Regina Anderson was a junior in the College of Communication Arts and Sciences when her daughter Aria was born. When Anderson learned she was pregnant with Aria, she panicked.

Wondering whether continuing her education was even possible was added to the list of worries and fears, not to mention how Anderson would work and provide for herself and a baby. “I remember thinking to myself, how am I going to pay for child care? I was in denial and tried to conceal my pregnancy until I couldn’t hide it anymore,” Anderson said.

Anderson recalls the attention she received while she was pregnant and then as a student parent, “I can remember strolling on campus, going into one of the huge lecture halls and people staring. I had to sit at a special desk while I was pregnant, and then having to figure out where to put the stroller or having to leave the class when my daughter became fussy made me stand out.”

Despite feeling supported by her professors, Anderson felt like she was the only undergraduate parent on campus among 18-, 19- and 20-year-olds. Whether she was eating at the cafeteria, trying to study or walking down the hallway, she doesn’t remember seeing another person in her position.

Anderson, a single, African American mother, overcame significant hurdles to complete her degree as an undergraduate student parent. “I was up until 3 a.m. studying and feeding the baby. It was incredibly strenuous and tiresome,” she said.

“I think the struggle is you do everything by yourself and, when you are by yourself, it is more distressing. I wish I had known about the mental health aspect; I would have sought out therapy,” said Anderson.

Receiving help

It wasn’t until after meeting social media influencer Heather Lindsey, an MSU alumna, who recommended seeking out campus resources that Anderson found the Student Parent Resource Center, or SPRC. “It just opened up this whole window for me. They offer child care grants, supplies, events for student parents and babysitting during finals — there was an entire support group that I never heard of,” said Anderson.

According to Kimberly Steed-Page, director of the SPRC, “To me, it’s never too late to help. One of my goals is to improve how we deliver and provide access to information in ways that are most helpful to students. We need to find ways to do things differently so that students are invited to the support they need.”

There’s a cultural stigma for some students around help-seeking or utilizing resources that underrepresented student parents face that pose barriers to accessing services.

The last thing student parents are doing is slacking off or seeking special treatment. “If a student parent is on campus, it’s because they want to be there; they want to be a student,” said Olivia Kurajian, a student in the College of Law who serves as president of Student Parents on a Mission or SPOM, a student organization advised by SPRC.

Fortunately, Anderson found needed support when she connected with SPRC. “Graduation wouldn’t have been possible without the Student Parent Resource Center; I can’t even fathom how I would have made it without the resources they provided,” Anderson said.

Struggling as an international student parent

Sibbir Ahmad, an international doctoral student who is in his third year in the Department of Agriculture, Food and Resource Economics, dealt with many challenges that are common obstacles for student-parent success.

When the pandemic limited opportunities to study on campus, Ahmad’s ability to focus suffered. Living in a small apartment with his wife and child was hardly conducive to working and studying in the same space. Instead of sleeping, he pushed himself to stay awake because those were the hours when his home was quietest.

“For many of my peers, COVID was an opportunity to focus on their studies. Some would say, if COVID-19 continues for one more year, they could finish their Ph.D. online from home. So, they can prepare more and be more competitive. For me, it is challenging,” said Ahmad.

He recalls missing deadlines and struggling in taking his qualifying examination. “I felt embarrassed and had to self-advocate with my department by asking for more time to complete the final exam because I could not take the exam at home without interruptions.”

The department accepted and ended up giving all doctoral students more time to complete their examinations. Although this solved Ahmad’s immediate need, it gave other students who did not need the extension an advantage by providing even more time to work on their submissions.

With one problem remedied, another is created. “Something we need to work on is normalizing and understanding the difference between equitable support and equal,” Steed-Page said. In the interest of treating everyone fairly Steed-Page, continued, “Professors as a whole want to support student parents, but they may also feel that they are doing a special favor for one group or individual over another. You need to look at the entire situation, which involves expanding the notion of the student profile in situations like COVID.”

An equitable approach to resources is need-based and accommodates limitations impacting different parent situations. For example, international students face visa barriers that limit their ability to work and meet increased costs of accessing basic needs. In Ahmad’s case, his assistantship funding was cut in half during the fiscal tightening that many departments faced because of the pandemic, which added additional financial strain.

Furthermore, because Ahmad’s son Musab wasn’t born in the U.S., he doesn’t have access to Medicaid or government-funded public assistance. On top of that, student health care coverage only covers one dependent. Consequently, Ahmad had to choose who would receive coverage — his wife or his son.

With COVID, my wife hasn’t had insurance, so I just pray to God that everything will be fine,” said Ahmad.

While currently at MSU's College of Law, Olivia Kurajian was an international undergraduate and graduate student at her previous institution in Canada. Through this experience, she recognized the importance of health insurance for student families, especially international students.

