Loading component...

Julian Chambliss is a professor in the Department of English, core faculty for the Consortium for Critical Diversity in Digital Age Research and Val Berryman Curator of History for the MSU Museum.

What can comics tell us about the Black experience? As a scholar of comics and Afrofuturism, my teaching in the Department of English and my curatorial work are linked to the Black imagination. I see an opportunity to use comics to explore the intersection between speculation and liberation at the heart of Afrofuturism. On the surface, this may seem odd. The popular imagination about comics in the United States has long been defined by the assumption that comics are escapist fantasy geared toward a mostly white male audience. The reason for this is historically grounded, but this assumption ignores Black comic creators.

“Beyond the Black Panther: Visions of Afrofuturism in American Comics,” the virtual exhibit I have curated at the MSU Museum, offers a view on Afrofuturism in American comics. The choice to pursue comics to better understand Afrofuturism grows from the origins of the contemporary movement. In his definition of Afrofuturism, cultural critic Mark Dery called our attention to the fact “African-American voices have other stories to tell about culture, technology and things to come.” For us to truly understand Afrofuturism, he stressed we must seek it in “unlikely places” and “constellated from far-flung points.” Ironically, Dery’s reading of Afrofuturism relied heavily on comic books. Indeed, he says Afrofuturism “percolates” through “Black-written, Black drawn comics” produced by Milestone Media. The bold visual style and the complex world offered by Milestone was not an outlier. Instead, careful consideration of the comics produced by African American people highlights an engagement with speculation and liberation throughout the twentieth century.

“Beyond the Black Panther” offers the viewer a chance to engage with Afrofuturism's transformative message through the pages of comic books. The themes in the show — aesthetics, metaphysics, gender, science and community — are explored through a variety of comics created between 1940 and today.

