Loading component...

When a special cat named Sophie arrived at Michigan State University Small Animal Clinic with a rare knee condition, the MSU veterinarians got creative and used a first-of-its-kind surgery to get her back on her feet.

Both of Sophie’s stifles (knees) suffered from medial patellar luxation – or, when a kneecap dislocates or moves out of its normal location toward the inside of the limb. She also suffered rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament (the feline equivalent of the anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, in people) on the right.

“Sophie’s owners first noticed that she was lame in her hind legs four months before we saw her, when they found her unable to jump up onto the back of the couch and up onto their bed,” said Karen Perry, BVM&S, MRCVS, DECVS, associate professor in small animal orthopedics at the MSU College of Veterinary Medicine and veterinarian for the MSU Veterinary Medical Center’s Orthopedic Surgery Service. “Her owners noted that occasionally she would bunny hop and that she appeared to be very stiff in the hind limbs when she got up from laying for a long time.”

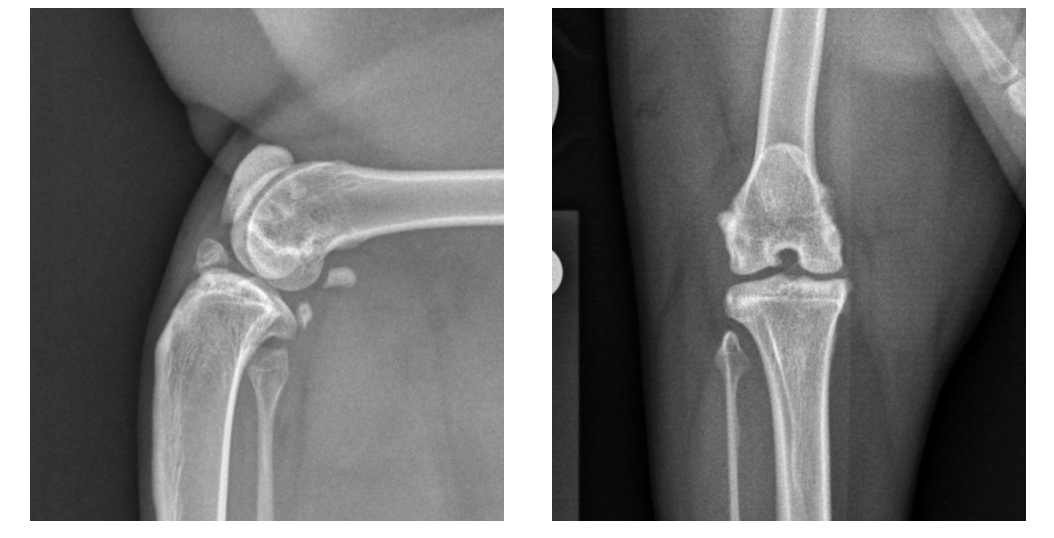

Perry’s team conducted an orthopedic examination and collected X-rays to properly diagnose Sophie. They found that her right patella would intermittently luxate, or dislocate, toward the inside of the limb. Additionally, there was instability in the right stifle, with the tibia (shin bone) being able to move forward relative to the femur (thigh bone) when the limb was weight-bearing. This instability indicated that her cranial cruciate ligament was ruptured. Patellar luxation also was evident affecting her left stifle, but her cranial cruciate ligament was intact on that side.

Sophie’s final diagnosis was bilateral medial patellar luxation and concomitant right cranial cruciate ligament rupture – similar to a dislocated kneecap and torn ACL in a human, Perry explained. “

The combination of Sophie’s injuries is very uncommon in cats, and there is very little information about how to treat it,” Perry said. “Sophie’s patellar luxations were considered very unlikely to resolve or improve substantially without surgical treatment. Additionally, while some cats with cranial cruciate ligament rupture do improve clinically with non-surgical management, this improvement does take a long time and is often incomplete with stifle instability remaining.”

Therefore, the veterinary team recommended Sophie have surgery on the right side for both conditions, which her owners were open to. There also was a possibility that Sophie would require surgery on the left side in the future.

While surgery was considered the most efficient route to a full recovery, exactly which surgery was the question.

After contemplating common procedures available, the MSU Orthopedic Surgery team considered an alternative technique, the tibial tuberosity transposition and advancement – or TTTA – which has shown superior clinical outcomes with fewer associated complications in dogs with similar injuries.

“To our knowledge, no one had thought to use TTTA in cats,” Perry said. “But because Sophie’s specific injuries were complex and this technique has been shown to be beneficial in dogs, our Orthopedic Surgery team decided to adapt the TTTA technique for use in Sophie.”

A TTTA surgery changes the biomechanics of the knee. The surgeon cuts into the tibia and alters the relative position of the two bone sections to create a 90-degree angle between the tibial plateau (the top of the tibia) and the straight patellar ligament, which inserts on the front of the tibia. This renders the stifle intrinsically stable, such that the function of the cranial cruciate ligament becomes redundant. It also treats the patellar luxation as the relative positions of the two pieces of bone can also be altered in another plane simultaneously to straighten the quadriceps mechanism. When the quadriceps mechanism is straight, there is no tendency for the patella to luxate. Minor adjustments to the technique and implants used in dogs were necessary to facilitate application in a cat, but Perry considered the surgery a success.

Sophie recovered well from anesthesia and was comfortably able to bear weight through her operated limb in less than 24 hours. Upon discharge, Sophie’s owners received strict instructions for incision care, activity limitations, physical rehabilitation, diet alterations and recheck appointments. For full recovery, Sophie needed strict exercise restriction to avoid complications such as implant breakage and slow bone healing.

“In the absence of any previous reports of this procedure being performed in cats, we could not entirely predict how quickly Sophie would recover. However, eight weeks post-op, her lameness improved rapidly with only a very mild and intermittent limp and her bone healed well with no complications,” Perry said. “Additionally, at follow-up exam, the instability previously noted affecting the right stifle had resolved and the patella could not be luxated.”

At present, six months post-operatively, Sophie is reported to be doing very well. She traveled south to Florida with her owners, where she enjoys long walks in her stroller and sunbathing.