Discovering beetles abroad to protect trees at home

Not every child gets a bark beetle named after them. Then again, not every kid has Michigan State University entomologists Sarah Smith and Anthony Cognato as parents.

The duo discovered two new beetle species in Southeast Asia, which they named and announced in the September issue of The Coleopterists Bulletin. (A coleopterist is someone who studies beetles). The diminutive beetle species — they’re roughly as long as a nickel is thick — are both reddish brown and dotted with little spines.

“That’s why we named one after our son, Lorenzo,” Smith said.

“He can be a little prickly,” Cognato explained.

The beetles both belong to the Acanthotomicus genus, with Lorenzo being the namesake for the newly christened Acanthotomicus enzoi. The researchers named the other new species A. diaboliculus, derived from the Latin for “little devil,” just in time for Halloween.

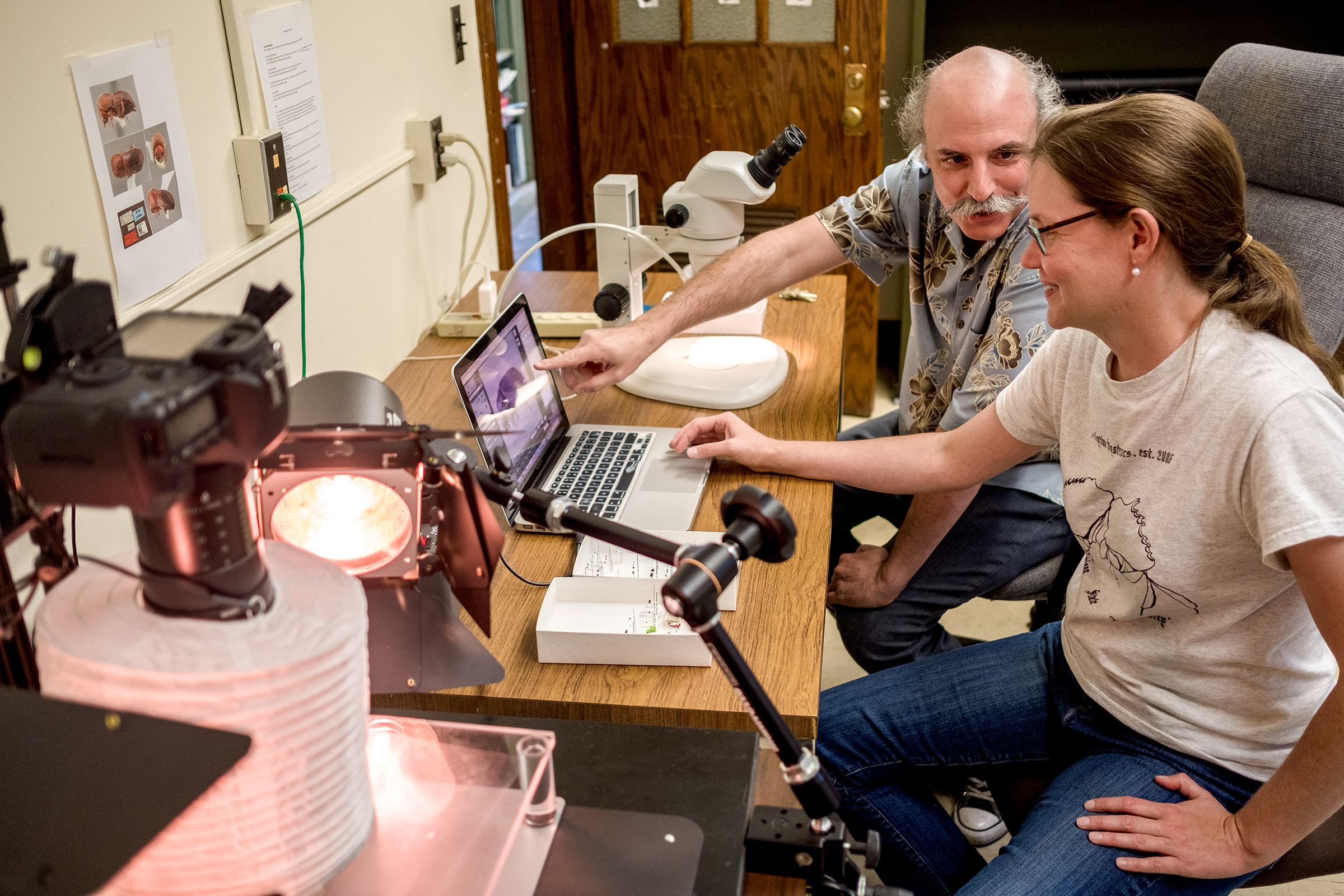

Behind these playful names, however, is a serious motivation for Smith, who is a curator in the Albert J. Cook Arthropod Research Collection and for Cognato, who is the director of the collection. Cognato is also a professor in the Department of Entomology and leads the Holistic Insect Systematics Laboratory. By identifying and studying different beetle species around the globe, in their native habitats, researchers are working to better protect the United States from species that could cause problems here.

Bark beetles bore into trees for food and shelter, Smith said. In fact, to discover bark beetles during trips to China or Thailand, for example, the team looks for the telltale sign of sawdust on fallen trees. The researchers then chip away at a tree to see what’s inside.

“Splitting wood is like opening a Christmas present,” Smith said.

After collecting beetles in the field, the researchers meticulously characterize their haul, documenting details about the insects’ appearance and genes. The team then compares its samples with all potential matches, which are scattered in collections around the globe. This step can take some time.

“For these, it took about 15 years to know that they were new,” Cognato said, referring to the two new species. “We had to rule out 96 other species.”

Another important facet of this work is understanding the behavior and habits of the new species. Many bark beetles are innocuous, setting up shop in dead, dying or injured trees, but that’s not always the case.

