Saha and his team chose to work with locusts as their biological component for a few reasons. Locusts have served the scientific community as model organisms, like fruit flies, for decades. Researchers have built up a meaningful understanding of their olfactory sensors and corresponding neural circuits. And, compared with fruit flies, locusts are larger and more rugged.

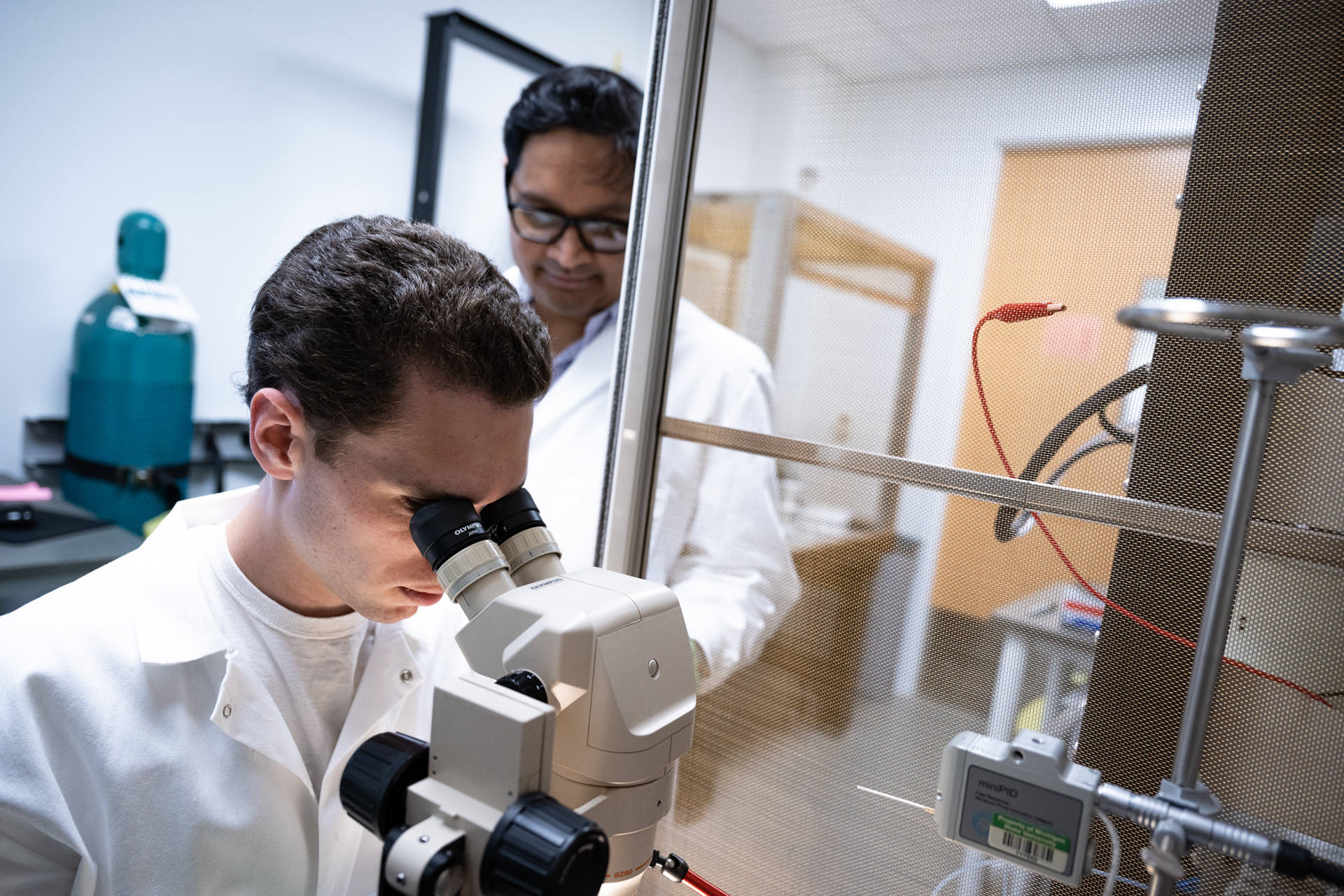

This combination of features allows the MSU researchers to relatively easily attach electrodes to locust brains. The scientists then recorded the insects’ responses to gas samples produced by healthy cells and cancer cells, and then used those signals to create chemical profiles of the different cells.

MSU Professor Christopher Contag, who is the director of the Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering.

This isn’t the first time Saha’s team has worked on something like this. In 2020, while at Washington University in St. Louis, he led research that detected explosives with locusts, work that factored into an MSU search committee recruiting Saha, said Christopher Contag, the director of IQ.

“I told him, ‘When you come here, we’ll detect cancer. I’m sure your locusts can do it,’” said Contag, the inaugural James and Kathleen Cornelius Chair, who is also a professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and in the Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics.

One of Contag’s research focuses had been understanding why cells from mouth cancers had distinct appearances under his team’s microscopes and optical tools. His lab found different metabolites in different cell lines, helping account for the optical differences. It turned out that some of those metabolites were volatile, meaning they could become airborne and sniffed out.

“The cells looked very different metabolically, and they looked different optically,” Contag said. “We thought it made a lot of sense to look at them from a volatiles perspective.”

Locusts are grasshoppers that have earned a distinct name thanks to their social, swarm-forming behavior. Credit: Derrick L. Turner

Saha’s locust sensors provided the perfect platform to test that. The two Spartan groups collaborated to investigate how well the locusts could differentiate healthy cells from cancer cells using three different oral cancer cell lines.

“We expected that the cancer cells would appear different than the normal cells,” Contag said. “But when the bugs could distinguish three different cancers from each other, that was amazing.”

Although the team’s results focused on cancers of the mouth, the researchers believe their system would work with any cancer that introduces volatile metabolites into breath, which is likely most cancer types. The team is starting a collaboration with Steven Chang, director of the Henry Ford Head and Neck Cancer program, to test its detection system with human breath.

The researchers are also interested in bringing the chemical sensing power of honeybees into the fold. The MSU team already has promising results using honeybee brains to detect volatilie lung cancer biomarkers.

Again, people need not worry about seeing swarms of insects in their physicians’ offices. The researchers’ goal is to develop a closed and portable sensor without an insect, just the biological components needed to sense and analyze volatile compounds — possibly before other, more invasive techniques can reveal the disease.

“Early detection is so important, and we should use every possible tool to get there, whether it’s engineered or provided to us by millions of years of natural selection,” Contag said. “If we’re successful, cancer will be a treatable disease.”

Other MSU contributors to the project include research associate Ehsanul Hoque Apu (who is now a research fellow at Michigan Medicine); doctoral students Michael Parnas and Alexander Farnum; undergraduate research assistant Noël Lefevre; and Elyssa Cox, the lab manager of Saha’s Bioengineering of Olfactory Sensory Systems, or BOSS, laboratory.