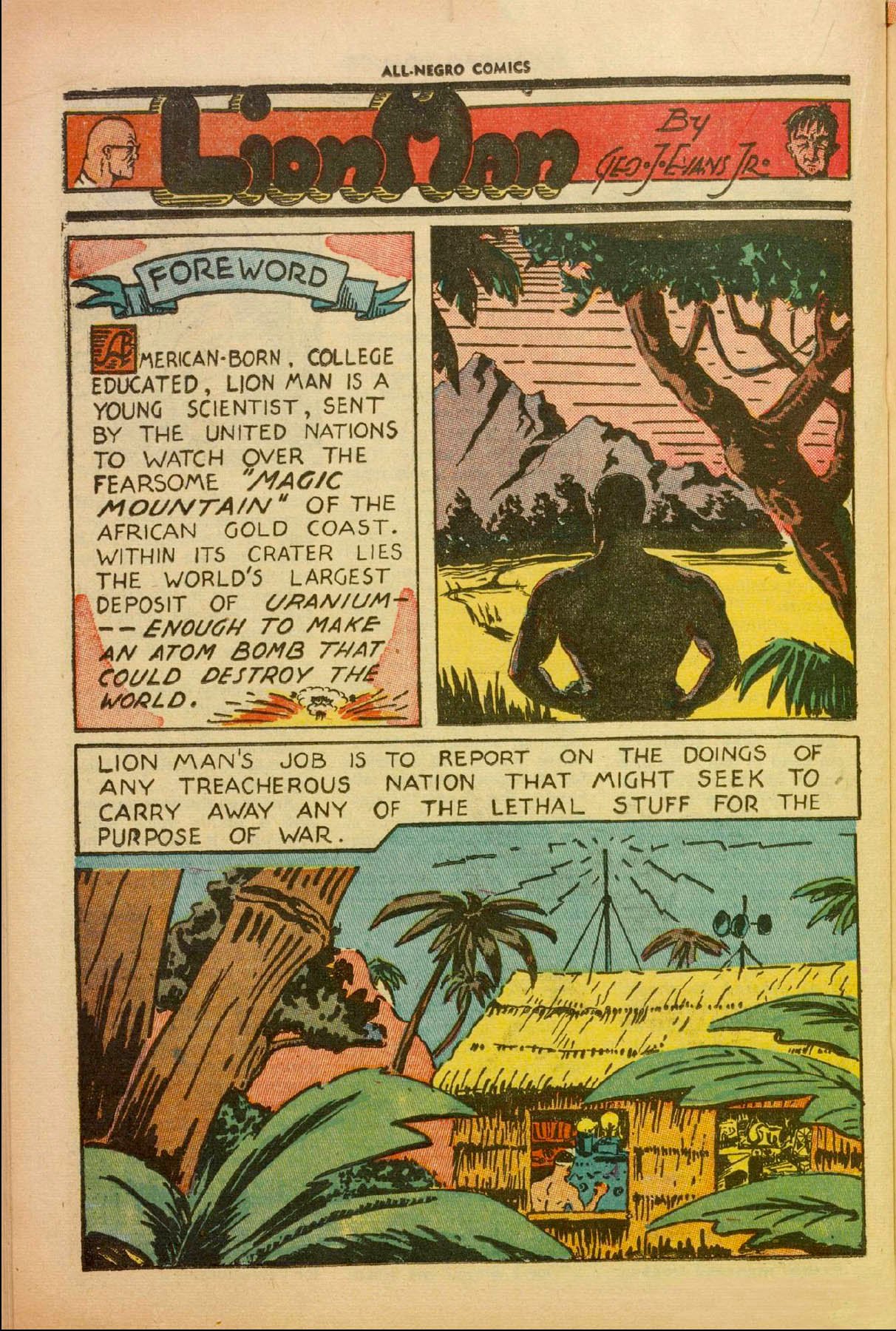

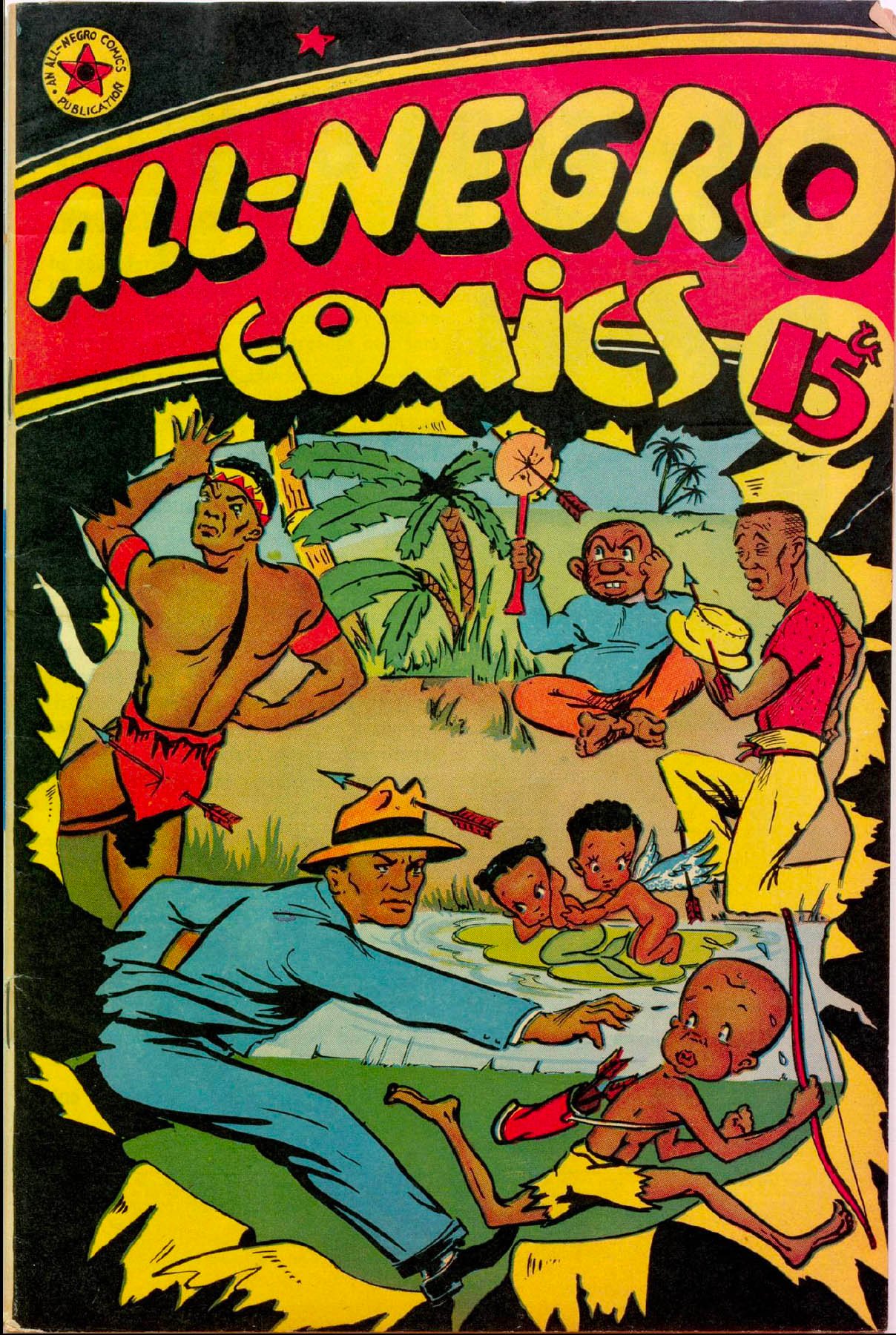

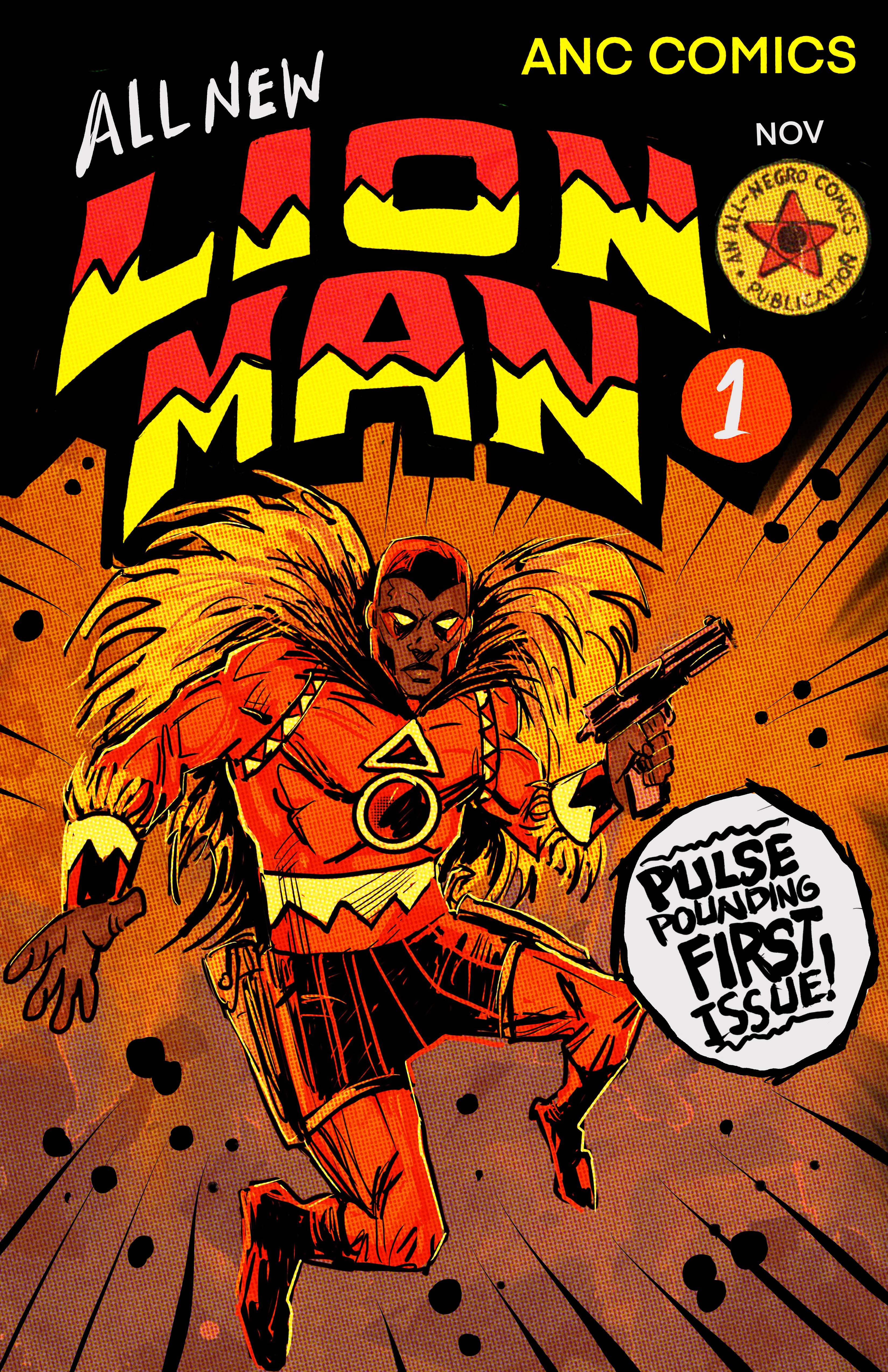

For example, Lion Man, a character first published in “All Negro Comics” #1 in 1947, is presented alongside several re-imagined versions created by John Jennings, artist and professor from the University of California, Riverside. Published in the pages of the first comic book written, drawn and published by African Americans, Lion Man serves as a protector of uranium deposit in Africa. Appointed by the United Nations, the character carries many of the tropes we attached to Black Panther today. Yet, taken in historical context, Lion Man also highlights an internationalism and fascination with innovation central to the African American vision of freedom in the 1940s.

Referenced work: Mark Dery, ed., “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose,” in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 1994), 182.