"Ask the Expert" articles provide information and insights from MSU scientists, researchers and scholars about national and global issues, complex research and general-interest subjects based on their areas of academic expertise and study. They may feature historical information, background, research findings, or offer tips.

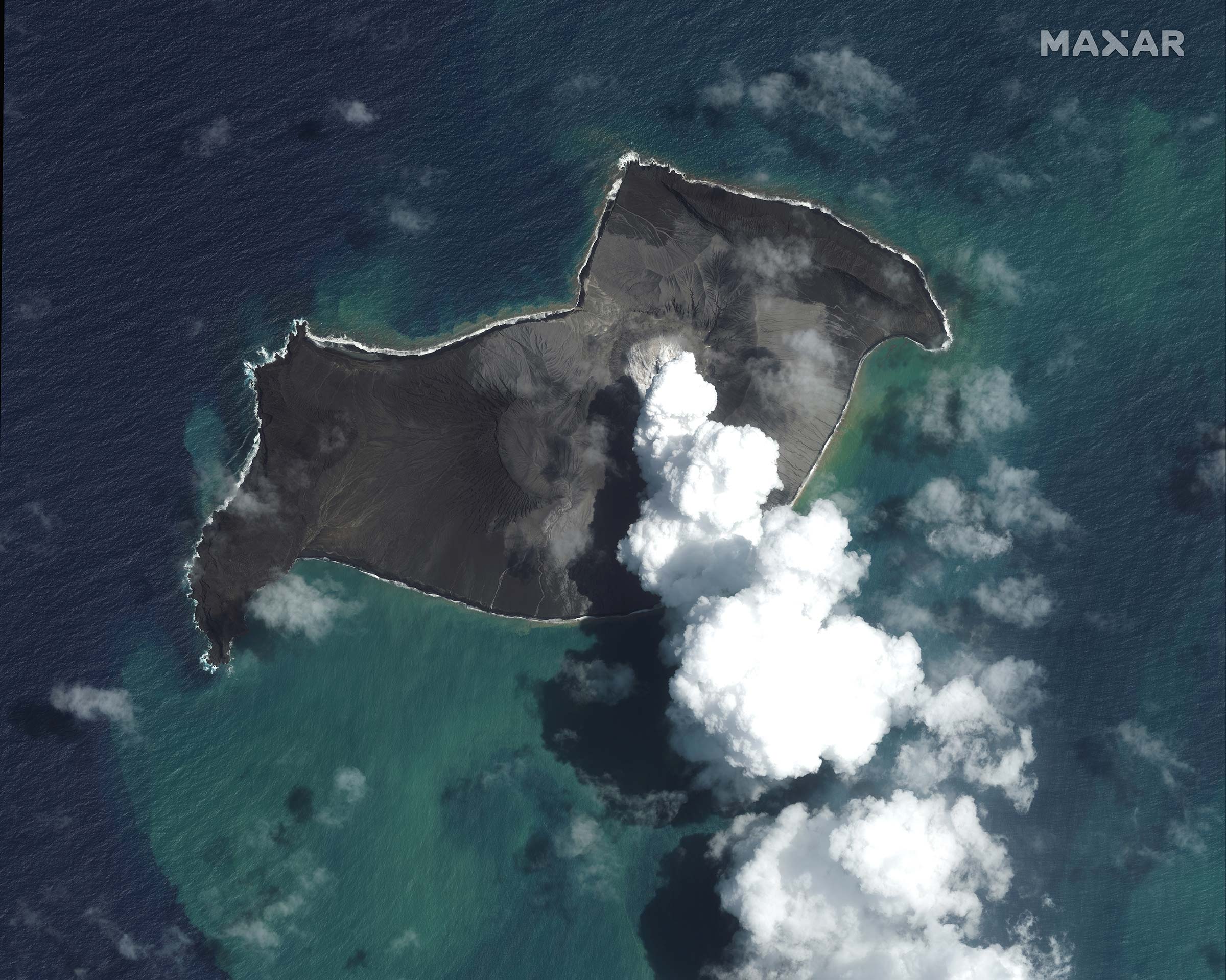

Tonga is a country that made up of more than 170 islands in the South Pacific Ocean about 1,500 miles (2,380 kilometers) from New Zealand. The Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai volcano is one of these islands. Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha'apai volcano is an underwater or submarine volcano. The volcano began erupting in December 2021, but it was the eruption on Jan. 15, 2022, that captured scientists' attention because it was probably the largest eruption event anywhere on Earth in more than 30 years.

