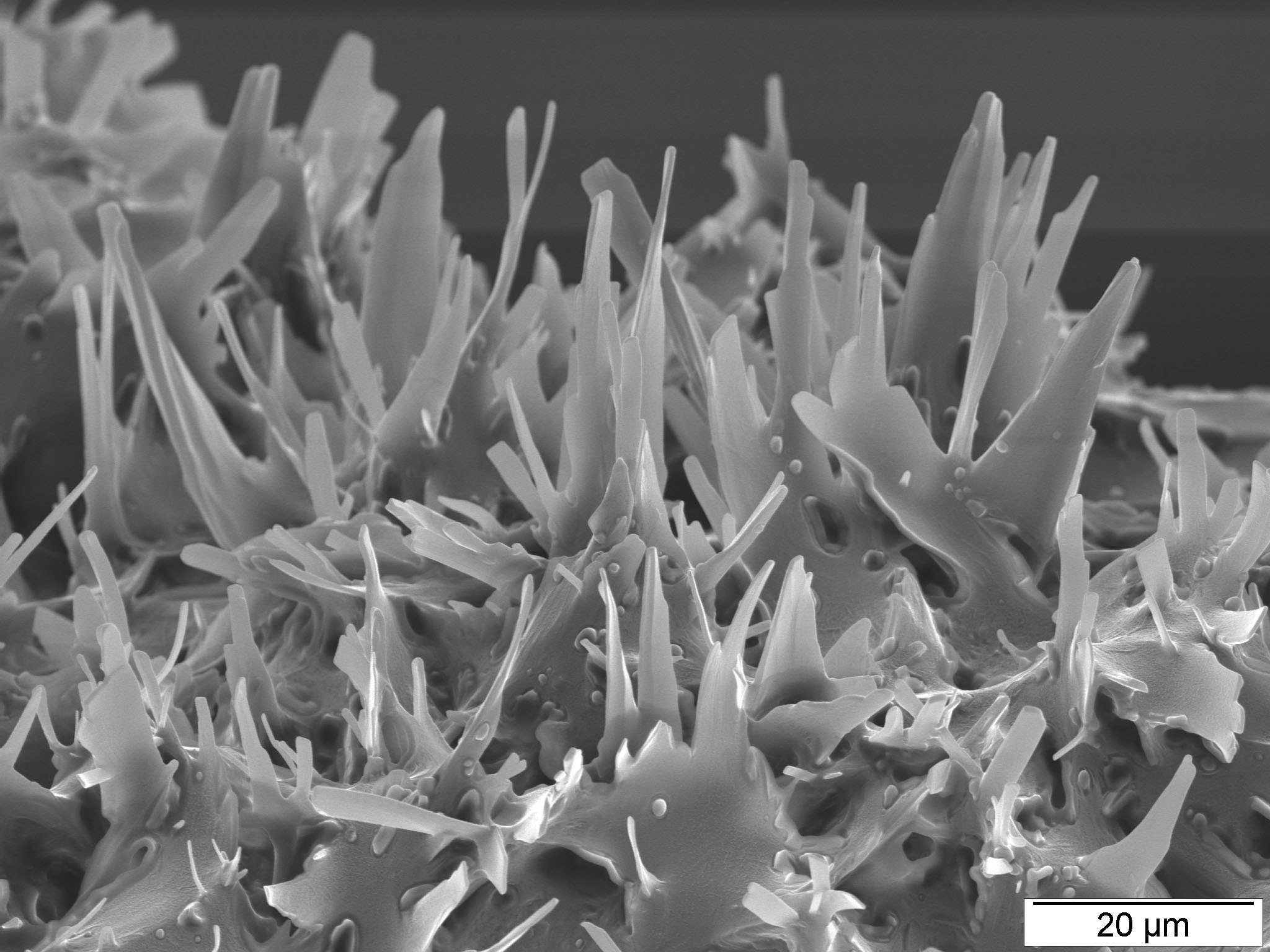

The bacteria attach and feed on the cholesterol crystals, the study found. The microscopic crystals, which are jagged, imbed in heart valves, allowing the bacteria to grow and causing endocarditis, a life-threatening inflammation of the heart valves.

“Bacteria are attracted to the crystals as a nutritional source,” Abela said. “We found the bacteria are attaching to and engorging on the crystals. That means the more crystals you have, the more bacteria are going to have a feast and grow.”

The study was published Feb. 18 in PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed, open-access scientific journal. Abela has conducted several other studies about the role of cholesterol crystals in heart attacks and infections.

A key event is when liquid cholesterol transition to crystals, which assume a greater volume in the arteries. Even a moderate drop in body temperature can trigger crystallization, Abela noted, which likely explains why many heart attacks occur early in the morning.

As the jagged crystals flow through the bloodstream, they scrape and damage blood vessel walls, causing them to spasm and constrict and possibly triggering a heart attack, he said.

The researchers found crystals protruding from heart valves, allowing bacteria to grow and infect the valves. An earlier study led by Abela found that statins could prevent the valve damage, but only if given before the onset of the disease.

Physicians often have been unable to explain exactly how bacteria stick to valves to cause endocarditis in their patients and why heart attacks sometimes follow infections, such as bacterial pneumonia.

“This study is a bridge,” Abela said. “It explains a lot of what we see on the clinical side. It helps explain why heart attacks may occur after infections, and it explains how bacteria attach to heart valves.”

“We’re working closely with other departments here on the campus to look at how this process occurs at the molecular level,” he added.

Future studies could lead to new treatments to prevent cholesterol crystals from forming. Abela referred to these as “sort of super statins,” something that has the capacity to dissolve crystals rapidly.

“This was not previously known,” said George Abela, chief of the Division of Cardiology and the study’s senior author. “This is what we’ve pioneered here at Michigan State.”

The bacteria attach and feed on the cholesterol crystals, the study found. The microscopic crystals, which are jagged, imbed in heart valves, allowing the bacteria to grow and causing endocarditis, a life-threatening inflammation of the heart valves.

“Bacteria are attracted to the crystals as a nutritional source,” Abela said. “We found the bacteria are attaching to and engorging on the crystals. That means the more crystals you have, the more bacteria are going to have a feast and grow.”

The study was published Feb. 18 in PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed, open-access scientific journal. Abela has conducted several other studies about the role of cholesterol crystals in heart attacks and infections.

A key event is when liquid cholesterol transition to crystals, which assume a greater volume in the arteries. Even a moderate drop in body temperature can trigger crystallization, Abela noted, which likely explains why many heart attacks occur early in the morning.

As the jagged crystals flow through the bloodstream, they scrape and damage blood vessel walls, causing them to spasm and constrict and possibly triggering a heart attack, he said.

The researchers found crystals protruding from heart valves, allowing bacteria to grow and infect the valves. An earlier study led by Abela found that statins could prevent the valve damage, but only if given before the onset of the disease.

Physicians often have been unable to explain exactly how bacteria stick to valves to cause endocarditis in their patients and why heart attacks sometimes follow infections, such as bacterial pneumonia.

“This study is a bridge,” Abela said. “It explains a lot of what we see on the clinical side. It helps explain why heart attacks may occur after infections, and it explains how bacteria attach to heart valves.”

“We’re working closely with other departments here on the campus to look at how this process occurs at the molecular level,” he added.

Future studies could lead to new treatments to prevent cholesterol crystals from forming. Abela referred to these as “sort of super statins,” something that has the capacity to dissolve crystals rapidly.