“Health insurance for an international student is cost-prohibitive, and there needs to be protocol for what to do when a student’s dependent is ill, and the student must be absent from classes,” said Kurajian.

Finding a new home and returning to an old one

Ahmad received a lot of support from SPRC during this hard time and is now serving as vice president of SPOM. He recently moved into 1855 Place, campus housing that offers convenient amenities for families, like a grocery store, on-site parking, green spaces, a playground, and in-unit washer and dryer. “It’s a better [housing] choice for us and my family is much happier,” he said.

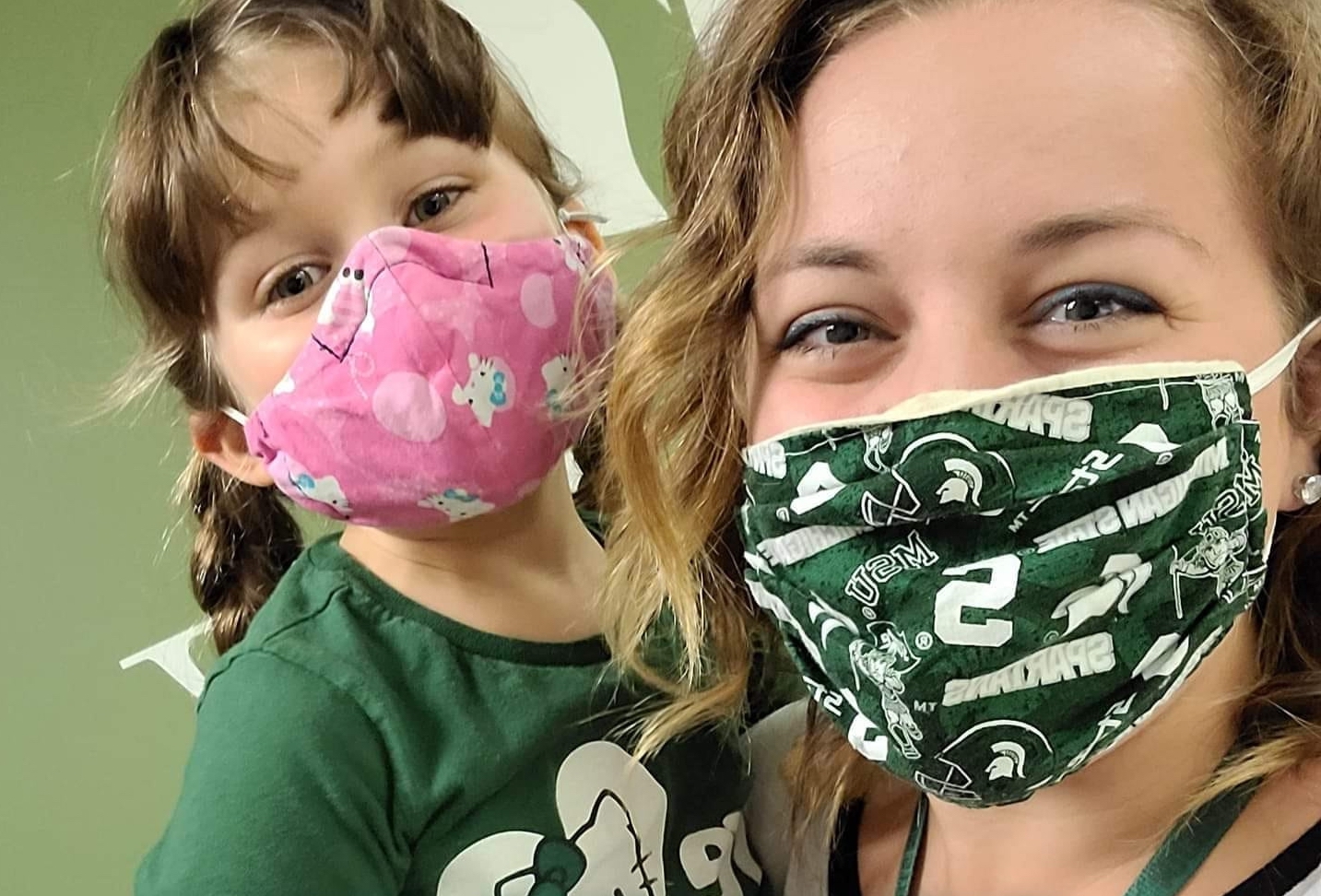

Anderson was recently accepted into MSU’s Health and Risk Communication master's program and serves as secretary of SPOM. Equipped with the information and resources to support her success, Anderson is optimistic about her choice to continue her education at her alma mater. “I love the faculty. I love the staff. I love the support, especially in the communication department and as a student parent. I know I have help here at MSU.”