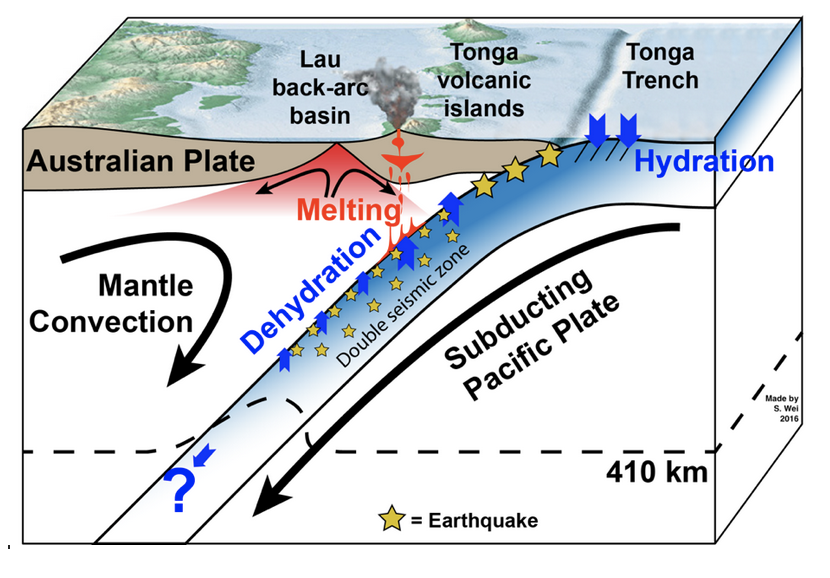

Songqiao “Shawn” Wei , an Endowed Assistant Professor of Geological Sciences in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences in the College of Natural Science at Michigan State University has been studying the Tonga region for over a decade (he is one of a small group of scientists in the U.S. focusing on this region). Wei studies the Tonga subduction zone where two tectonic plates meet and the Pacific plate slips underneath the Australian plate.

1. Why is the Tonga region unique?

Tonga is one of the most active regions in the world, with dozens of volcanoes, numerous shallow earthquakes in the oceanic trench and two-thirds of all deep earthquakes in the world. All the Tonga volcanic islands and submarine volcanoes are a part of the Tonga subduction zone. In fact, Tonga is the place where scientists (Jack Oliver and his students from Columbia University) first established the concept of a subduction zone in 1967. This was one of the key pieces of evidence supporting the newly born Theory of Plate Tectonics.

2. Was this eruption a surprise?

To be honest, this eruption is not a surprise. For a long time, we knew there was a lot of magma (molten rock) generated in the Earth’s mantle (tens of miles deep), which migrates upward to feed volcanoes on the Earth’s surface. Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai is one of the most active volcanoes in this region in recent decades.

However, the size of the eruption definitely surprised me. When Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai erupted in 2009 and 2014-2015, those eruptions were much smaller.

3. How does the eruption change your current research?

This eruption won’t change my research immediately, because I don’t expect new data to be available in the near future. But this eruption will definitely inspire my future research directions, as I’ll pay more attention to submarine volcanoes. In addition, I hope this eruption will raise awareness in the public, so that the marine geophysics community will get more support — monitoring submarine volcanoes is feasible, but costly.

Tonga is such an interesting but remote place. And the majority of the subduction zone is covered by ocean, which requires seafloor instruments that cost 10 times more than continental monitoring. So, it always takes a lot of efforts and time for us to collect data from Tonga. Unfortunately, the local Tongan scientists do not have enough resources for seafloor seismic monitoring.

We were planning to operate another seafloor observational network in northern Tonga in 2020-2022. This is an NSF funded project with MSU as the lead institution. However, because of the COVID pandemic and all travel restrictions, our project is delayed to 2023. In addition, I have other NSF projects to study this region using various seismic techniques to analyze data collected before.

Tonga is a place full of scientific surprises. I’m looking forward to new discoveries.