| 'Ask the Expert' articles provide information and insights from MSU scientists, researchers and scholars about national and global issues, complex research and general-interest subjects based on their areas of academic expertise and study. They may feature historical information, background, research findings or offer tips. |

Loading component...

"Ask the Expert" articles provide information and insights from MSU scientists, researchers and scholars about national and global issues, complex research and general-interest subjects based on their areas of academic expertise and study. They may feature historical information, background, research findings or offer tips.

Nakia Parker is the 2020-21 College of Social Science Dean’s Research Associate and, beginning August 2021, she will be an assistant professor in the Department of History. She is a historian of 19th-century U.S. slavery and African American and American Indian history.

What is Juneteenth and what did it signify in 1865?

Juneteenth is the oldest commemoration of the end of slavery in the United States — two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Specifically, June 19, 1865, is the date that the estimated 250,000 African Americans who were enslaved in Texas were told they were emancipated.

On that day, Union General Gordon Granger rode into Galveston with Union troops and read General Order No. 3. It’s unclear exactly how it was announced, but we do know the order and parts of the order were reprinted in Texas newspapers: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

The order, which was put on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., last year, also advised emancipated people to stay and work for their former enslavers for wages and noted they could not travel publicly without passes from employers.

Even though there was an official proclamation of emancipation, African Americans continued to live under restrictions to their mobility and fight for complete equality.

In what ways were newly emancipated people still controlled?

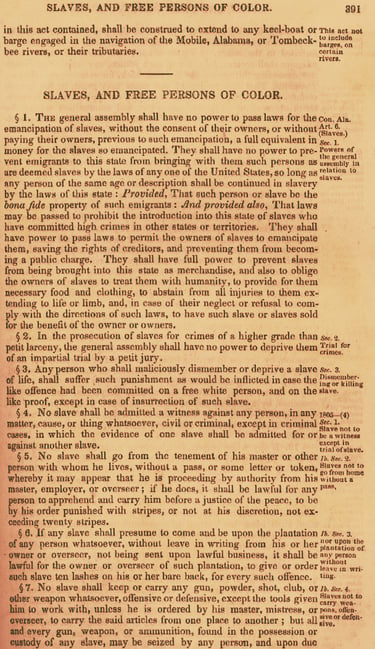

Beginning in the mid-17th century, the British colonies, which would later become U.S. states, created slave codes, rules or laws by which enslaved people had to abide. They became more specific and outlined very intentional ways to control how enslaved people could occupy space.

Black codes or laws were a way to police free Black people in the North before the Civil War. The Black codes in Ohio were infamous. Once enslaved Black people were emancipated in the South, Black codes were established there as well. For example, without a labor contract, a freed Black person could be charged with “vagrancy” and put in prison. The 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments did not drastically change conditions for Black people.

What foundational knowledge must people have to understand the history and significance of Juneteenth?

To begin, people need to understand the type of slavery practiced in the U.S. was chattel slavery. Slavery has been practiced globally for centuries, and some forms of slavery and human trafficking still exist today. But in the 19th century, Black people who were enslaved were viewed legally as chattel — moveable property.

African Americans could be bought, sold, insured, mortgaged and willed. By 1860, almost 4 million enslaved people in the U.S. were worth $3.5 billion — the largest financial asset in the U.S. economy and worth more than railroads, infrastructure and manufacturing combined. This is what we mean by chattel slavery. And yet, Black people still resisted: They formed communities, loved one another and formed a vibrant culture that is beloved and imitated worldwide.

