But that sense of intentional design doesn’t come from any specific feature. Rather, everything feels seamless and sensible. No space is wasted. Everything serves a purpose. Often, more than one.

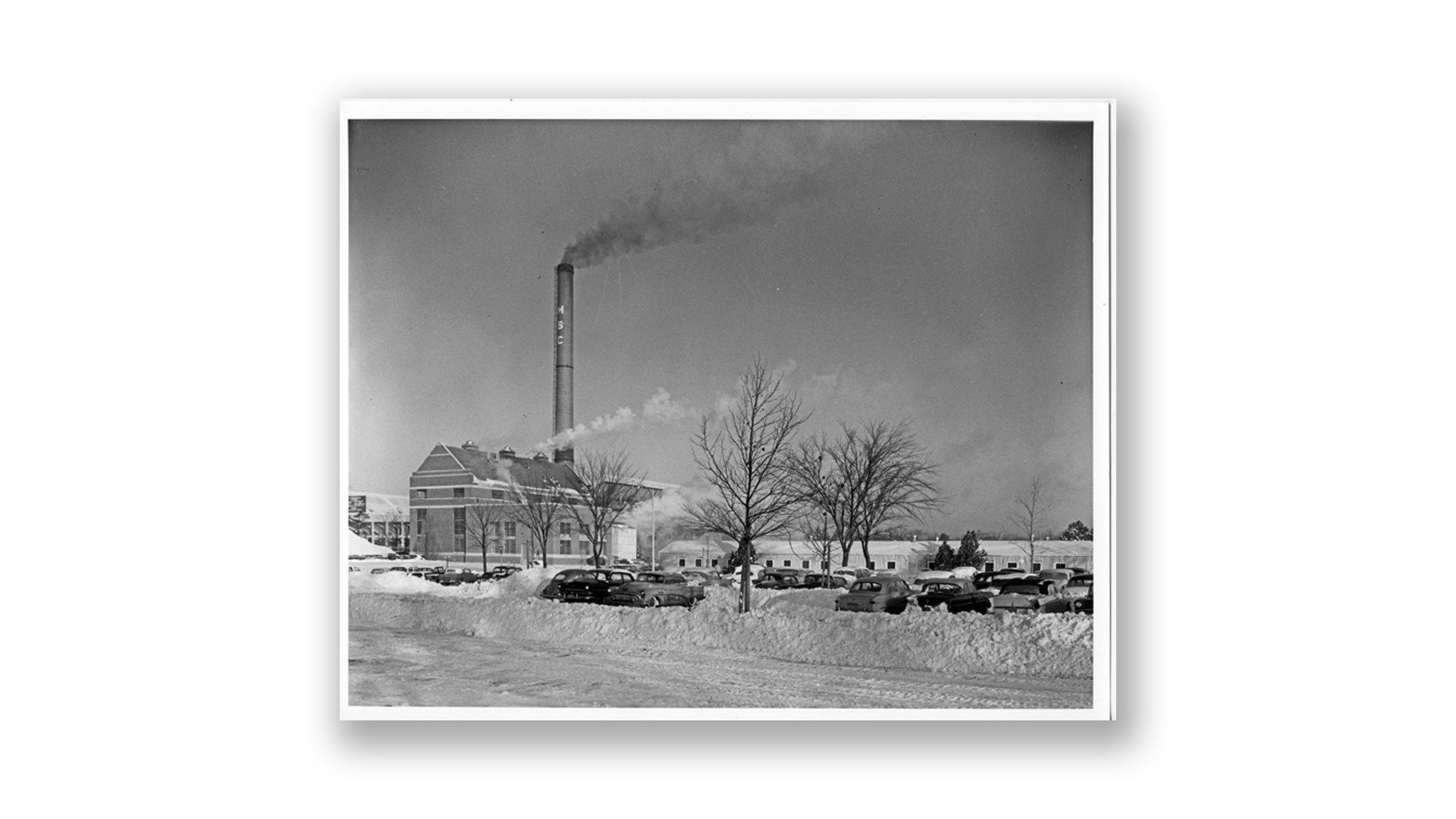

Artifacts preserved from the power plant have been transformed into seating and art installations in the new building. The power plant’s water tank remains at the top floor of the building to serve as a striking reminder of what it once was. But crews also used the tank to store water during the building’s construction.

Repurposing the power plant saved money while providing functionality. And this sustainable approach to design results in a building with an unmistakably Spartan aesthetic: warm, welcoming and ready to go to work. Bolstering both the aesthetic and sustainability factor is the building’s mass timber.

Mass timber refers to wood products used in place of more conventional construction materials, such as steel and concrete, that shoulder the loads of large buildings. Unlike steel and concrete, however, mass timber has an attractive carbon footprint. The trees that become mass timber suck carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, out of the atmosphere. Making steel and concrete, on the other hand, produces CO2.

The STEM Teaching and Learning Facility is the first of its kind in Michigan to be constructed with mass timber. No other building with combined lab and classroom space is currently built with the material.

Although the sustainability of mass timber may not be obvious to the average observer, the material itself is hard to miss. Inside the building, much of the timber is exposed, making this huge building where people share highly technical knowledge feel cozy. It’s been described “as if the building is giving you a hug.”

And this atmosphere is deliberate. The planning team worked to ensure all students feel welcome and comfortable. The giant first floor lecture hall features wide aisles to reflect modern accessibility guidelines and create more spaces where students with different mobility needs can learn comfortably. In older buildings, such accommodating spaces typically are relegated to the back of the room.

Throughout the new building, meeting spaces feature a variety of chair and table styles and heights, enabling everybody to meet in a shared space. MSU worked with Michigan furniture companies to create these accessible and inclusive spaces.

On top of that, the building’s common areas offer homey light fixtures, plenty of power outlets and ample white boards, making them spaces where students, staff and faculty would choose to meet with each other.

“We really wanted to have these comfortable, coffee-shop-like settings,” Kranz says. In fact, for anyone who enjoys coffee with their coffee-shop-like settings, there is a full-fledged café on the first floor called The Workshop, operated by Residential and Hospitality Services. It’s located steps away from the art installation housed in the power plant’s old boiler.

“This is a whole different way of thinking about how students run into each other and interact to create serendipity,” Kranz says. “We’ve built these informal/formal gathering spaces where students can just come and hang out. Or they can be used during class periods when faculty want their students to break out.”

These design principles and values are also evident in the building’s formal teaching spaces. For example, in the chem and bio labs, service lines carrying air and gas reach the students’ benches through columns mounted to the ceiling. In a more conventional lab, these lines would be built into benchtops and potentially obstruct views, especially for students farthest away from the instructor.

Using the columns opens lines of sight and possibilities by helping all students feel more connected and letting instructors more easily identify when students need help. Teachers also can work with building staff to move the columns to better fit an instructor’s needs for a class.