We live in a time when it’s never been easier or less expensive to sequence a plant’s complete genome. But knowing all of a plant’s genes is not the same thing as knowing what all those genes do.

Michigan State experts in plant biology and computer science plan to close that gap with the help of artificial intelligence and a new $1.4 million grant from the National Science Foundation. Ultimately, the goal is to help farmers grow crops with genes that give their plants the best chance to withstand threats such as drought and disease.

To get to that point, though, researchers still need to reveal the fundamental role of many of the genes found in plants.

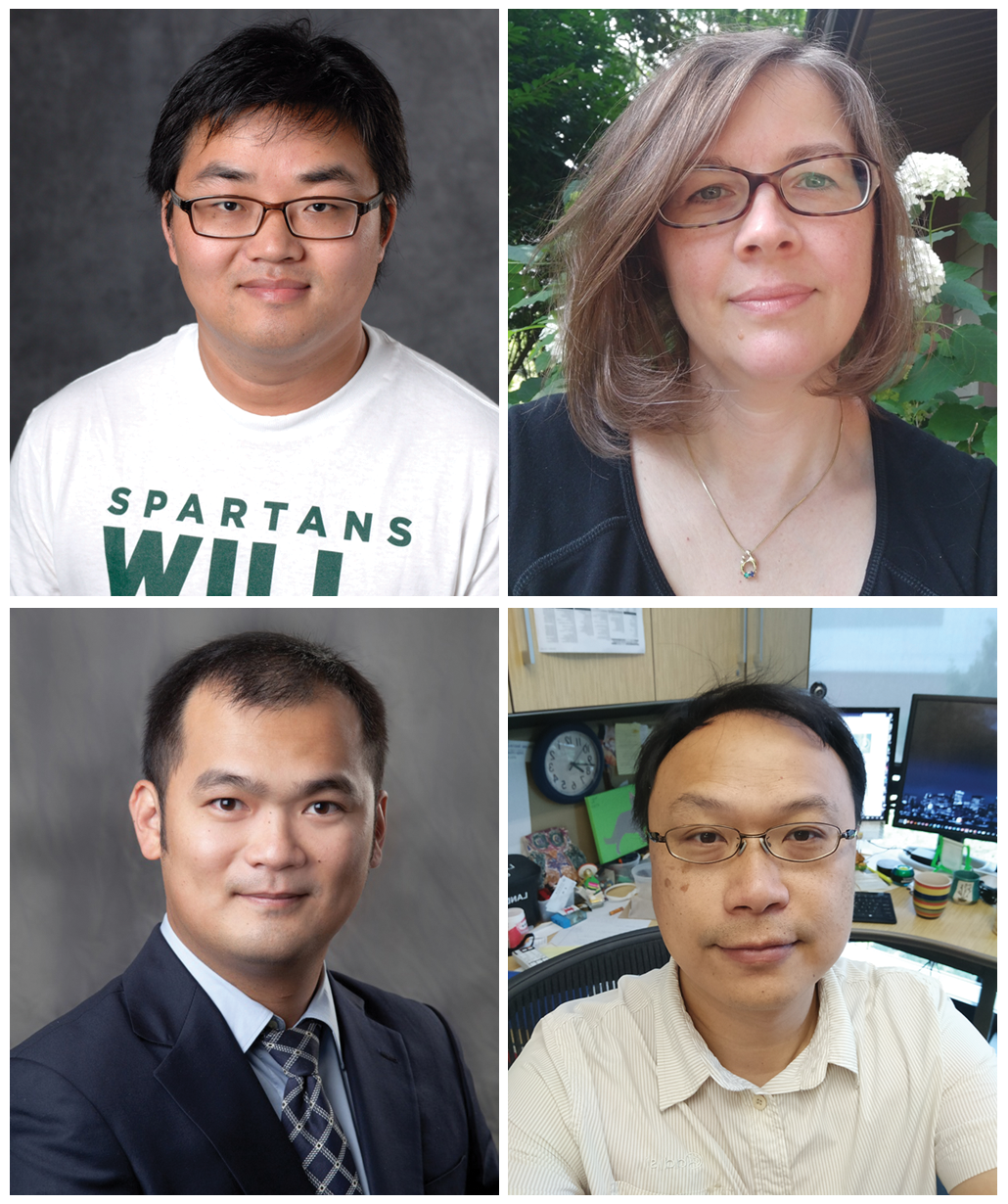

“In terms of plant science, there are major questions that we’re trying to answer: How does a particular gene sequence work? What’s its molecular function? What does it do?” said lead investigator Shin-Han Shiu. Shiu is a professor in the College of Natural Science’s Department of Plant Biology and in Computational Mathematics, Science and Engineering, a department jointly administered by the College of Natural Science and the College of Engineering.

“In the cases where we don’t know, it’s not because we haven’t tried to find out,” Shiu said. “It’s because it becomes harder and harder to find the answers through experiments.”

The Spartan team believes that AI can provide the assistance researchers need to crack those tough cases, which represent a sizable fraction of plant genes. The researchers are using a type of AI known as machine learning, which involves computer algorithms that can essentially be taught.

To “teach” the AI, the Spartans will program in available data, describing what scientists do know about plant genes and their functions. And there is a substantial bounty of this data, particularly from well-studied plants including corn, tomatoes and a model plant known as Arabidopsis.

The algorithm can then start making informed predictions about what genes with unknown functions do and then help guide scientists in designing experiments to test those predictions.

But the team is facing more than just technical challenges with this project. Some scientific communities have been particularly cautious to embrace AI and machine learning algorithms that can seem like indecipherable codes that offer up answers without context, Shiu said.

That’s why he and his colleagues knew they needed to have a group of experts from varied disciplines that could communicate effectively with each other. That way, the team could create machine learning systems where everyone could understand what the answers mean and where they came from.