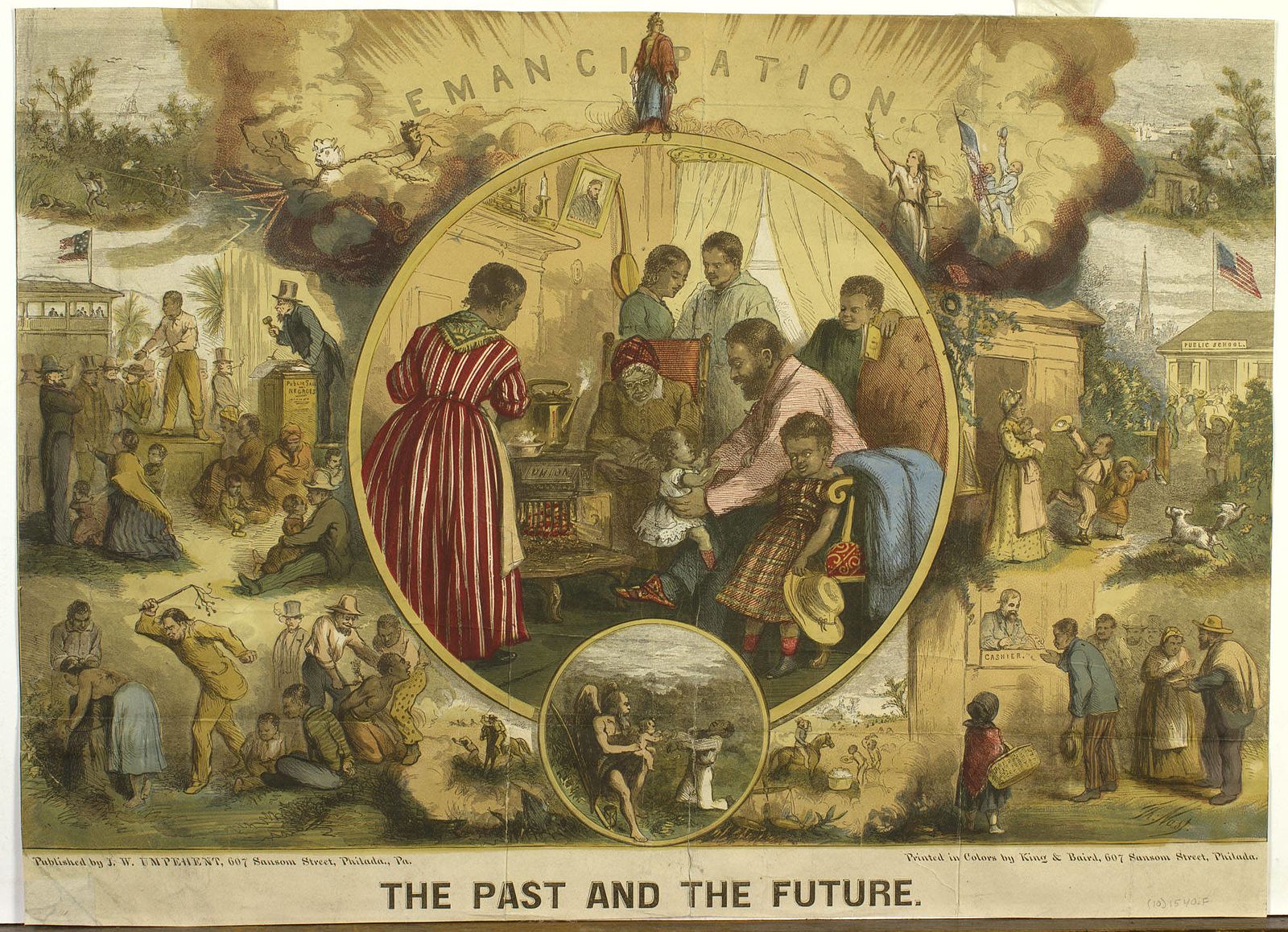

What did this new status of freedom look like for different people?

For some, that meant putting families back together — finding children who had been sold and locating spouses, sisters and brothers. People literally put ads in the newspaper to try to locate family members. Legalizing marriages also became very important because enslaved marriages weren’t legally recognized prior to emancipation.