When beetles attack healthy trees, “that can have catastrophic implications for ecosystems,” Smith said. This can be especially true when these beetles find their way to new habitats that haven’t evolved defenses to keep the pests in check.

Although neither one of the newly discovered beetle species appears to pose such a threat to the U.S., nonnative bark beetles and related ambrosia beetles have caused problems on American soil before.

For example, the redbay ambrosia beetle found its way from Asia to the state of Georgia in the early 2000s, likely stowed away in wooden packaging materials. Now, the beetle has made its home in nine states, bringing with it a fungus that has all but destroyed coastal redbay laurels and has started attacking other trees, too.

“It’s decimated avocado trees in the Southeast,” Cognato said. There are looming concerns the beetle will spread to larger avocado operations in California, Mexico and South America.

This may remind Michiganders of the nonnative emerald ash borer, or EAB, whose beetle babies have killed tens of millions of ash trees in Michigan since 2002. The EAB belongs to a different family of beetle than what Smith and Cognato have discovered, but it underscores the importance of this type of work. By discovering and documenting beetles in their native habitats, researchers in the U.S. can better prepare for and possibly predict the next invasive species.

To that end, Smith and Cognato are preparing to publish a book detailing 315 ambrosia beetle species found in Southeast Asia, 63 of which are new to science. They’ve also created an online database to help others rapidly ID these beetles.

Beyond the protective aspects of this work, beetle biodiversity remains a huge mystery, Smith and Cognato added. Scientists have discovered just a fraction of beetle species worldwide and within this small piece, researchers have revealed myriad appearances and behaviors.

“Biodiversity in general is amazing and relatively unknown,” Cognato said. “It’s worth the time and effort to try and discover new species.”

Acanthotomicus enzoi and A. diaboliculus are the latest additions to the list of discoveries made by Smith and Cognato, which contains well over 100 species and counting.

That said, the two new species do present one element of completion. Now all three children in Smith and Cognato’s household have beetles named after them.