“Humans need to know how the machine makes decisions, otherwise the AI is just a black box,” said co-investigator Jiliang Tang. Tang is also an associate professor in the College of Engineering’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering.

“The goal of AI is to make predictions, but we also need humans who can audit these predictions,” he said. “Our goal is to make explainable and responsible AI, which means we have to make it trustworthy and transparent.”

That’s why the team also recruited machine learning ace Yuying Xie, assistant professor in the Department of Computational Mathematics, Science and Engineering, and expert experimentalist Melissa Lehti-Shiu, a research assistant professor in the Department of Plant Biology.

“Typically, the development of a machine learning model and its applications can be disjointed,” Xie said. “By working together as a group, we have a better understanding of the methodology top to bottom. It benefits us as a group, and it pushes the science forward.”

“By understanding and interpreting the models, we can also gain insight into biological processes and why certain genes belong to certain biological pathways,” Lehti-Shiu said, adding that AI can also help focus experiments.

“Right now, it looks like there could be thousands of genes that may be important to stress responses — say, how a plant responds to heat stress,” Lehti-Shiu said. “The model can help predict which genes are the most important.”

In reaching its scientific goals — using machine learning to predict gene functions — the team is also aiming to demonstrate the power of AI as a research tool to the plant science community. As trailblazers often do, the Spartans have faced early challenges in getting others to accept their ideas.

“When I first came to MSU and became interested in machine learning, it took five years to publish our first paper using it. Plant and computer sciences have completely different cultures and use completely different languages,” Shiu said. But, working as a team, the Spartans have persevered.

“This project would not have been possible without computer scientists who were patient and willing enough to teach and work with plant scientists.”

So, although the team may be charting new territory with AI, it’s working from a proven roadmap, one that relies on teamwork and Spartans’ will. Add to that the support from the new NSF grant, and the MSU team is primed to make waves in plant science.

“I’m hopeful this will help more researchers apply AI in this field,” Tang said. “I’m excited to demonstrate its potential and promise.”