And for some, freedom was more about economic opportunity. For example, the right to own the land people cultivated. The petitioning for land is where the saying “40 acres and a mule” comes from. When General William Sherman asked certain Black leaders in South Carolina what they needed for them to be free, the response was economic opportunity and the land they built, worked and cultivated. While that promise was never fully realized, for many Black Americans then and now, freedom in its fullest sense means having economic opportunity and building generational wealth.

Can you provide greater insight about the removal of Native people from their land and the relationship to the enslavement of African people by Native nations?

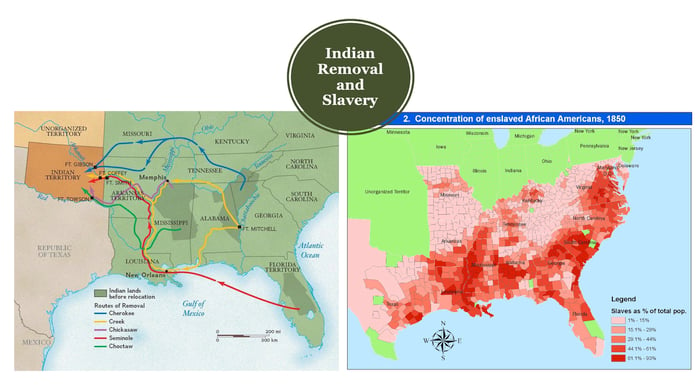

You can’t talk about Indian removal without talking about slavery, and you can’t talk about the expansion of slavery without talking about the expulsion of Native people. Historians have done a fantastic job showing the expansion of slavery in the United States, particularly in the 19th century, is due to Indian removal (a better word now being used by scholars is expulsion) of Native societies in the South.

For example, the ancestral homelands of certain Indigenous nations were in areas ideal for cotton production — Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida. Once they were expelled westward to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, cotton production and slavery in these southern states exploded.

As Native people were pushed out, they brought slaves to build and cultivate the land. Land dispossession and the violation of Native sovereignty affected the growth of chattel slavery in several ways.

As people were either forced or willfully migrated to Texas, Kansas and Missouri in search of land-owning opportunities, these places became hotbeds of controversy: Are they going to be a slave state? Or are they going to be a free state? The voluntary migrations where white people were looking for opportunities for land are wrapped in the expansion of slavery.

Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, but the part of Mexico that is now known as Texas was given an exemption and continued to enslave people. In 1836, Texas declared independence from Mexico, in large part over conflicts with Mexico about preserving slavery. Texas joined the Confederacy as a state in 1845 and, by1860, there were approximately 180,000 people enslaved. Five years later, it was almost 250,000.

In 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation stated enslaved people were to be freed, but it wasn’t until June 19, 1865, that it happened in Texas.

When we consider how the past informs the present and the theme of this year’s inaugural Juneteenth Celebration at MSU: From Freedom to Liberation, how can history help inform pursuits of liberation today?

I think we can already see how it can inform pursuits of liberation. We see discussions beginning on reparations to Black Americans for the labor performed during slavery. Universities are making efforts to acknowledge their roles in using enslaved labor; one seminary is even giving reparations to descendants of enslaved people who worked there.

We see research projects like the one here at MSU, Enslaved.org, that are working to highlight the voices of the enslaved and show events such as the Atlantic slave trade from the perspective of the enslaved. A knowledge of history, particularly the Black experience and the Black diaspora, and making it accessible is instrumental to pursuits of liberation and making the U.S. a liberatory space for Black people in concrete ways. You must know the history to think about how to reconcile it.

What do you think is an important takeaway for people learning about Juneteenth?

It’s easy to just get caught up with what affects us as individuals. We think in the present. People think about slavery as something that happened so long ago. The legacies and repercussions of slavery are still present today. We shouldn’t be apathetic about that.

It’s still here. The afterlife of slavery is still present. It shapes our social life, our political life, our economic life and our interactions with one another.

Michigan State University is celebrating Juneteenth June 14-19. For a complete list of events, visit the Office for Inclusion and Intercultural Initiatives.