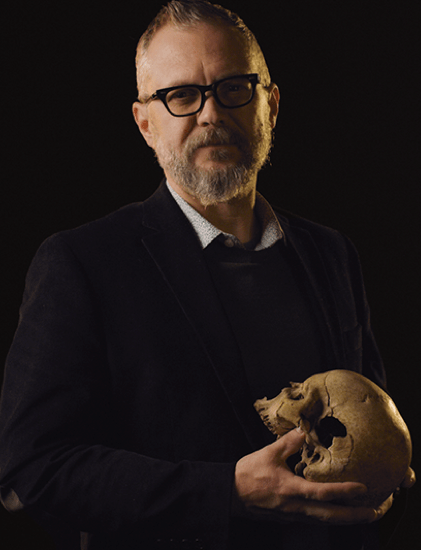

In the classroom, Joe Hefner leads one of only six forensic anthropology doctoral programs in the nation. In the lab, he has developed new ways for researchers around the world to identify and classify human skeletal remains. In the field and at crime scenes, he and his team use their expertise to help unravel complex crime scenes — from homicides to Ground Zero following 9/11.

Hefner and his colleague, Todd Fenton, chairperson of the anthropology department, are the only board-certified forensic anthropologists in the state of Michigan and two of just 130 in the United States.

On the scene of a crime, Hefner is often called upon by police departments at a moment’s notice to travel to a crime scene and examine a body before it goes to a medical examiner’s office. He says he treats crime scenes as archeological sites while he looks inch by inch to gather evidence and information that will later be applied to his skeletal examination.

He approaches every scene wanting to answer two questions: “Who is it?” and “What happened?”

Every fragment of every bone in a skeleton is a piece to the complex puzzles that Hefner has made a career of solving. Everything from bone density to skull shape plays a part in how he and the team at MSU piece together the story behind the crime.

Hefner uses x-rays to find tiny fractures or anomalies to compare against medical records, intricate dental exams to find cavities or abnormalities that he can compare to dental records, as well as forensic genealogy to narrow down potential identifications. By looking at a skull, he can even determine ancestry based on slight variations in shape.