The new trigger

The idea started with a conversation Raymond and Jacobsen had back in 2019. They theorized the gas giants may have been set on their current paths because of how the primordial gas disk evaporated. That could explain how the planets spread out much earlier in the solar system’s evolution than the Nice model originally posited and perhaps even without the instability to push them there.

Sean Raymond, an astronomer at the University of Bordeaux

“We wondered whether the Nice model was really necessary to explain the solar system,” Raymond said. “We came up with the idea that the giant planets could possibly spread out by a ‘rebound’ effect as the disk dissipated, perhaps without ever going unstable.”

Raymond and Jacobsen then reached out to Liu, who pioneered this rebound effect idea through extensive simulations of gas disks and large exoplanets — planets in other solar systems — that orbit close to their stars.

“The situation in our solar system is slightly different because Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are distributed on wider orbits,” Liu said. “After a few iterations of brainstorm sessions, we became aware that the problem could be solved if the gas disk dissipated from the inside out.”

Beibei Liu, a research professor at Zhejiang University

The team found that this inside-out dissipation provided a natural trigger for the Nice model instability, Raymond said.

“We ended up strengthening the Nice model rather than destroying it,” he said. “This was a fun illustration of testing our preconceived ideas and following the results wherever they lead.”

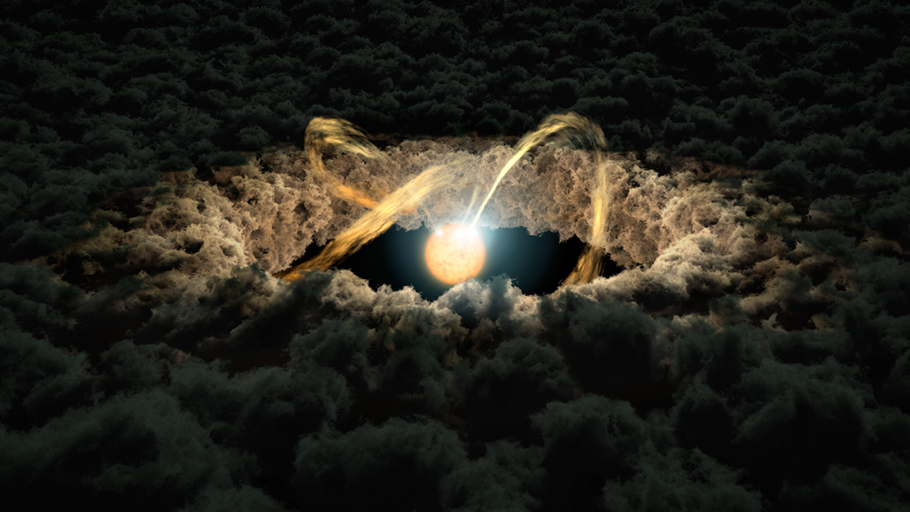

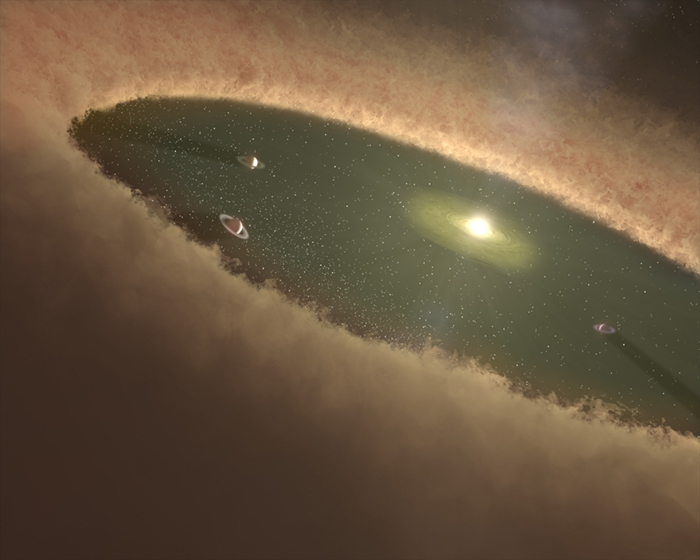

With the new trigger, the picture at the beginning of the instability looks the same. There’s still a nascent sun surrounded by a cloud of gas and dust. A handful of young gas giants revolve around the star in neat, compact orbits through that cloud.

“All solar systems are formed in a disk of gas and dust. It’s a natural byproduct of how stars form,” Jacobson said. “But as the sun turns on and starts burning its nuclear fuel, it generates sunlight, heating up the disk and eventually blowing it away from the inside out.”

This created a growing hole in the cloud of gas, centered on the sun. As the hole grew, its edge swept through each of the gas giants’ orbits. This transition leads to the requisite giant planet instability with very high probability, according to the team’s computer simulations. The process of shifting these large planets into their current orbits also moves fast compared with Nice model’s original timeline of hundreds of millions of years.

“The instability occurs early as the sun’s gaseous disk dissipated, constrained to be within a few million years to 10 million years after the birth of the solar system,” Liu said.

This animation shows the results of a simulation showing how the solar system could have been rearranged by an evaporating cloud of dust and gas. The inner edge of that cloud, shown as a vertical gray line, starts near the sun (far left) and sweeps through the orbits of Jupiter, Saturn, a hypothetical fifth gas giant, Uranus and Neptune. Credit: Courtesy of Liu et al.

The new trigger also leads to the mixing of material from the outer solar system and the inner solar system. The Earth’s geochemistry suggests that such a mixing needed to happen while our planet is still in the middle of forming.

“This process is really going to stir up the inner solar system and Earth can grow from that,” Jacobson said. “That is pretty consistent with observations.” Exploring the connection between the instability and Earth’s formation is a subject of future work for the group.

Lastly, the team’s new explanation also holds for other solar systems in our galaxy where scientists have observed gas giants orbiting their stars in configurations like what we see in our own.

“We’re just one example of a solar system in our galaxy,” Jacobson said. “What we’re showing is that the instability occurred in a different way, one that’s more universal and more consistent.”