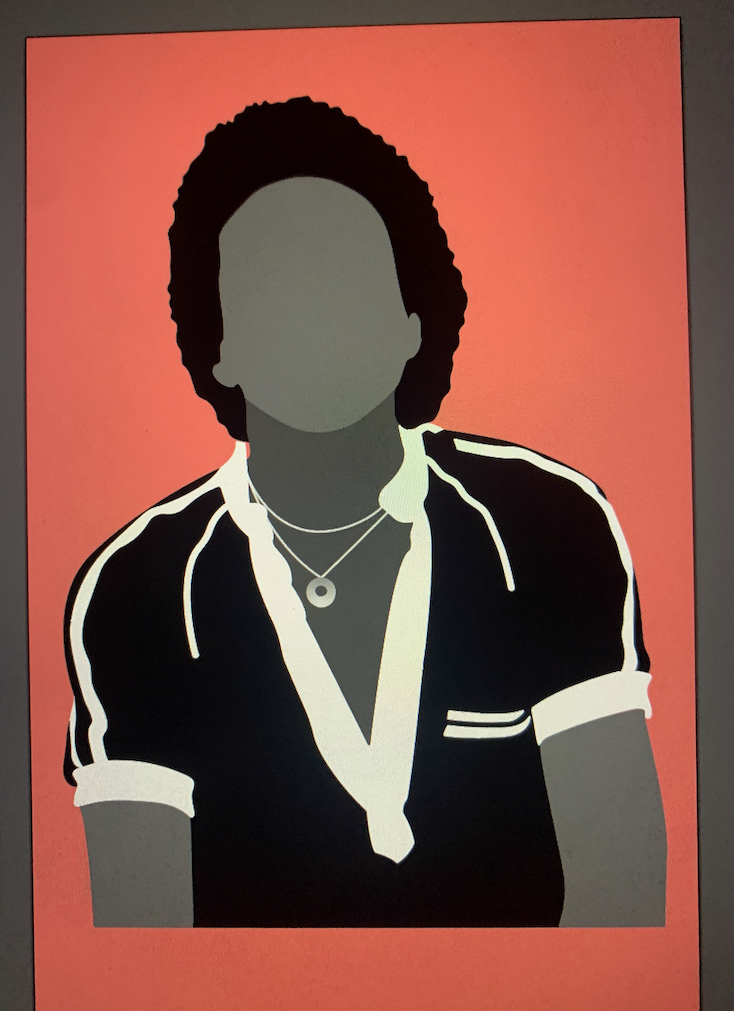

Chin was attacked by two white men, Chrysler plant supervisor Ronald Ebens and his stepson, laid-off autoworker Michael Nitz. They mistook him for Japanese, accusing him of the economic downfall of the United States auto industry.

In the 1980s, there was concern the Japanese auto industry was overtaking the U.S. and putting laborers out of work. As a result, tensions were exceptionally high in metro Detroit.

The trial of Chin’s killers was a watershed case as the first hate crime prosecution involving an Asian American. At the time, civil rights laws only applied to African Americans.

Yet, the outcome left the assailants serving no jail time with three years of probation, a $3,000 fine and an acquittal of violating Chin’s civil rights.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the murder and ensuing social movements that ultimately expanded civil rights laws to include Asian Americans and led to other tidal shifts, such as the teaching of Asian American history in higher education.

When Michigan State University professor of Asian American history and immigration policy, Anna Pegler-Gordon, arrived on campus in 2002, the university did not have an Asian American studies program.

“The brutal murder of Vincent Chin galvanized the Asian American community,” Professor Pegler-Gordon said. “Decades of advocacy by Asian American students, staff and faculty led to the founding of the Asian Pacific American Studies program in 2003-04.”

Pegler-Gordon, who teaches courses in MSU’s James Madison College and is a previous director of APA Studies, said her students wanted to document the anniversary’s importance for Michigan residents and Detroiters through an oral history project.

“It was eye opening to revisit the case at this juncture of rising anti-Asian hate,” said Pegler-Gordon. “Students were incredibly invested in the story as they realized how it impacts their lives.”

Throughout the spring semester, students conducted over 20 interviews with elders, activists, and working-class community members who lived through the case.

A student activist and project participant Justin Fernando reached out to Asian American independent filmmaker Renee Tajima Peña for an interview. Peña is the director of the 1987 documentary “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” which was nominated for the 1989 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and, in 2021, selected for preservation in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

For Peña, the film and other media coverage were a means of achieving justice. She didn’t want to paint the assailants as villains. Instead, she sought to emphasize the ordinary nature of racism.

“Ebens had a grievance like white nationalists who were out there storming the Capitol on January 6,” Peña said. “The fight for Vincent Chin is a fight against anti-Asian violence in America.”

When senior Anthony Ajluni interviewed his mother, Ellen Ha Ajluni, he discovered that his family was part of the story without realizing it beforehand. His mom played an active role in demanding justice for Chin, which made her realize Asian Americans can have a voice.

“Even though others may decide to treat me as a second citizen, I can demand to be treated as equal,” E. Ajluni said.

David Tran, a recent graduate, interviewed Sen. Stephanie Chang, the first Asian American woman to be elected to the Michigan Legislature. He learned how a community could be scapegoated for situations outside of their control.

Chang studied the landmark trial when she was in high school.

“Vincent Chin’s murder still resonates due to the rise in hate we’ve seen against the Asian American community across the country due to the coronavirus,” Chang said. “It’s really important that we’re continuing to think about what this case means.”

Chin was born on May 18, 1955. He would have turned 67 this year.

The top banner image is a photo of students in the Vincent Chin Heritage Room in Holden Hall.

Pegler-Gordon’s students are featuring excerpts from the project in a book, released during national Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Heritage Month this May. In the coming months, the interviews will be publicly available on the Humanities Commons site.