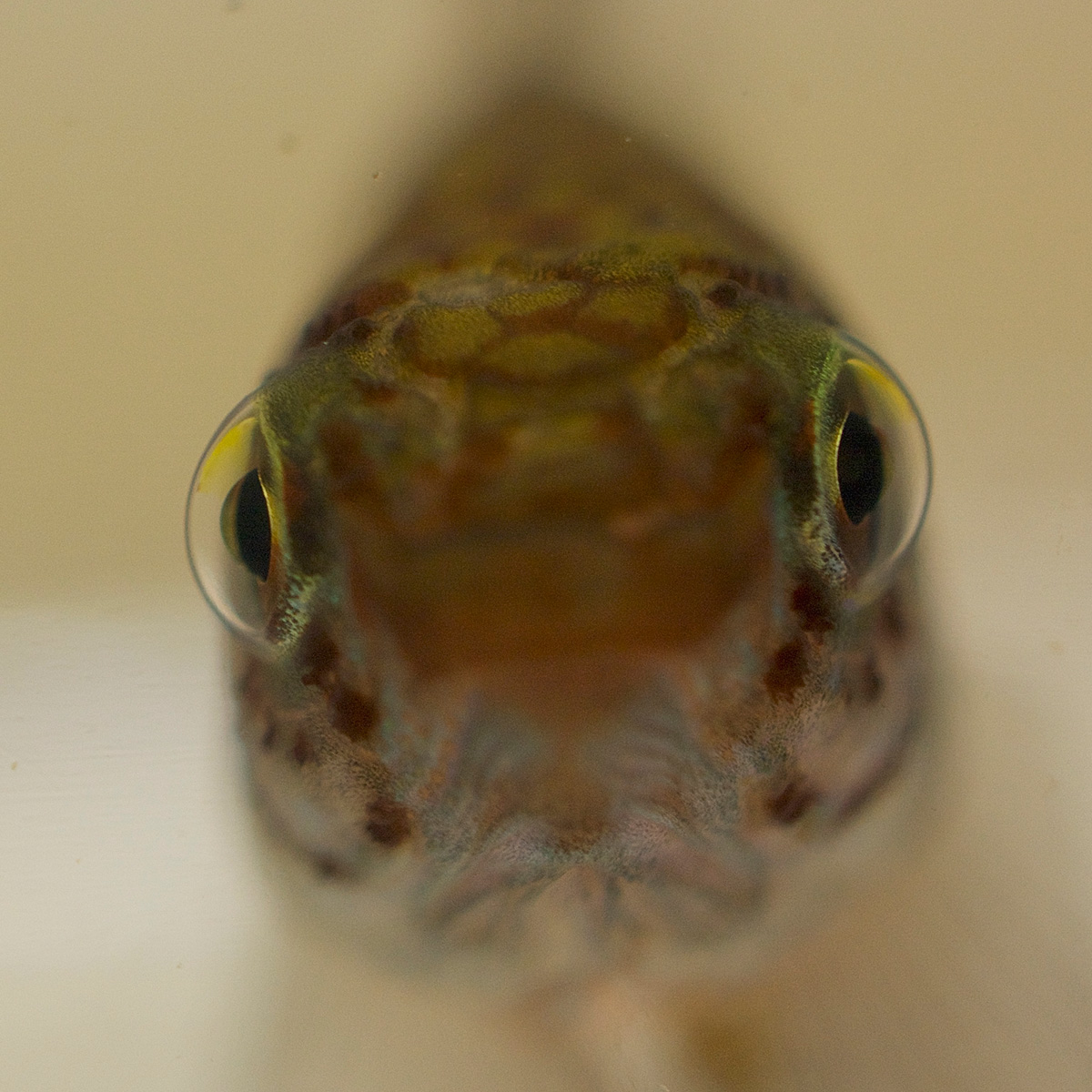

Don’t underestimate the diminutive and doe-eyed Rio pearlfish, for looks can be deceiving. This fish has evolved over the eons into one tough little customer producing eggs that can survive being completely dry for months at a time.

That’s one of the reasons Michigan State University scientists have sequenced the first complete genome of the fish. With that genome, researchers can better understand the biology and evolution of the species’ survival skills. The team also captured the full 3-D structure of the genome, which helps illuminate how and when genes turn on and interact with each other.

All of this new information strengthens the Rio pearlfish’s potential as a model organism that can further understanding of human health.

“We can learn a lot from this species,” said Andrew Thompson, the lead author of the Spartan team’s new report published Feb. 21 in the journal G3: Genes | Genomes | Genetics. “If we can understand how they control their growth and development, maybe we can understand it better in humans, too. There is a lot of potential to inform studies of human health and disease.”

This is one of the overarching goals of the Fish Evo Devo Geno Lab — shorthand for evolutionary developmental and genomic biology — led by Ingo Braasch, an assistant professor in the College of Natural Science. The group studies a variety of fish, but the Rio pearlfish has long been of particular interest to Thompson, a postdoctoral research associate on the team.

