Michigan State University’s Rebecca Knickmeyer is leading the largest-of-its-kind effort to understand the impact of genetics on early brain development and neurological disorders such as autism, schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Supported by a $5.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, the project seeks to illuminate which genes steer the course of brain development in both healthy and neurodivergent children. This work could help researchers develop new treatments for disorders at a much earlier stage.

“Researchers have conducted very large studies with adolescents and adults, but this will be the first time we’ve studied infants and young children at this scale,” said Knickmeyer, an associate professor in the MSU College of Human Medicine’s Department of Pediatrics and Human Development and Co-Director of the Center for Research in Autism, Intellectual and Other Neurodevelopmental Disabilities.

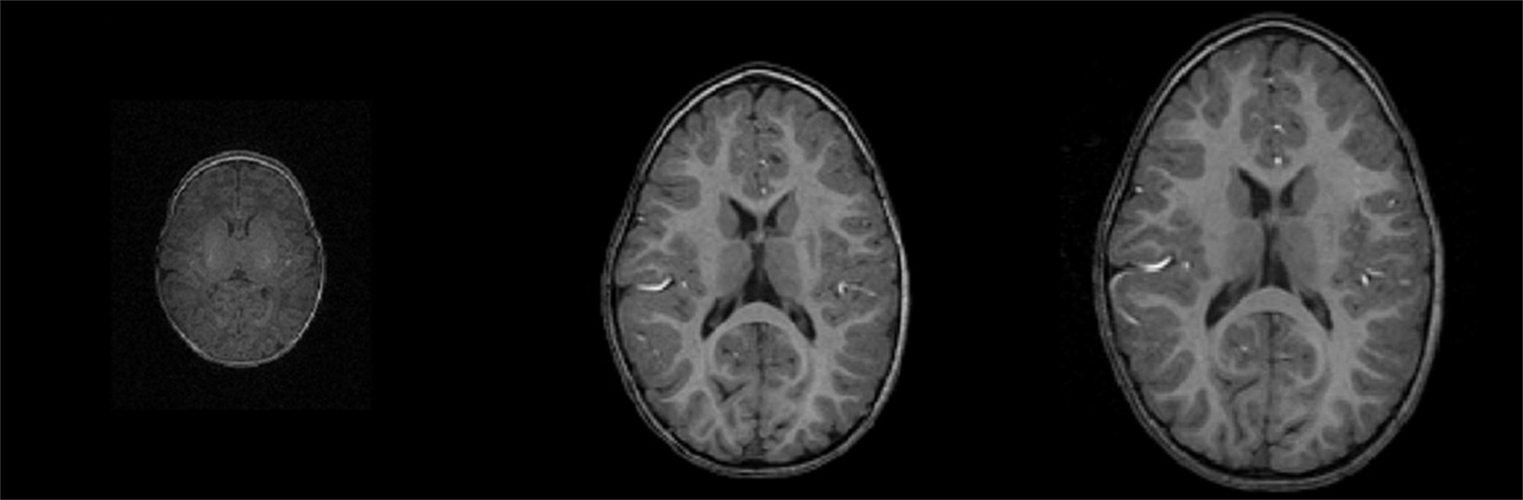

For the study, Knickmeyer and her collaborators — an extensive list of global experts from more than a dozen institutions worldwide — will assemble a cohort of 6,000 infants and young children. While studying the children’s genomes, the team will also track behavior trends and, using tools such as brain-imaging MRIs, brain development.

“When you talk about imaging studies, those are really intensive,” said Knickmeyer, who works in MSU’s Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering, or IQ. “So in the past, the sample sizes for these types of studies have been much, much smaller.”

Being able to follow so many children over several years will allow researchers to understand how differences in genetics affect brain development and the correlating impact on mental health.

“We’re going to look at variance across the genome to find which genes are driving the size, structure and function of the brain,” Knickmeyer said. “And we can look at genes that are robustly associated with autism, ADHD, schizophrenia and more to see if they’re related to what we call DIPs, developmental imaging phenotypes.”

For example, one of the phenotypes, or characteristics, researchers will be observing is the size of a child’s brain and how it grows.

“Total brain volume increases dramatically for the first two years of life and then levels off,” Knickmeyer said. “With this study, we can look at, OK, this is volume at birth, this is how big the brain gets and this is how quickly it gets there.” Connecting such information to behavior and genetics could help doctors recognize signs of disorders earlier in life and open up new opportunities for treatments.

“That’s definitely something we’re thinking about,” Knickmeyer said. “But we have to know the biology first to come up with the interventions.”

A series of MRI images shows a child’s brain developing from birth (left) to 1 year old (center) and 2 years old (right). Credit: Journal of Neuroscience

Joining Knickmeyer on the project are researchers from the Organization for Imaging Genomics in Infancy, or ORIGINs. ORIGINs is a collaboration involving scientists from across the United States — from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to the University of California, Irvine — as well as from Singapore, Germany and South Africa.

ORIGINs also belongs to a global network called ENIGMA — Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta Analysis — which is made up of more than 2,000 scientists from 45 countries studying health and disease in the human brain. ORIGINs and Knickmeyer will leverage the resources of this highly successful international group and she’ll also have help from Spartans back home. Ann Alex, a postdoctoral researcher, and Gustavo de los Campos, a professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatics, are also working on the project.

“The research questions that this project aims to answer are extremely important and exceedingly challenging,” said de los Campos, who works in the College of Human Medicine and IQ. “Rebecca Knickmeyer has assembled a very talented and highly motivated interdisciplinary, multinational and diverse group of researchers that will work with high-quality brain imaging and genetic data. I am very excited about the prospect of advancing knowledge in this important field of research.”

As is Knickmeyer.

“I know it’s not a very sophisticated way of saying it, but it feels awesome,” she said. “We have this fabulous team, this great group of minds coming together who are all interested in infants and kids. It’s really exciting to think about what we can do to support early childhood development.”