The National Institutes of Health has awarded Michigan State University’s Morteza Mahmoudi more than $2 million to further his team’s efforts in finding effective treatments for chronic wounds.

Chronic wounds are complex injuries affecting millions worldwide that don’t heal on their own and can lead to amputation or even death. Mahmoudi said available bandaging techniques can be costly and are currently unable to overcome all of the challenges that prevent wounds from healing.

“To heal a chronic wound, you need to address all of the issues,” said Mahmoudi, an assistant professor in the College of Human Medicine and the Precision Health Program. “We’re trying to create a wound dressing that has all the features and materials needed to do that.”

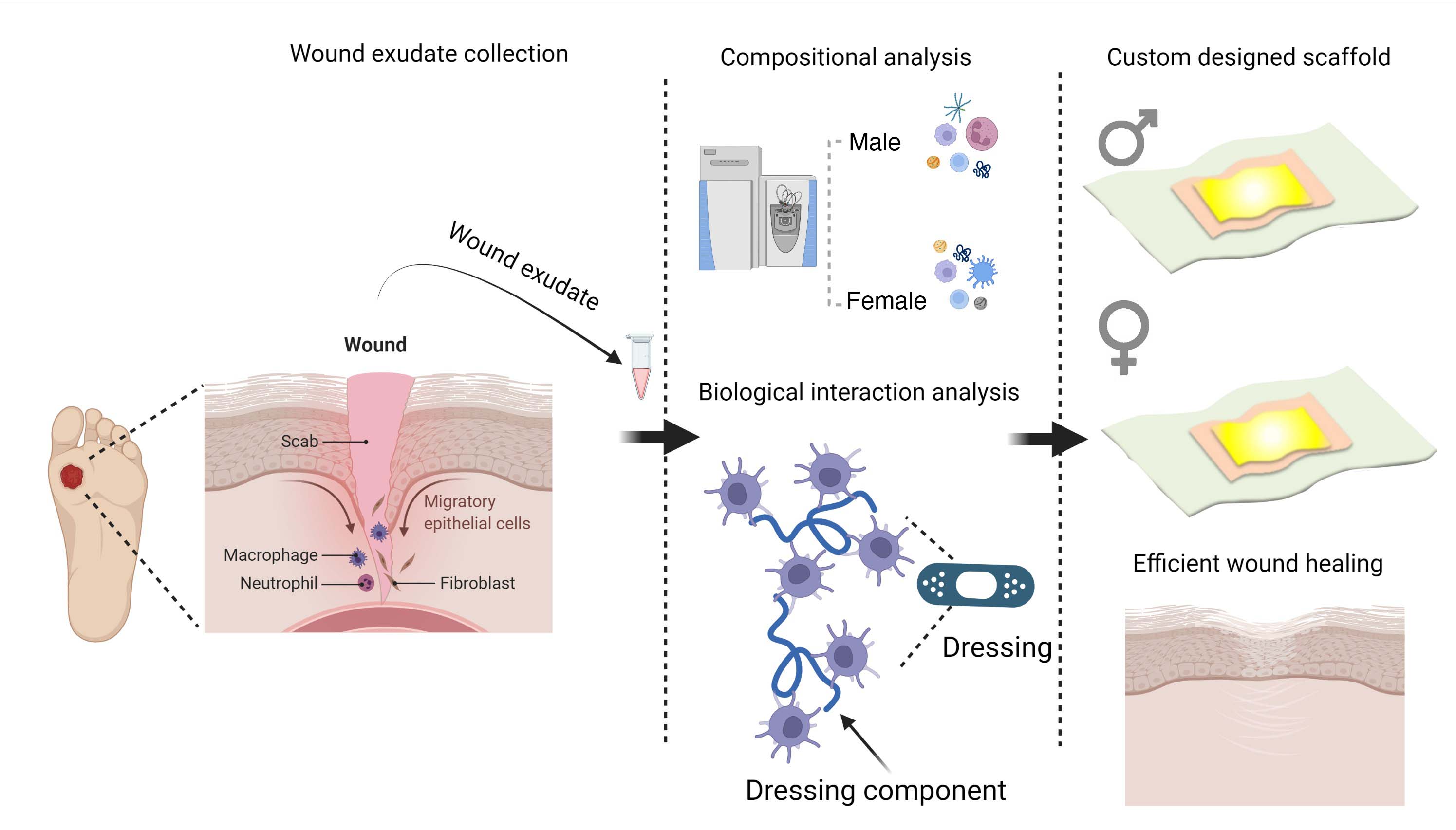

His team is designing advanced wound dressings that can confront the complexity of chronic wounds head-on. Part of the design process is refining the bandages based on how they interact with the biology of real patients.

With the new grant, awarded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Mahmoudi’s team will analyze the biological and biochemical interactions between bandage materials and chronic wound fluids. The researchers will also examine the role of a patient’s sex in the how well bandages perform and promote healing. These studies will help improve future dressings.

“For example, we think there may be significant sex differences in the interactions, so we may need to make different dressings for males and females,” Mahmoudi said.

In normal wound healing, the body can naturally repair a wound while fighting off infection. But chronic wounds are often accompanied by underlying health conditions that hinder the body’s response to injury.

Chronic wounds known as diabetic ulcers, for example, affect about 15% of patients with diabetes. Diabetes can restrict blood flow to a wound site, slowing both the natural healing process that repairs tissue and the natural immune response that fights infection. Diabetes can also lead to a loss of pain sensation near the wound that can delay the search for medical help. The longer a wound stays open unattended, the greater the risk of infection.

Mahmoudi’s team has already taken meaningful strides toward healing chronic wounds with engineered wound dressings. The proposed dressing is skin-like, flexible and designed to reduce irritation and inflammation. It also uses nanoscale scaffolding loaded with biomolecules that fight bacteria and promote healing.

The dressing is designed to help a patient’s body heal as it normally would, but each person heals differently. Mahmoudi’s next step is learning how bandages interact differently with different individuals.

With the $2 million grant, Mahmoudi’s group is teaming up with Lisa Gould from South Shore Hospital who has more than 20 years of experience as a plastic surgeon and a wound care specialist. Working with patients who have diabetic foot ulcers, the team will create a library of fluids from chronic wounds to analyze the cellular interactions with various bandage treatments.

“We want to measure all sorts of things after the interaction. How did the immune system respond? How did tissue regeneration progress?” he said. “Basically, how do our bodies perceive the wound dressing materials? How they perceive them controls how they respond to them.”

Tackling such an intricate problem requires expertise from a variety of fields — biology, materials science, mathematics and more. But Mahmoudi’s team has amassed a diverse knowledge base and network of colleagues as Mahmoudi advanced in his career.

“It’s the outcome of being a scientific nomad for a long time,” he said. “You need all these different areas to complete the puzzle at the end of the day, to solve these complex clinical problems.”

Research reported in this publication is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01DK131417. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.