“Drew’s meticulous studies of numerous killifish species over several years revealed that the Rio pearlfish is an ideal research organism to study fundamental questions about the genetic basis of animal development and evolution,” Braasch said. “They are some of the most fascinating ‘superheroes’ of the fish world.”

Rio pearlfish are a type of fish known as annual killifish that live in puddles that form in and around Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, during the region’s two rainy seasons. Those are followed by dry seasons that run from February to March and July into August when the pools dry up and the grown pearlfish populations are wiped out. Their eggs, however, survive by essentially going dormant, entering what’s known as diapause.

“The embryos stop developing and slow their metabolism so they can wait out the dry seasons and hatch at the proper time,” Thompson said. “It’s really rare for a vertebrate to stop its development and do this suspended animation.”

Good for pearlfish, not so for humans and other large vertebrates.

“If there’s a delay in development, that’s a pathological condition for humans. It’s bad,” Thompson said. “In Rio pearlfish, it’s an adaptation.”

Examining the genetics of this adaptation could thus provide clues about what’s happening at a molecular level in human developmental disorders. On the flip side, a better understanding of the natural “hypersleep” of diapause could also help humans working to use suspended animation to make surgeries safer and extended space travel possible.

There are also other examples of how pearlfish genetics could shed light on the human condition. Because their lifecycles are so short, Rio pearlfish age quickly. In fact, scientists have already developed some other fast-maturing species of annual killifishes into model organisms to study aging. Rio pearlfish could provide another way to do so with their complete genome now available.

“We can use these fish for a lot of really cool studies in evolution, aging, suspended animation and hatching,” Thompson said. “Every vertebrate hatches, even humans.”

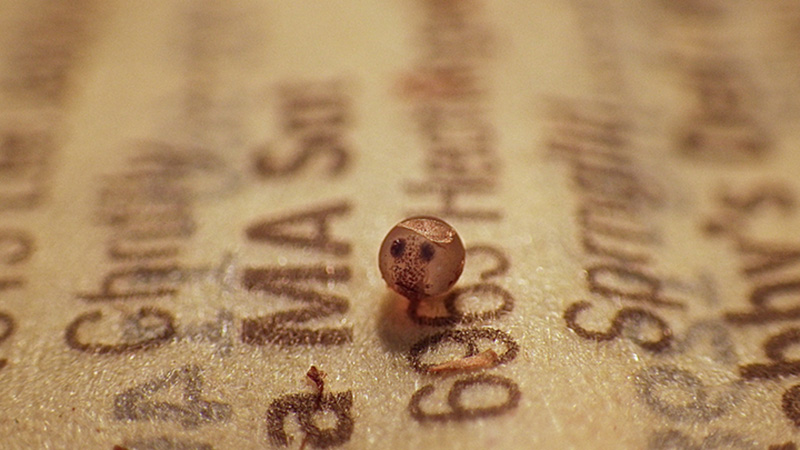

Humans, it’s true, do hatch, but very early in development. Just about a week after eggs are fertilized, embryos release enzymes to shed their egg envelopes and continue growing.

Rio pearlfish do something similar. Thanks to Thompson and undergraduate researchers Myles Davoll and Harrison Wojtas, science now know not only the genes involved in making the enzymes, but also where the gland that makes those enzymes is located. Fun fact: It’s in the pearlfish’s mouth.

“It was really great working with these two really talented undergrads,” Thompson said. Davoll was a visiting student from Clemson University who is now a graduate student at the University of Virginia. Wojtas was a Larry D. Fowler Fellow who is now an educator at the Sitka Sound Science Center in Sitka, Alaska.

“Myles and Harrison were the ones who dug into analyzing the hatching enzymes and found one of the coolest things we discovered about these fish,” Thompson said.

Although there are important differences in how humans and killifish hatch, researchers who want to learn more about early human development can now consider using Rio pearlfish as a model. And, unlike mammalian model organisms such as mice, the killifish hatch outside of the mother for all to see.

“Even if you wanted to study it in a mouse model, hatching happens internally,” Thompson said. To watch a Rio pearlfish hatch, he can just put a dormant egg in water.

The eggs’ resilience to dry conditions also offers practical advantages for establishing them as a model organism. The dried-out eggs are exceptionally hardy, making them easy to store and transport.

On the other hand, their evolutionary survival mechanism has made Rio pearlfish perfectly suited for exactly one environment under growing stress. Extended wet or dry seasons can threaten generations of fish and, as the city of Rio de Janeiro expands, the pools where these fish live vanish. This provides researchers with another important reason to raise these fish.

“They don’t live in perennial habitats and they can’t stay in diapause forever,” Thompson said. “If their habitats get bulldozed or permanently flooded, they could go extinct.”